‘I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to my mother Peggy Hurst who told me much about my family and even after his death talked so much about my father Gordon. Although I remember Gordon as a person in my very young life, I was alas too young to really know him and to be able to recognise and then to value his wonderful qualities. Peggy had met him while training to be a nurse at University College Hospital in Gower Street, London. He was one of her patients. When they started to go out together to concerts and plays and walks in London parks, this was pretty daring – nurses were not supposed to form relationships with their patients. They married and Gordon practised law and they went on honeymoon to Switzerland. Not long after I was born we embarked on World War II and life became quite difficult. I remember watching doodlebugs – flying bombs – flying overhead and huge waves of bombers filled the sky. I remember the sound of air raid warnings and the all-clear – in fact, the sound is quite vivid even now. I remember the Anderson shelter – a big bunker in the garden. The Morrison Shelter was really our dining table with a steel sheet on top which we all used to sleep under at night in case the Germans dropped a bomb. One night a bomb dropped nearby and blew our French doors into the garden and there was glass everywhere. I was too young to be frightened.

I remember Lyme Regis best of all – my grandparents’ home. Hole Cottage was paradise and where I spent most of my childhood because it was safer to be down there. Sometimes Peggy and Gordon were able to be there too. I played in the fields and helped on the farm down the road. I remember haymaking with horses and carts with the Hallets. I remember the rabbits running out in front of the scythes and the cart. The horses were huge shire horses. I remember the American soldiers who were all over Dorset as they prepared for D Day. They had jeeps and used to give me chocolate.

My grandfather (Grampy) kept chickens which ran wild everywhere and I was once attacked by the cockerel which frightened me. Hole Cottage was the former gamekeeper’s cottage on the Woodroffe estate. Old man Woodroffe was very good to Granny and Grampy. Hole Cottage was very primitive – no electricity or running water. Water came from a well in the garden and I can remember the excitement when a tap was installed in the wood – but we still had to carry the pails into the house. The loo was the Ivy House in the garden. The place was always full of creepy crawlies and I didn’t like staying there very long. I used to have a bath in an old hip bath in front of the fire in the drawing-room. Every evening oil lamps were lit and we went to bed early, the whole house creaked and I was often frightened in the dark. Aunt Nancy said she once saw a ghost at the cottage – a man hanging from a beam in the barn. Apparently a man did hang himself there in years gone by but she had a vivid imagination and she may not have seen it. I never did, fortunately! Every evening a lovely white barn owl would come swooping down the drive as regular as clockwork and roost in the barn.

I was once accused by Granny of telling a fib about something. I immediately dived under the dining table and said, “God, aren’t I telling the truth?” Then in a deep voice, I replied “Of course you are telling the truth Anthony”. Resurfacing I said, “There you are.” Everyone assumed that odd expression when trying to look serious but wanting to laugh. It was a really idyllic childhood and my heart will always be in Lyme. I was totally safe and free from danger. Everyone was kind to children, no-one put pesticides in fields and everything was green and sunny.

Of course, there was a world war going on and countless people were suffering terribly but I was too young to know all this. I remember long train journeys in the blackout when the train would stop for hours in the middle of nowhere while an air raid was going on. I clearly remember going up to London with Peggy at the end of the war and standing in the crowds and her looking down at me saying “Isn’t it wonderful Anthony, the war is over”.

At about this time we went to Bournemouth as Gordon was now very ill and in a sanatorium there. To be near him Peggy got a job as a matron in a private school and I became a pupil there. One day Peggy took me by bus to the cliffs overlooking Bournemouth and told me “Daddy has gone to live with Jesus. He has got a special job for Daddy to do because he was a special person.” Vivid now as it was then, I think it was a lovely way to explain my father’s death to me and I didn’t need any more.

Being ill, Gordon had had no chance to establish himself in his profession so there was very little money. Despite being unable to type, Peggy got a job as PA to the manager of Croydon airport which used to be London’s major airport. She then set about writing over a hundred letters to find a Governor who would send me to Christs Hospital, an independent school in West Sussex. She didn’t give up and was eventually successful. In January 1948 at the age of nine I entered the prep school of Christs Hospital. It was and has always been an outstanding school founded by King Edward VI for the sons (and now daughters) of families who are in need. Though wonderful as ‘Housey’ is, it was a pretty daunting place for a nine-year-old, especially one lacking in confidence like me. I can remember the food which was generally revolting and in short supply. We used to buy slices of bread and butter to keep body and soul together. My major pastime was roller-skating which I became quite good at and played many games of roller skate hockey. My time at ‘Housey’ was totally undistinguished. I was neither good at work nor a brilliant frames player and generally felt rather insecure. I played cricket, my best game and rugger for my house but was never good enough for school teams.

Peggy had started a new phase of becoming a sort of universal aunt – going to look after families where the mother had had to go to hospital for some reason. It provided money and gave us a stable base. We moved to Lyme Regis where Peggy became matron at Rhode Hill which was then a girl’s domestic science college and finishing school. We lived in the lodge and it was really like having our own home. I loved it there.

Careers advice was pretty rudimentary in those days. Peggy told me that, concerned at my lack of scholastic ability, she had gone to ask what I was likely to do after school. There was much sucking of teeth and drawing of breath and she was eventually told: “Well I think Anthony should concentrate on just being a nice chap.” At about this time I injured my knee playing rugger and had to have my whole leg in plaster for six months. It didn’t seem to be making progress so Peggy took me to a specialist in Harley Street who also professed to be a faith healer. He took me into a room where we knelt down and said a couple of prayers. All I can say is from that day on I have never felt any pain and I did start playing rugger again. Furthermore, it withstood the rigours of an Infantryman’s life without any problems. Uncanny but true.

Nevertheless, it rather spoiled my plans to be a soldier because all the surgeons told me that my knee would never be strong enough for the army. I got a job with BP but hated it and still hoped to be a soldier. So I reckoned the thing to do was join through National Service where I thought the medical might be less stringent. I didn’t mention the leg and they didn’t find anything wrong. So in August 1958, I went to join Salamanca Platoon at the Regimental Depot of the Devonshire and Dorset Regiment at Topsham Barracks in Exeter.

Basic training was not very remarkable. After ‘Housey’ and the CCF, it was not too difficult at all, but some people had a real problem with it. I was astounded to discover that some twenty-year-olds had never made their own bed or cleaned shoes before. Some could barely read and write. By this time I was too old to go to Sandhurst. I went to Mons Officer Cadet School at Aldershot and received the Queen’s Commission in December 1958. I then embarked on the SS Devonshire at Southampton – a fine old troopship. We had the 9/12th Royal Lancers on board and it was really one long party. We went ashore at Gibraltar and Malta and finally docked at Famagusta at dawn one morning. I commanded 9 Platoon and we patrolled looking for EOKA, a nationalist guerrilla organisation fighting a campaign for the end of British rule in Cyprus, but things were beginning to quieten down and there were no contacts. During this time I had a letter from Peggy who had decided to marry a man named Ted Honore and was going to live in Kenya. I took compassionate leave to help her pack up the house and saw her onto the ship at Tilbury before returning to Cyprus.

We led a very social life, dressed for dinner each evening in the mess, cocktail parties and curry lunches on Sundays and invitations to supper with various married officers. When I was ‘dined in’ to the regiment I had to drink a Regimental cocktail of Advocaat, Crème de Menthe and Cherry Brandy which sat in layers in the glass. After dinner, I had to return to my tent halfway up a mountain in the back of a Landrover and I don’t think I ever felt worse!

On one occasion we had to guard an explosives store at a copper mine at Agasta up in the Troodos. Cooking our tea, one L/Cpl McFie tried to fill the burners with petrol while they were still hot and there was a mighty explosion which sent him flying through the air towards my tent. He was unhurt but the following fire spread rapidly and completely demolished the cookhouse, all our weapons and radios and the ammo. Pretty soon the ammo caught alight and it became like the Fourth of July. My worry was that it might spread to the explosives store which thankfully it didn’t. The next morning, fully six hours after the fire had burnt itself out, the Cyprus Fire Brigade arrived. As the one in charge, I carried the can for the thousands of pounds of British taxpayers’ money that had gone up in smoke. I was lucky to get away with a caution. On another occasion, learning to drive I struggled coordinating hand signal, gear change and steering wheel all at the same time and ploughed straight through a plate glass window into a barbershop. I went back there many years later and the barber shop was still there but had been renamed ‘Reflections of London Salon’.

I then had a spell in Lybia where you could fry eggs on the bonnet of a Landrover. The most memorable event was the earthquake at Barce. A small group of us were the first on the scene to help. We were all in our twenties except for some of my NCOs and we grew up very quickly that night. We all saw things that we hoped never to see again. The locals would call us shouting “bambino, bambino” pointing to a pile of earth. Naturally, we dug furiously and sometimes we did find the bodies of little children but often it was a ruse by the locals to get us to dig up their goods and chattels. By dawn, though, we had collected a large pile of bodies and rescued some injured. The process of clearing up went on for many days. It was an event that made a deep impression on us and I was certainly never to forget that night.

Afterwards, I took some leave to visit my mother and Ted in Kenya. I left my trunk in the care of the night watchman and have never seen it since. Back in the UK, my daughter Karin was born to my first wife Bunty. I had a brief posting to Belfast during the troubles, then on to train recruits in Honiton while Topsham barracks was being rebuilt. There were other postings including Germany and during this period my son Robin was born.

Then it was off to Singapore for three months to learn Malay followed by three months in Hong Kong via Vietnam. Then back to Malaya and jungle warfare training at Khitai Tinnghi just to the north of Johore Bahru. The jungle was wet, hot, noisy and vaguely threatening, I never really felt at home in it. Snakes everywhere and leeches which are revolting. They attach themselves to you as you move through the ‘ulu’ and start off the size of the end of a bootlace but soon become the size of your thumb. I learnt how to survive on what could be found to eat in the jungle and how to recognise what was poisonous. I learnt all about patrolling in the jungle, the rudiments of tracking and how to lay an ambush. We were up against Korp Kommando Operasi – Indonesian Marines and some of their better troops who were tough and well-trained. Patrolling in the jungle was uncomfortable; frequent stops to check for leeches and to check where the hell you were; clinging vines, snakes, creepy crawlies and beautiful huge butterflies. Thigh deep in revolting mangrove swamps then stopping before dark to build a basha for the night – a bed of bracken or groundsheet on sticks covered loosely with another groundsheet. When you returned from ten days of this the smell was unbelievably awful to everyone else. Standing naked in a monsoon to get clean was very simple. The worst thing was being closed in. You never knew what was behind the nearest bush and one operated on a constant state of alert and adrenaline.

At thirty-one I decided to leave the army. It remains the most seminal period of my life. I didn’t achieve anything dramatic but felt I’d done better than most people would have predicted in my school days.

Civilian life began with a job at Unilever in personnel management which was the start of a difficult period. My marriage failed and I worried about the children. Part of my role was to handle industrial relations negotiating with seven different Trade Unions. I quickly realised that almost all problems were not the fault of a bolshy workforce but due to weak and incompetent management. I learned a lot in having to defend my corner against some very tough and powerful people. In some ways, Unilever was like the army – both very large bureaucratic organisations. But the people were not soulmates really. I was part of a small team and missed my “soldiers”. During this time I lived in Sevenoaks and was married to Melita.

This was followed by a stint working for the County of Avon based in Bristol. It was my first experience of politicians and the political process. It is very unsavoury. When politicians use words like trust and loyalty they are not using them in the sense that I know. I learnt soon enough that I couldn’t trust any of them. During this time I remarried again to Carole and my son Robin left home to make his way in Bath while my daughter Karin went to live in Cheltenham and start secretarial college. My job didn’t improve and it was definitely my least enjoyable working experience, my worst ever boss and zero satisfaction. It was also a time of my highest ever salary and the happiest and most fulfilling time in my private life. Well, you can’t have it all – not at once anyway.

The next period of my working life was mostly taken up as a consultant. I had very wide-ranging experience having managed people and events since the age of twenty in a huge variety of organisations and circumstances. I worked for a company and found myself running courses in masses of things – leadership, motivation, team-building, negotiation, presentation skills, time management, communication and so on. Sadly Carole went back to Canada; so a very sad personal period coinciding with a rather fun, satisfying job.

A job I really enjoyed never coincided with a happy personal life and vice versa. How odd.

In time I set up as an independent consultant. I loved this work with clients as diverse as Westlands and a small Nursing Home in Seaton. I worked for pretty well every size and type of company in between.

I am aware that I probably view my soldiering days bathed in a rosy glow. Of course, it wasn’t all good. But I would say that the general standard of performance was much higher than I found in Civvy Street. Of course, there were lazy and incompetent people in the army, but they were quickly identified and they sure as hell were not promoted.

My private life was often difficult. I had only had two role models – one was Peggy’s descriptions of life with Gordon, which as far as I know was one of those marriages made in heaven. I never saw adults disagreeing with each other in a serious way and for some time didn’t understand that good relationships don’t just happen. I rather thought that you fell in love and everything was alright after that and you lived happily ever after. That was a hopeless preparation for life and looking back I am horrified at my naiveté and lack of understanding. Considering the difficulties they had to contend with I am lucky to have such normal and wonderful children. I love them both very much and now my grandchildren too.

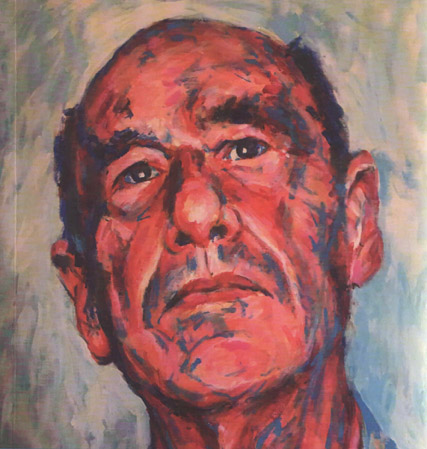

Occupying my time has never been difficult and I am seldom bored. My great joy is painting which I have treated like work in the sense of taking every opportunity to learn and put in the hours of work. I took part in Dorset Art Weeks in 2006 and was staggered to find that 418 people traipsed through my garage to my studio. I like nothing better than to use my painting to make money for the Army Benevolent Fund and the Not Forgotten Association.

I have been extraordinarily lucky to have a wonderfully loving and supportive mother who was a rock for two more generations and loved being both a grandmother and great grandmother. I have also had a wonderful network of supportive friends including my most recent drinking buddies from The Tiger in Bridport who joined me on memorable cruises on the Thomson Celebration and the Norwegian Epic.

Well, it is 2020 now and in December I shall be 82, which is a startling thought. I have lost too much weight – now only 6 1/2 stone. This is rather frightening but my GP is helping me to put some weight on. In any event, I won’t give up and intend to go on living my life to the full. I will not give up without a fight. I continue to love and enjoy my family and friends and know how lucky I am. I will continue to perform random acts of kindness and try to make my little bit of the world a better place.’

Anthony Hurst

Down the Track

West Bay Discovery’s new exhibition ‘Down The Track’ features the story of the railway line that ran from Bridport to West Bay. This year marks the 90th Anniversary of the closure of the passenger service that ran for 46 years. The freight service continued to 1965 when the lines were finally taken up.

There are still reminders of the railway line in West Bay. The station building, despite years of neglect and many other uses is restored, and along with the accompanying train carriage is now the popular Station Kitchen restaurant. The route of part of the railway line is now an attractive cycle track and footpath to Bridport.

The Victorian era was a period of development and there was a great enthusiasm for building railways. There were many options for connecting Bridport to the railway line but when none materialised a group of Bridport Businessmen set up the Bridport Rail Company and the first train ran down the line from Maiden Newton in 1857.

Plans for the West Bay Extension

It wasn’t long before local businessmen saw benefits in extending the line from Bridport to West Bay, then known as Bridport Harbour. A railway offered the prospect of transporting goods, such as sand and gravel quickly and would also support their plans to redevelop the harbour as a seaside resort

So on the 21st July 1879 the Bridport Railway Act enabled the Bridport Railway Company to construct a two-mile extension from Bridport to Bridport Harbour and work started in February 1883. The decision was taken that the station should be named West Bay – a name thought to be more attractive to visitors. At the same time plans were made for the erection of an esplanade and sea wall on the west side of the harbour along with modern residences. This scheme started with the building of Pier Terrace.

The West Bay railway station itself was an unusual design with passengers only being able to access the building from the platform side. The letters BR on the building denote Bridport Railways. The canopy originally stretched over the whole width of the platform (there is currently a model of the station on display at West Bay Discovery Centre).

Work on the line suffered delays, including a navvy’s strike over wages, which were around 2s 6d a day, and a flood. However, following an inspection the line was finally judged to be of “suitable construction and stability” and opening was planned for Monday 31st March 1884.

Opening Day

Opening day saw a carnival atmosphere in Bridport, a great number of passengers travelled down on the first train to West Bay at 7.32am. Overall, 5,100 first day tickets were issued, including 1,100 very excitable Sunday school children who were each given a bun and an orange. The children were however bitterly disappointed that due to the wet weather they were not allowed out of the train, which promptly returned to Bridport. There was grand public luncheon and later a band entertained the people in a field near the station. Obstacle races, bucket-of-water races and climbing the greasy pole were well contested and confectionery vendors set up nearby. Ships in the harbour were bedecked with flags and evening bonfires were lit on the cliffs. With a final cost of £23,000, the West Bay line was up and running.

The passenger service operated with five trains down to West Bay and back each day. Reports suggest that passenger numbers did not meet up to expectations. In 1916 with many staff enlisted in the Great War, the line temporarily closed to passengers. The freight business was still very busy with millions of hemp lanyards produced in Bridport being used by the services along with hay nets for Army horses, ropes and camouflage nets and twine.

The decline of the branch line

In 1919 the line reopened but now it faced serious competition from the new motor buses that were able to run between Bridport and West Bay without having to start or finish at a station.

In the years that followed it also became clear that West Bay would not become a tourist resort to rival the likes of Bournemouth and Weymouth. All there was to show for the previous grandiose plans was the building of a few houses and other buildings to service the holiday trade.

Despite assurances to the contrary, on Monday 22nd September 1930 the passenger train service between Bridport and West Bay was quietly withdrawn. The freight service continued, the Second World War bringing extra business. Shingle was taken from the beach at West Bay for use in airfield construction and train loads of nets were dispatched to the military.

Eventually only one train a week ran, and the West Bay line was finally closed to freight traffic on 3rd December 1962 and in 1965 the rails were finally removed.

The West Bay Discovery Centre’s exhibition highlights stories of the Bridport to West Bay line and those who worked on it. Railway historian Professor Colin Divall has acted as the Centre’s advisor on the exhibition along with Gerry Beale author of The Bridport Branch who has loaned some amazing photos and other material. Brian Jackson, joint author of another book on the Bridport branch has also supported us. The Bridport Museum have kindly loaned artefacts for the exhibition. Wild and Homeless Books in Bridport can supply copies of The Bridport Branch along with a wide selection of other railway books.

A Letter From France

I’m writing this from the Occitanie region of south-west France. I came over with my husband on a Brittany Ferries sailing the day after travelling restrictions were lifted on 4 July.

This was also the day the pubs were allowed to re-open. That night we stayed at an Airbnb in Portsmouth, ready for an early morning sailing the next day.

As we walked our dogs into the city, looking for a fish and chip shop we’d been told was nearby, we could see the bright lights of bars and takeaways. We heard the whoops and hollers of young people out and about, having fun. It was like A-level results day in Bridport, with groups of eighteen to twenty-somethings, enjoying new-found and longed-for freedom.

There were security guards, some of them wearing masks, on the door of every bar, letting people in only when the same number of customers were leaving. Socially-distanced drinkers sat around tables, grinning as if they’d been awarded Olympic medals.

Out on the balmy street, the mood was euphoric. No-one was wearing a mask. The next morning at the ferry terminal, everyone was wearing masks. Crossings to Caen were allowed only if you had a cabin. The dogs and the cat had to stay in the car. Passengers were instructed to stay in their cabins unless going to the cafeteria for time-slotted lunches. Social distancing was insisted upon, as was the wearing of masks in public places.

Down through France, customers were not allowed inside service stations unless they were wearing masks.

After a long journey in which we ran out petrol and the cat escaped (thankfully returning half an hour later), we finally reached our destination, a small village in the south-west of France.

We didn’t have to quarantine but decided, out of respect for our neighbours and to be on the safe side, to keep a low profile for two weeks. We knew how we’d feel if the shoe were on the other foot and how angry we were when some second homeowners broke lockdown restrictions by spending Easter in our west Dorset village, while responsible visitors stayed away.

Other than dog walking in the early mornings and a bit of shopping at the supermarket, we have very much kept ourselves to ourselves. At E Leclerc, we donned our masks and took a sanitised trolley into the supermarket, using hand wash along the way. Not everyone in the store was masked—it’s about fifty per cent—but social distancing is the norm.

France, one of Europe’s hardest-hit countries, has recorded more than 200,000 infections and over 30,000 deaths since the start of the pandemic. The statistics did not stop politicians greeting each other with the customary kisses on the cheek. When a picture showing this was published, the public was furious.

‘You do wonder what’s the point if they can’t set a good example themselves,’ a neighbour said to us over the garden wall.

As I write, the lockdown has been almost entirely lifted. But, like everywhere else, the virus is still here. There are a rising number of cases in the north-west and in eastern regions, particularly in the northwestern department of Mayenne, which has now prompted stricter rules on mask-wearing across France.

As from Monday 20 July, face masks became compulsory here in all enclosed public spaces, including shops where previously owners were able to decide themselves whether customers should wear coverings or not. Anyone caught without a mask faces a fine of €135.

Currently, people can travel freely all over France but are urged to think about whether the trip is necessary. The roads are quiet in France at the best of times but now they are even quieter. Masks must be worn at all times on public transport.

Kindergartens, primary schools and secondary schools are open and attendance is mandatory. High schools and universities have put distance learning in place.

People are being told to protect themselves by washing their hands very often; using single-use tissues and them throwing them away; coughing or sneezing into arms or tissues; not shaking hands or greeting people with kisses on the cheek; keeping more than a metre away from others or to wear a mask if social distancing can’t be respected.

Overall the outbreak is broadly under control across France. But a number of public health officials have warned of a potential second wave, and the government has begun stockpiling hundreds of millions of masks.

In the popular town of St Antonin-Noble-Val, which nestles on the bank of the River Aveyron, the popular Sunday markets have been incredibly busy, although the wearing of masks is obligatory. But, sitting, in the shade having a lunchtime beer, you could be forgiven for thinking things were almost back to normal.

It’s fete season here in France, heralded by Bastille Day on 14 July, which would normally see hundreds and thousands gather for fireworks displays across the land to commemorate the start of the French Revolution in 1789. But this year, things were strangely muted. Large gatherings are frowned upon, although the traditional gourmet market in our village still went ahead on 21 July.

Folk usually sit on long tables to eat their food bought from the various stalls on the perimeter and chat with friends to the sound of a woman singing traditional French songs accompanied by a barrel organ.

This year, the tables were set up separately, to comply with social distancing rules. There were fewer people than usual but it still felt very busy, largely in part because it was one of the only ones for miles around not to have been cancelled.

French borders with other EU member states have been open since 15 June. Our plan is to head for Italy and Greece in September by car, but who knows what tomorrow brings?

Driky van Hensbergen

‘Moving back to Dorset, my childhood home, after a busy life in Bristol until very recently, it seems like life has come full circle. I was actually born in East Sussex in 1988, but in the mid 80s my parents had moved to central Spain, to a house in beautifully wild country near Segovia. My Dad’s a writer and art historian, and he wanted to write a book about Spanish food, so although I was born in England, from the age of about three months I lived in Spain. When I was four we came back, and lived at Burcombe Farm, North Poorton. In the contrasting scenery of the mountains of Spain, and a remote valley in West Dorset, I began to become immersed in the natural world at a very young age. I was encouraged in that direction by my Mum, and my friend Harry and I would explore the countryside freely as 4 year-olds. Spain of course is completely different; dry, hot in summer, and there are vultures, wild boar, and wolves in the area. And here there’s the sea, where I love to swim, so I’m lucky to have a sense of place in both Spain and England, as my family still have the house in Spain where we spend summers; this year is the first time we won’t be going. When I was seven we moved into Bridport, to Victoria Grove, which is where we stayed until I left home.

Both my grandfathers were scientists. One was a soil scientist, working all around the world, including the Bolivian jungle at the time the army were looking for Che Guevara. His group was once arrested because one of them had a beard and looked revolutionary. He was definitely an inspiration to me, so my interest in science does seem to have jumped a generation as the rest of my family are artistic. I have an uncle who’s a zoologist, and my youthful enthusiasm for animals led me to decide that was what I wanted to be, without knowing what becoming one entailed. I took science subjects at school, but didn’t get great A level results because I wasn’t always very focussed on work. I decided I wasn’t quite ready for university, and took a year out to go travelling with friends, spending five months volunteering in Chile, first on a sustainable forestry project, then another project monitoring puma populations, working with an ecologist tracking pumas on horseback, my first real experience of nature conservation in action. There I met David Macdonald, the founding director of Oxford University’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, a globally respected leader in the field of conservation. We’ve stayed in touch over the years, and 10 years on, he’s now the chair of the charity I run. We also visited the Amazon rainforest, then went to New Zealand, worked on a sheep station, an avocado farm, and then hopped our way back to the UK. It was a formative year for me, I’m sure I did a lot of growing up.

I then spent three very happy years studying Zoology at Bristol University. I love Bristol as a city, and I’m really glad I went there instead of London. I found a love of learning through that course, and got a good degree. Moving back to Bridport I spent a year helping a friend, Nick Hill, with local conservation work for the Dorset Wildlife Trust, all good hands-on experience, helping me find my way to whatever came next. That was when I decided to do a Masters in Biodiversity, Conservation, and Management, at Oxford, which took a year. I learned a huge amount that year, particularly from the cohort of other people on the course, who were from all over the world, and started getting interested in environmental policy, corporate sustainability and business practices which were driving environmental issues. After the Masters course I got a job as sustainability advisor for the UK Timber Trade Federation.

My next job was for WWF, a massive global organisation, as Forest Policy Manager in their UK office. Our job was to try and influence the government and the EU to tighten loopholes in legislation around the importation of illegal and unsustainable timber. It was good experience of the intricacies and complexities of working with governments, and I travelled regularly to Brussels, Paris, and to Cambodia where I met all my counterparts from around the world. It was mid-austerity, around 2013, when the government was cutting a lot of funding to Defra who were heavily involved in this work, so at times it was quite dispiriting.

Two things happened while I was at WWF, which were connected. One was that I came back to Bridport to give a talk to students at Colfox school; the other was that I realised I wanted to work much more closely with people and issues at the grassroots. I had had enough of meeting with government minsters and civil servants and producing policy papers that were thrown out into the ether with a hope something good would happen in five years’ time. I wanted to feel the effects of my work first hand. So that was when I decided to set up the charity, Action for Conservation. I had realised that none of the big conservation NGOs were targeting their campaign at teenagers; a lot of work was aimed at young children, then for whatever reason nothing after the age of 12, in the expectation that they would somehow maintain interest through their teenage years, and environmentalists would pop out the other end. I felt that these were the very years when they could connect with nature and be empowered to take action to protect it, on a scale that was meaningful to them. So, at the talk at Colfox I was quite nervous and unsure whether the students would engage with the issues I planned to talk about. But what I found was interest, inspiration and loads of energy right through the room. I came away thinking that if we can only mobilise all these young people, that will be an amazing thing and we stand a chance in turning the situation around.

Twenty to thirty years ago people were more connected to the natural world around them, but in many ways unaware of the global changes already taking place. Now, largely through the internet, people are hyper-aware of issues like climate change and species extinction, but often can’t name the species that live in their street or the fields nearby. So, there’s a disconnect between the environmental improvements that can be made close to home, and the cumulative impact this can have in tackling the bigger issues. Working with some of the people I’d met on the Masters course, and building a network of volunteers, we began the work of the charity by going in to more schools to give talks, and that laid the foundations for what we do now. It is a challenge to keep a young person’s interest in environmentalism as they get older and other responsibilities occupy their thoughts and lives. But our mantra has always been to try and sow the seeds for the next generation of green builders, business people, politicians, and engineers. In other words, anyone can be an environmentalist. Alongside that we need to be a much, much more diverse and inclusive movement and this means creating opportunities for young people who don’t encounter these issues and making the sector more relevant to them and their lives.

In 2016 I left WWF to run the charity full time. It was also the year my wife Sophie and I got married—and moved house. We had appointed trustees, including the writer, Robert Macfarlane. I had asked him for donations of his books as prizes for our crowdfunding campaign when we founded, and made a point of going to collect them in person, so I was able to really pester him about becoming a trustee. He has been a real friend and source of support, as have all our wonderful trustees, and works very hard for us despite being a very busy person.

We are now a national charity with three offices across the country, Bristol, Manchester and London, with a team of paid staff and a large network of over 100 volunteers delivering our programmes. We offer workshops at schools to support students in taking action for nature, and organise residential camps taking young people of different ages into National Parks and giving them a fully immersive and transformative experience. To maintain the inspiration a young person may have experienced on a camp when they get home, often back in the city, we mentor all camp attendees for a further year, helping to drive a youth movement for nature. Our latest ventures include an online programme for young people stuck at home during lockdown, and the Penpont Project, the world’s first, world’s largest, youth-led nature restoration project in the Brecon Beacons, a collaboration between 20 of our young ambassadors and the landowner and tenant farmers on a 2000 acre estate.

Recently, I have been finishing a book for young people called How You Can Save the Planet, that will be published by Penguin early next year. In it are step by step guides to taking action wherever you are, and the stories of 13 young people around the world who have, often in quiet and humble ways, done something wonderful for their environment. And Sophie and I had our first child, Ludo, seven months ago, so we’re glad to be in Dorset for the start of his young life. Life after the pandemic will be different for all of us. Let’s hope it can be greener.’

Up Front 8/20

Growing up in a pub, when my father was also the village undertaker, gave me a unique opportunity to listen to people speak when they had let their guard down. As we all know, a couple of drinks or an emotional experience can often make people more relaxed about speaking their mind. Most of us have an in-built tendency to be slightly careful about how much we give away about our deepest thoughts, and although some cultures and societies are more open, in this country there is a tendency to hold back. However, after a few drinks in the pub, and also, oddly, after a funeral, those directly affected tend to be a bit more open. So in my youth, I had many occasions where people confided in me or happily passed on stories they might not otherwise have disclosed. I don’t fully know why. It’s easy to understand the alcohol effect but why we let our guard down at highly emotional moments or times of crisis is hard to fathom. I’m told it’s caused by a chemical reaction in the brain—which doesn’t really explain much if you’re not a scientist. I remember once in the late 70s getting beaten up after a concert for wearing a Rock against Racism T-shirt. The kicking didn’t bother me much—thanks to a couple of fellow concert-goers I escaped the worst of it—but the embarrassment of how I blathered away to a friendly policeman afterwards has never left me. I think I may have bored the poor man near to death with a breathlessly extended life story, which I liberally laced with pop psychology and an abundance of intense youthful philosophy. In that case, my outburst was explained as adrenaline rather than alcohol, but I still cringe when I think of it. The coronavirus pandemic seems to have had a similar effect. This same honesty and need to open up about the state of the world we live in appears to have affected many people. Families with long-held conflicts—often based on nothing more than misunderstanding and jealousy—have found themselves talking to each other in a way that they never could have before. The same goes for friendships. Long-held grievances, again based on not much, have often been forgiven. And many friendships have been rekindled across the globe. One of my daughters explained that it is because of the collective experience—as we’re all going through it, we are all likely to be more open. It’s surely something to be encouraged. It would be nice to add politics to this list of outpourings of honesty but we seem to have run out of space…

Help at Hand July 20

Steps2Wellbeing (S2W) is a psychological therapies service designed to help people in our community suffering mental or emotional distress. We offer therapies to people who are finding that distress is stopping them living the life they’d like to. We treat conditions like anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (not complex PTSD), low mood and stress.

We have an employment advisory team who offer support for poor mental health affecting work.

Many people come to us for many reasons. Take Liz, finding it difficult having her partner and the kids at home during lockdown because this is when she would compulsively clean the place because of unhelpful and horrifying thoughts that something bad will happen to them if she doesn’t. Add to this that money is tight and her husband may lose his job having been furloughed.

Cecil, who has lost his wife and misses her dreadfully. His family live abroad. He is struggling to manage normal day to day activities because of breathlessness, caused by a long term heart condition and back pain from old rugby injuries. He can’t find the energy or any good reason as to why to bother.

S2W assess and work out with you what sort of therapy will best help. Clinicians are trained and supervised, offering treatments including therapeutic and psycho educational courses, counselling, cognitive behavioural-based therapies, mindfulness programmes, EMDR (a treatment in this service for single incident traumas). Treatment lasts for an average of 10 sessions and many are offered as courses. These are proving to be extremely useful because everyone present, whether therapist or participant, has something to offer and we realise we are not alone.

Being a short term treatment service S2W is not suitable for everyone but we are able to refer to sister NHS teams or advise about other ways to find treatment.

As we are part of the NHS, we are free.

At the moment most work is by phone or digital delivery maintaining safety in these strange times.

At times of severe distress we recommend you see your GP, use 111, Samaritans 116123 or jo@samaritans.org, SHOUT text service 85258 or crisis support 0300 123 5440 for high-risk situations especially those people with strong suicidal thinking.

(All names changed and cases created from similar symptoms but are not real people.)

The Lit Fix July 20

In a new book column, the Marshwood Vale-based author, Sophy Roberts, gives us her slim pickings for July.

I picked up a new reading habit during lockdown. Profoundly distracted, I was unable to click away from the ‘always on’ news cycle. I couldn’t seem to finish anything I started. Discipline, I thought; I would use the opportunity to fill some of those glaring holes in my literary knowledge. I’d take on something big and significant to pull me out of the here and now. Clarissa by Samuel Richardson. Or Moby Dick, suggested an American friend shocked I should have reached my late 40s without having read a word of Melville. Wanting adventure (and some Napoleonic grandeur), I settled upon The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexander Dumas. But when his 1844 epic arrived in the mail, my heart sank at the size of it. It wasn’t the proverbial brick of a book, but a breeze block. I flipped to the last line, on page 1243.

“‘My dearest,’ said Valentine, ‘has the count not just told us that all human wisdom are contained in these two words — “wait” and “hope”?’

Not b**dy likely, I thought. I can’t wait. I have low hope right now. So I put Dumas to one side in favour of a quicker fix. I would stick to books no thicker than a mobile phone. Novellas, short stories, essays. Each one would allow me to escape for an hour or two each day—something I could start and finish in the bath, or before I fell asleep at night—giving me a daily sense of achievement (and much-needed escape) in these otherwise bewildering times. Here’s my shortlist of three.

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd

Robert Macfarlane describes this between-the-wars ode to Scotland’s Cairngorm Mountains as a “slender masterpiece”. What’s remarkable is that it sat in Shepherd’s drawer unpublished for 40 years. I love its poetic economy, the ways Shepherd weaves deep story out of a landscape so familiar to her, and her admission that in spite of a lifetime of walking the Cairngorms’ hummocked snows and gaunt corries, it’s still so rich with discovery. “Knowing another is endless,” she writes: “The thing to be known grows with the knowing.” Above all, I like this book because it reminds me that sometimes what lies right under our feet is all we need to have for an adventure worth telling.

Turbulence by David Szalay

This is a piece of genius from a master of the novella form. He steps inside the skin of twelve passengers on the move around the globe, flying “ahead of the night” over the Atlantic, and elsewhere, to India, Dakar and beyond. With each journey, we meet a secondary character who shifts into the leading role in the next instalment. It’s a clever structure which allows the parts to hang together as Szalay delves into bigger issues, from the loss of a child, to dementia. A book rich in empathy, it has a kind of tragic undercurrent to it as he explores the inner, lonely life of ‘passengers’ on the Wheel of Fate. “It was hard to understand quite what an insignificant speck this aeroplane was, in terms of the size of the ocean it was flying over, in terms of quantity of emptiness which surrounded it on all sides.”

Journeys by Stefan Zweig

Perpetually curious, the Austrian author Stefan Zweig found it hard to be in any one place for too long. Writing between the wars—a period of rising nationalism and economic depression—he also realised that the freedom to travel might not last forever. “Is it the premonition that a time is approaching when countries will erect barriers between them, so you yearn to breathe quickly, while you still can, a little of the world’s air?” he wrote in 1935. This collection of anecdotes about his European escapades is a call for purpose. “Travel must be an extravagance, a sacrifice to the rules of chance, from daily life to the extraordinary, it must represent the most intimate and original form of our taste. That’s why we must defend it against this new fashion for the bureaucratic, automated, displacement en masse, the industry of travel.” Post Covid, I suspect package holidays will never be the same again. Post Zweig, I will certainly treasure serendipity like never before.

Buy any of the books above at Archway Bookshop in Axminster in July and receive a 10% discount when you mention Marshwood Vale Magazine. archwaybookshop.co.uk.

Rural Voices

Through ‘The Inclusion Agency’, writer Louisa Adjoa Parker has been trying to increase understanding between different ethnic groups and seeking out their experiences in the West Country.

Earlier this year The Inclusion Agency (TIA) launched a project which aimed to gather stories from Black, Asian, mixed and other ‘non-white’ people from the south west and other rural areas. The aim of the project was to give a voice to people living in rural areas who are often discriminated against, and to increase understanding between different ethnic groups. The project was funded by Arts Council England and the Literature Works Annual Fund.

TIA have been working to adapt the project in light of the COVID-19 outbreak, and now will deliver the work online—by gathering stories remotely, running online writing workshops, holding online ‘sharing’ sessions for participants to chat with each other, and creating a fictional audio piece, inspired by stories from West Dorset. The project aims to celebrate storytelling, diversity, resilience and legacy. TIA now hopes it will offer some support to BAME people in isolation.

TIA was founded by writer and consultant Louisa Adjoa Parker, and Louise Boston-Mammah, who also works for Development Education in Dorset (DEED). The pair have worked together on many Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) heritage projects over the years, and through TIA they hope to deliver further diverse arts and heritage projects in the region, as well as supporting organisations to become more inclusive.

Where are you really from? is a pilot project that builds on research Louisa carried out in 2018-2019 during her South West Creative Technology Network fellowship. She produced a blog and podcast which showcased her findings.

Louisa says, ‘When the coronavirus pandemic caused the UK to go into lockdown, I felt as though issues such as inequality and racism didn’t seem to matter so much when people were dying in large numbers. However, it has emerged that the virus has impacted disproportionately on those from BAME backgrounds. Although there’s been a strong sense of our country pulling together, racism and inequality sadly haven’t gone away.’

The new project will gather stories of black and brown rural life and share them widely, adding in literary elements including poetry and fictional audio. The project is supported by partner, Little Toller Books, a Dorset-based publisher of books about nature and rural life.

Other artists who will be working on the project are audio technicians and sound engineers Gary Pickard, Matthew Walker, Femi Oriogun-Williams, and poet Saili Katebe.

TIA are keen to hear from people with African, Asian, mixed, and other ‘non-white’ heritage from any rural part of the UK. They are especially keen to hear from people in the West Dorset area over the next few weeks.

Check out the project films: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC_AmIr28X-I3FBV_rxeJzHQ?view_as=subscriber

For further information about the project, and to find out ways you can get involved, get in touch via the website www.whereareyoureallyfrom.co.uk or email Louisa from TIA: louisaparker3@hotmail.com