‘I have loved Dorset from the first moment that I arrived. I was 25 and had never been abroad before. Each new sight and sound was a puzzle, nothing worked like I thought it would from the public telephones which just seemed to eat coins, to the place names like Scratchy Bottom and Dancing Ledge.

So how did a girl from Pittsburgh end up in lovely Dorset and on the cover of this quintessentially English magazine? I often wonder that myself.

I’m from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, an industrial town that centres around three rivers. It’s a typical American city with universities, shopping malls and parks. As a child I remember the smoke stacks billowing smoke from steel mills (but I must say that Pittsburgh has cleaned itself up and it’s now considered one of “the most liveable cities in America”).

My father was a successful business man and my mother was a university professor. How do you follow that? My answer is that you don’t, you chart your own course. I realize now that one of my reasons for moving abroad was to be my own person, create my own world and make my own choices. I suppose the irony is that my parent’s values and support was crucial to my independence but my father gave wisdom without expectation or control; what a totally wonderful gift that was.

I initially came to England for a work placement as part of my Master’s degree. At the time, I was living in Washington DC, a big and fast city that was boiling hot in the summers with a transient population that revolved around the political election cycles. I felt a bit unsettled there and was looking for “my” thing so when I was told by my university to get a placement I decided to venture abroad.

When I arrived I was met by Ian, my host employer who I’d been writing to in order to organise a placement. Ian wanted to introduce me to Dorset and our first stop was Corfe Castle. It’s hard to describe the feeling when an American drives around those winding roads to arrive at this idyllic square which looks like something out of a Disney movie set but is in fact a genuine historic setting. How did they make it so beautiful? That was my first impression of Dorset—authentic, genuine and real. So many things here immediately suited and intrigued me. I liked the natural beauty of the coast and the formality of the people, with their quirky dry wit, loyalty and perfectly timed tea breaks.

My placement was for the NHS in health promotion, and after a year of learning and adapting I knew that this was the place for me so before I finished my student internship, I applied for a job in Dorchester at the health promotion unit. It was a new position based on a government report in the 1980s concluding that preventive strategies were an effective way to decrease mortality and morbidity. Health promotion became a new discipline and my experience and degree gave me the grounding I needed to start this position.

I was offered the job based on an assumption that it would be fairly straight forward to sort out the work permit, but it wasn’t. None of us knew that I needed the approval from the Home Office and so after 3 failed attempts, I went back to the States, defeated. I will never forget the letter that I received when I got home. It said “Perseverance has won the day, we have a permit, when can you start”? I was totally overjoyed and a year after getting the offer, I returned to the UK.

Based in GP surgeries, I worked with nurses to devise and implement health screening sessions. The idea was that through this method, we could connect with patients and offer them new types of strategies to improve their own health and wellbeing. The procedures helped patients make lasting changes to their lifestyle. After feedback from the four surgeries who agreed to trial the project, I was able to offer the programme to all of the GP surgeries in Dorset. I learned about the immense impact that small changes can make on people’s lives.

As a newcomer, I have to say that it seemed incredible to me that the doctors I worked with in Cerne Abbas, who were part of the pilot group, knew so much about their patients’ lives and were happy to make house calls with good cheer and medicines they carried in a bucket. Also, the fact that medical care was free seemed amazing to me and still is. All these years later, access to health care is still such a problematic issue in the States.

A few years later, after I left the health service, I chaired the Kube Gallery at the Bournemouth and Poole College, a glass cube building designed by the renowned architect Richard Horden. We believed there was a huge benefit to the college and the community in opening the same extraordinary gallery space for all to use and enjoy. This “big small building” as it was referred to, hosted classes as well as local, national and international art exhibitions for students and residents in the heart of Poole.

After my divorce, I walked in stages, on my own, from Poole to Padstow, over 400 miles! For me walking on this glorious coast is the most healing and soul-quenching activity there is.

Later on, after raising three wonderful English children, we started the Fine Family Foundation, a charitable trust that creates and supports local projects. The Foundation ethos is based on the lessons that I learned in the health service, that small useful things impact people’s lives and often have a ripple effect on others.

The Foundation provided an entry to work with so many organizations, as well as a platform to use my passion and work with others to add to the quality of people’s lives and help create beautiful things in Dorset.

My first venture was working with the Dorset Wildlife Trust on a new visitors center at Kimmeridge and since then I have relished the pure joy of our beautiful Jurassic coast. I have been down many lanes to get to sites that I never knew existed and worked with people who live and breathe their subject.

In 2012 I had the privilege of receiving an Honourary Doctorate from Bournemouth University for my contribution to the area. I’m inspired by nature and listening to people’s stories so I often seek out projects that help people through the healing power of nature. This can be by stirring up interest, creating something new or planting an idea in the right pot. Two current projects are the new visitors centre on Brownsea Island, a magnificent building based on a treehouse design, and a number of beautiful wooden benches designed by Alice Bogg at Durlston Country Park, which blend so well with the surrounding that they look like they grew there.

We have now supported about 10 visitor centers along the coast, including Durlston, Charmouth, Beer and Sidmouth, giving me close up involvement with the coastal community. There is something about it, which inspired Mary Anning and thousands of others to understand our miniscule and important place in history. Other projects that I’m proud to be involved with are the commissioning of public sculptures at the universities. Another is helping to create an innovate window in the form of a live camera of local nature reserves in the isolation rooms at Dorchester Hospital—we spent hours trying to decide what to do if the camera picked up something embarrassing, but luckily that hasn’t happened! We also brought the inventor of the Gigapan camera to Dorset to train artists and scientists around the county on how to use the camera to tell their story. Recently, we started Park Yoga, a free and inclusive Sunday morning activity, which has grown throughout the country into a fabulous community with so many unexpected benefits for people’s physical and mental wellbeing. In 2022 I have the honour of being nominee High Sheriff of Dorset. Each new project is like a mini adventure which leads to feeling impact, pride, accomplishment, satisfaction, and friendship.

I still can’t believe that I actually live here. Although it may seem accidental, I know it’s not. We are drawn to people and places that suit us. I came to the UK on a whim, looking for my unique path and I feel very fortunate that I have found it here.’

Sibyl King

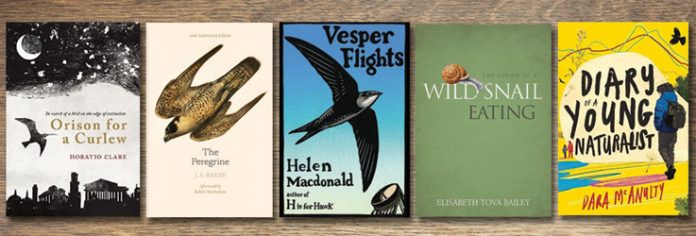

The Lit Fix

Finally, a silver lining to this pandemic to bring in the New Year: a new bookshop has just opened in Beaminster. Little Toller Books, brainchild of the eponymous publisher, is a brilliant new addition to the local literary scene. This month’s slim pickings are some of my favourite pieces of nature writing—something Little Toller has championed in the publishing side of its business—and can all be bought from their new bookshop. I urge you to pay them a visit.

Horatio Clare’s Orison for a Curlew may be prose, but his elegiac lyricism makes the pages of this book read like poetry. Clare traces the migratory passage of the slender-billed curlew across southern Europe and the Balkans, as he searches for this possibly-extinct bird. The narrative is darkened by many of the issues that plague modern conservation efforts—habitat destruction, hunting, pollution—but is lightened by exquisite descriptions of ‘dozy dolomitic scenery in ageing lemon sunlight’, clouds of black storks jumping like ‘an ambush of Hussars’ and philosophic musings from the people he meets.

Peregrine by J.A. Baker is over half a century old but remains as gut-grabbing now as when it was first published. An intense, exultant narrative, it follows Baker’s life-long obsession with peregrine falcons in Essex. His imagery is visceral prose: a dead wood pigeon ‘purple and grey like broccoli’, ‘clear black lunar shadows’ and a darkened ridge with ‘a bloom on it like the dust on the skin of a grape’. No less engaging is the author’s consciousness of his own species. ‘We are the killers. We stink of death’, writes Baker of human impact on the natural world. And yet ‘Nothing is as beautifully, richly red as flowing blood on snow. It is strange that the eye can love what the mind and body hate.’

Helen Macdonald’s hotly-anticipated Vesper Flights is a collection of essays. She takes us from the vanishing countryside to the vespers Macdonald chants as she tries to sleep, with one of the best pieces taking us to the very top of a tower block in New York City. This is an intimate portrayal of loss, personal connection to nature and musing on the destruction of our fellow species. The title—relating to evening devotional prayers ‘the last and the most solemn of the day’—was chosen, MacDonald writes, because it’s ‘the most beautiful phrase, an ever-falling blue’. The tone of the narrative is set…

Elizabeth Tova Bailey’s The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating is a quiet narrative that packs an outsized punch. Suffering from an undisclosed illness, Bailey finds solace in a wild snail, which she keeps in a terrarium by her sickbed. From observations on molluscan anatomy to the snail’s various daily habits, the author falls into the rhythm of its life and movements. The snail helps her find a greater understanding of her own place in the world—with survival sometimes dependent on something as ephemeral as noticing ‘the way the sun passes through the hard seemingly impenetrable glass of a window and warms the blanket.’ A wise, subtle book about living with chronic illness and how appreciation of the smallest details in the natural world can deepen our lives.

Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty was one of 2020’s publishing sensations. The narrative follows a year in 15-year-old McAnulty’s life after his family moved from one region of Northern Ireland to another. Written in diary-form, McNulty explores his connection to wildlife and the way he sees the world; about his dream of ‘enabling our own wildness’ because ‘We need to feel the earth, and hear birdsong. We need to use our senses to be in the world’. McAnulty was diagnosed with autism and Asperger’s as a child; this experience is closely bound with his writing and communion with the natural world.

Impressions of a Landscape

How the Marshwood Vale inspired the work of two great artists.

The hamlet of Hewood sits almost organically in its surrounding landscape, tucked neatly into the folds of the valley. Trees caress its sides, softening the edges of buildings and blurring the boundary between man and nature—a suggestion of the communal respect for this land that has been passed down through generations. The stretching horizon—so often blotted with pearly cloud—frames this scenery in a subdued, delicate light and outlines the undulating profile of distant hills. There is a pastoral timelessness in this place, striking both a sense of calm and flaring imagination; space to think and time to do. It was therefore little wonder that here, buried within these layers of green, two great artists and friends, Lucien Pissarro and Harry Banks, found their source of divine, creative inspiration.

Though he would eventually come to live in this small corner of the world, Pissarro was brought up far from the muddy lanes and thatched villages of west Dorset, instead growing up in a leafy suburb of Paris, the eldest child of the eminent impressionist painter Camille Pissarro (i). Between time spent in and out of his father’s studio, Lucien became familiar with the artistic world through exposure to great talents, such as Claude Monet and Pierre Auguste Renoir—who both frequented the Pissarro family home(ii). It was almost inevitable that Lucien too cultivated a personal penchant for painting, initially developing a style similar to Camille and his contemporaries; employing thin, yet visible brushstrokes to depict the ephemeral beauty of dappled, changing light.

Following several trips to England, and a stint working for an art-publishing firm in Paris, Lucien moved to Chiswick, North London where he worked primarily in book illustration and was a founding member of the influential Camden Town Group of Artists(iii). During his years involved in both the London and Paris art scenes, Pissarro found himself emerged within a milieu of many other avant-garde artists, including Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Signac: who were both busy carving what would later be recognised as the new boundaries of modern, expressionist art. In fact, a rather rough, sketchy portrait drawn by Pissarro in 1887 is thought to be the only depiction of Vincent and his brother Theo—alluding to just how unrivalled Lucien’s access was to other revolutionary creatives of this era(iv). Vincent also showed fondness to Pissarro through his own artwork, tenderly dedicating the painting, ‘Basket of Apples’ (1887) to “à l’ami, Lucien Pissarro(v)”—‘to the friend, Lucien Pissaro’.

However, as someone who loved to paint outdoors, Pissarro grew restless of printing in the city and frequently visited properties in Essex, Sussex, Devon and Dorset to take inspiration from more natural subjects. His passion for rural scenery is apparent in the sheer bulk of his work produced during such stays, which feature bright, airy landscapes and endearing tree-lined lanes—almost symbolically representing his own impulses at the time, drawing him into the thicket of country life. Of all of these places though, it was the enchantments of Dorset’s golden coastline, magical hillforts and steep, wooded valleys which pulled the strongest, and eventually lured Pissarro and his family permanently in 1914(vi).

After renting a crumbling cottage in Fishpond—from where Pissarro painted several wonderful pieces, including ‘The Heather Patch’ and ‘High View, Fishpond’—the family finally settled in a handsome property in the secluded hamlet of Hewood. Hewood is one of those rare places that still today feels relatively untouched by modern times; with the whole hamlet under a group listing, it is a gem seldom known to the rest of the world. At the heart of Hewood is a small green, where you’ll often find cattle and goats grazing, seemingly unaware of the centuries that have passed since the surrounding cluster of cottages was built. Pissarro’s own affection towards the enduring charm of Hewood is translated in the plodding pace of rural life which he exquisitely captured within his work. Though still in their subject, the vibrancy of Pissarro’s oils evoke a heady nostalgia for the bursting hedgerows and fleshy, ripe grass of summer’s warm days. The sheer length of time Pissarro spent in Hewood is too a reflection of his enjoyment there, as he proceeded to paint the local landscape for 30 years, right up until his death in 1944; his daughter, Orovida allegedly rolling him out in his chair across the countryside in the frailty of his last few years.

During his time in Hewood, Pissarro was visited by various friends, including the talented etcher Harry Banks—whom he met during his involvement in London’s printing scene. Banks enjoyed an esteemed career himself, exhibiting at the Royal Academy in Paris and America and also being selected to design the invitation for Edward VII’s lavish coronation dinner in 1902(vii). Like Pissarro, Banks also found himself falling for the local landscape, moving into the neighbouring hamlet of Synderford, saddled on the banks of the bubbling River Synderford. With his exchange of the tidy streets of Chelsea for Dorset’s meandering lanes, the focus of Banks’s work shifted too, as he composed looser, subdued watercolours and atmospheric etchings to depict his new bucolic surroundings. Among its many patchwork hillsides and sunken paths, Banks—like Pissarro—also sought to record those who inhabited this land, setting up his easel in mucky farmyards and crackling wheat fields to observe the slow workings of rural life.

I often find myself wandering along the same lanes, which plunge down into the depths of the Marshwood Vale, thinking of these two artists—and every time I can’t help but feel a tingling creativity inside of me. Though not as artistically blessed, my twitching fingers instead turn to write, in my best efforts to incarnate a similar awe of the unfolding landscape as those two men who curiously trailed these paths before me.

[i] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucien_Pissarro – Wikipedia: ‘Lucien Pissarro’

[ii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucien_Pissarro – Wikipedia: ‘Lucien Pissarro’

[iii] https://www.christies.com/lotfinder/Lot/the-eragny-press-1640158-details.aspx#:~:text=In%201894%20Pissarro%20and%20his,the%20Fishes%20(number%20i) – Christies: The Eragny Press’

[iv] https://www.theartnewspaper.com/blog/vincent-in-conversation-with-theo-identified-as-his-companion-in-ashmolean-drawing – The Art Newspaper: ‘Theo Van Gogh is identified in mystery drawing now on show in London’

[v] https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/lucien-pissarro-r1105344#fn_1_1 –Tate: ‘The Camden Group of Artists in context’

[vi] http://www.thorncombe-village-trust.co.uk/page34.html – Thorncombe Village Trust: Pissarro at Hewood

[vii] http://www.thorncombe-village-trust.co.uk/page68.html – Thorncombe Village Trust: Harry Banks

This Good Earth – and our part in its future

Filmmaker Robert Golden’s latest film, a powerful statement about the planet on which we live, is scheduled for a world premier in Bridport in January. He spoke to Fergus Byrne.

Documentary filmmaker, Robert Golden, had a powerful motivation for making his latest film: ‘They are killing people’ he told me from his home outside Bridport. ‘These people should be arrested and charged with crimes against humanity.’ It is Robert’s strong belief that politicians, indeed governments across the world, are in the pockets of large corporations that are ‘perpetuating market places and ways of doing things that are actually going to kill their grandchildren.’ He goes on to say that these corporations are ‘already causing terrible destruction around the world’ and says ‘there is not much difference between them and the SS of the Second World War.’

These potent and damning beliefs are part of the reason he was compelled to make his latest film, This Good Earth, which is to be premiered in Bridport on 21 January at an event that will be live-streamed around the world from the Bridport Arts Centre. Afterwards there will be a discussion with Robert Golden and several of the interviewees from the film about the necessity and power of storytelling to bring change. Tickets will be available in the beginning of January from the film’s website, https://this-good-earth.com.

A ninety-two-minute documentary, This Good Earth paints a picture of global food markets skewed for profit, with farmers strangled by the greed of businesses whose motivation is naked self-interest. It is the story of a food system that causes environmental destruction, obesity, hunger and increasing levels of food-related diseases. A story of how intensive farming—using agrichemicals designed to create efficiencies and higher profits for large corporations—is damaging resources to a point where some may never recover. The film also highlights the enormous amounts of workers poisoned by pesticides, quoting a figure of 40,000 fatalities; a number that doesn’t attempt to include the huge impact of long-term health issues.

The film came about when Robert had been asked to make an update to a locally-based episode from his Savouring Europe documentaries—a series of beautifully filmed profiles of food production from different countries around the world. However, the idea of making an update changed. ‘It became less and less a celebration of what’s around here, although of course in some senses it is’ he explained ‘and more and more a critical look at what’s going on in our world.’ He found himself drawn back to research he did on a project many years before, then titled Toxic Harvest. It had been shelved due to the 2008 economic crash. But the lessons Robert learned from that, along with his need to tell that story, had never left him. ‘I decided to take all the different elements from soil all the way through hunger and bad diet and disease and show them as a whole picture, and pay attention to the fact that we live in a holistic world. The degradation of soil has a direct link to climate change and people accessing food.’

He learned an enormous amount from the farmers, producers, scientists and professors he had interviewed when researching the project. ‘I began to realise that not only was it a much darker story than even I could think of—and I have a pretty dark view of the world—but that the connections were even more sinister. That’s when I began to understand that I had to make different kinds of linkages. The soil question is directly linked to climate change; the question of landscape is directly linked to the disappearance of species, and the long food chain is definitely linked to peoples’ illnesses.’

He hoped that step by step, the story would be clear. ‘But there was an underlying thing I wanted to do which is basically to say, “look at how extraordinarily beautiful this planet is”. Seduced by the beauty of the earth and its stunning landscape, Robert hopes that people will ask who is really causing destruction and why is this happening. ‘We all know the answers’ he says. ‘I realised that all these professors and the farmers know what the answers are. It’s not a question of a lack of knowledge; it’s a question of something else. And the something else, obviously, is a combination of policymakers, politicians and corporations whose vested interests are not to let anything change. So they mendaciously stand in the way just like the tobacco companies did, knowing full well the consequences of what they are doing, and yet still doing it.’

Although discussed in dozens of books, reports, magazine articles and television documentaries over recent years, each view offers fresh eyes and this is a story that, as Robert points out, needs to be told as often as it takes to stop the destruction of the planet and the poisoning of its people.

Set in and around West Dorset, the film is beautifully shot and simply presented without the use of a narrator. It is told using comments from farmers, producers, scientists and academics whose compelling arguments against the tactics and philosophy of large agrichemical, distribution and sales organisations, makes it clear that this message cannot be ignored.

In the opening scene, a local farmer walks through a freshly ploughed field using his feet to kick through and test the dry soil. The ground he walks on is the starting point of the growing cycle and the source that constantly gives up nutrients for the benefit of whatever is harvested from it. The first segment of This Good Earth makes the point that without constant care and respect, the organic material that creates the nutrients that allow plants to thrive will no longer support our needs. Decades of chemical intervention to try to control nature has made and continues to make it harder and harder for the soil to survive.

In the film, interviews with local farmers are interspersed with testament from scientists and officials such as Tim Lang, Professor of Food Policy at City University London’s Centre for Food Policy; Erik Millstone, Emeritus Professor of Science Policy at the University of Sussex; Jules Pretty, Professor of Environment and Society at the University of Essex and Liz Bowles from the Soil Association. Set against the backdrop of West Dorset small-scale farming, their comments starkly highlight the need to wake up to the damage intensive farming is doing.

Aware of the corporate need to create efficiencies to increase yields and therefore profits, Ellen Simon at Tamarisk Farm points out that, small-scale operations like hers are obviously not the most efficient in terms of output, but they, therefore, do not contribute to global warming in the same way. Relying on local markets, smaller operations, especially organic and those supplying local markets are not so much bound by the rules of forces out of their control.

Philip Colfox from Symondsbury Estate talked about how the lack of contact with the customer left many farmers trapped in a cycle they had no control over; a cycle where an intermediary supplied the raw materials including agrichemicals to help increase yields, and then, through a related intermediary, purchased the harvest. It was a system that tied the farmer to a process which had to be adhered to or they would be quickly dropped as a supplier. ‘He’s stuck in a vice and not able to negotiate his own price’ explained Philip. ‘He’s not able to create his own products to sell to his customers, he’s just growing commodities.’ This made it very difficult for the farmer to do what he could be proud of; ‘to simply create good quality food for the customer. He’s just someone running a sort of factory, almost a captive in the good old-fashioned sense—and he’s sold his soul to the company store.’

Buyers that dictate what is grown have less interest in the long term view that environmentalists or those concerned with health issues share. Profit over a small number of years is their motivation and one that results in land use more likely to destroy nutrients and local ecosystems rather than allowing them to regenerate or thrive.

That loss of nutrition and the residue left by chemical additives also help produce products that lack the same natural health value; products that may indeed feed the many, but with little thought for their long-term health.

Erik Millstone, Emeritus Professor of Science Policy at The University of Sussex points out that ‘after agrochemicals have been sprayed on land and crops, they inevitably contaminate the food that we subsequently eat. And while it’s common for officials and their government advisors to say “Oh the residual levels are safe” I’m not at all convinced. On the contrary, I think there’s quite a lot of evidence that even the pesticide residues in common foods are problematic.’ Professor Millstone wants to see a proper system of testing and assessment that he says ‘ought not to rely just on evidence from chemical companies but also from independent scientists such as academic scientists or people working in public health institutes.’ He says that all evidence gathered should be registered and pooled so that companies can ‘no longer have the option of concealing unfavourable evidence.’

Diet and our over-reliance on mass-produced meat is a problem that has become a much-debated issue. Talking of the overuse of land for animal feed and the lack of concern for biodiversity, Tim Lang, Professor of Food Policy at City University London’s Centre for Food Policy, says ‘the figures don’t add up’. If we only focus on the short-term needs of humans he says: ‘basically the planet stops functioning.’

Jules Pretty, Professor of Environment and Society at The University of Essex points out that we pay four times for the food we eat; first at the till, then for the cost of cleaning up the environment and thirdly in Government subsidies from our taxes. On top of that, he says there’s actually a fourth way that we pay for our food and that is in the result of the choices that we ultimately make about the food that we eat. Those choices are not necessarily free choices; ‘they are constrained by our own resources’ he says, alluding to the food poverty that has seen a huge increase in food banks, ‘or strongly shaped by advertising or other corporate interests to encourage us to eat certain sorts of foods. The result of that is that a large amount of ill health worldwide now is related to the kinds of foods we do eat.’

This Good Earth focuses on three elements; soil, land and food. Within these three broad subjects, the film tackles a myriad of issues that cannot be described in a short article. However, the message is clear and the film asks for our response and action to deal with a system that can easily be interpreted as criminal.

Tim Lang describes a truth that is all too often apparent. He talks of the fantasy world of hour after hour of ‘TV chefs tantalising, and competitions tantalising you with totally unaffordable foods and tastes’ against the reality of very big companies, ‘trying to sell you cheap pap which is tasty, sweet, fatty, lovely instantaneously, but makes you obese and you die early.’ He believes ‘diet is one of, if not the major cause of premature death.’

Patty Rundell from the International Baby Food Action Network cited the addictive nature of sugar: ‘You get hooked on sugar’ she says. ‘It is addictive, all these things are addictive and they know it. And the corporates behind it know exactly what they are doing in the way that they sell it to us.’ She cites how the baby food sector was one of the first to pinpoint something called ‘commerciogenic malnutrition’—a term for something that means you actually cause harm or death by commercial practices.

While many people make the point that social movements are vital to help affect change, it is also clear that the law must play a role in challenging these commercial practises that could be seen as criminal. Human Rights Lawyer, Richard Harvey, makes a point that echoes Robert Golden’s belief that there are criminal activities to be dealt with. ‘Food is big business, very very big business’ Richard says. ‘Just like oil, just like gas, these are substances that really are all about money as far as the big manufacturers are concerned.’ He says that while we know what we should be doing to the land and what we should be eating, ‘the really smart people that run those big businesses’ know that better than anybody, because they’ve been studying their industry and how to manipulate it for years. ‘So when you know that the quality of the food that’s being produced is actually damaging the people that it is destined for, it’s a bit like saying that you are poisoning them. And there are laws against poisoning.’

He says that one can prosecute a CEO or the very highest board members of those companies, but he also knows there are strong forces in play and doesn’t believe the law is the final solution. ‘There are clearly cases where the companies control the courts to the extent that individuals have got very little chance of winning against them’ he says. But he believes we all have a human right to a clean, healthy, safe and nutritious environment, one that is all about human dignity. He asks a hopeful question: ‘isn’t that really what we all want?’

Robert Golden believes that ‘corporations own most of the politicians and the political parties’ and that one way or another, big business is able to put huge pressure on politics. He believes their terror of potential unrest by interfering with existing food systems is part of the reason for political inertia. ‘I think a combination of their terror and their pocketbooks and their paying for elections means they are not servicing us—they are servicing the corporations.’

This Good Earth makes a solid case and although it doesn’t set out to offer all the answers, dissecting the issues is a way of finding a route to a better future. Perhaps there is the chance that a combination of the law, along with social movements for change and individual efforts to live better can alter the future for our grandchildren—but only if everyone cares about their grandchildren.

Stonehenge keeps Growing

I normally write about this topic for the Winter Solstice, but missed it last year. However I can now wish readers a Better and Happy New Year!

Stonehenge is growing mainly in our knowledge, due to modern archaeological methods and increasing aids. But also it is growing in size and information provided on TV, radio and newspapers. As an engineer I am amazed at the way early people managed to move and erect the large stones, without our tractors, cranes and power tools and only stone axes, antler picks and ropes of twisted vegetation. Also their design capability and man-management, not forgetting making contact as far away as Scotland without telephones. So I share some recent information, as follows :

Last June The Guardian newspaper reported that a circle of deep shafts has been discovered near Stonehenge, forming a circle of 1.2 miles (2 km) in diameter. Durrington Walls Henge is precisely at its centre, 1.9 miles north east of Stonehenge. Each shaft is more than 5 metres deep and 10 metres in diameter. Twenty have been found so far at an average of 8.64 metres from Durrington Walls Henge. The circle also encloses Woodhenge and crosses a causewayed enclosure near Larkhill. There may have been over thirty shafts. The shafts have filled in naturally and were earlier dismissed as sink holes or dew ponds.

Professor Vincent Gaffney of Bradford University, who announced the findings, believes they may be greater than 4,500 years old and hence contemporary with Stonehenge and Durrington Walls. The circle appears to have included the Larkhill causewayed enclosure, which is believed to be over 1,500 years older than Durrington Walls. The investigation involved a consortium of Bradford and Birmingham Universities and one in Vienna.

Worked flints and bone fragments have been found in the shafts. Planning the circle must have involved pacing over 800 metres from the henge outwards and so must have involved a counting system or some sort of tally. Professor Gaffney believes it to be an incredible new monument, providing an insight to the past, of an even more complex society than we have imagined.

I have just discovered that I had overlooked a newspaper article by David Keys from 2012, describing Stonehenge as an art gallery. A laser scan of the monument discovered that five of the largest stones have carvings to be viewed from the north east, probably during processions at the solstices. At present these carvings are invisible now to the naked eye, having been chipped very finely. There are 72 carvings, dating from Early Bronze Age, 71 represent axe heads and one a Bronze Age dagger. It is suggested that real axe heads were used as stencils, up to 46 cm long, but larger than any actual implements so far discovered. They are believed to date from 1800 to 1500 BC and face nearby burials of the period, or the centre of the monument. The work was carried out for English Heritage by the Greenhatch Group from Derby and analysed by York Archaeological Trust.

In July English Heritage reported that they now believe they know the origin of the source of the large 20 ton sarsen stones for which Stonehenge is famous. Apparently during repair work in the 1950s a core sample was taken by drilling with diamond tools from one of the large 22ft stones. One workman took part of the core sample home as a memento and subsequently took it when he went to live in the USA. He is now 90 years old and asked his sons to return the sample to English Heritage, where it has been chemically compared with sarsens from Devon to Norfolk. Susan Greaney, one of the English Heritage authors of a recently published paper, believes that its origin is West Woods, near Marlborough in Wiltshire, about 15 miles from Stonehenge. Just the far side of West Woods lies the road from Marlborough to Avebury and adjacent to the road lie many large sarsens, commonly known as “Grey Wethers”, an old name for sheep. I have always considered this to be the source of the Stonehenge and Avebury sarsens, so I was not far out!

Professor Alice Roberts reported in October that excavations at Bulford, 3 miles to the east of Stonehenge by Phil Harding (of Time Team fame) and others had discovered two previously unknown henges, in fact a double henge. An unused stone axe, chalk balls and a decorated pot, perhaps late Neolithic, were found. Forty pits were excavated, containing a number of aurochs bones, several times larger than our domesticated cows and thought to be sufficient for a large feast, possibly for their religion. These people could have witnessed the erection of Stonehenge, 4,500 years ago. Later people left evidence of new skills, first the Beaker people and then metal working. Another excavation, towards Amesbury, at “Vespasians Camp” about one kilometre from Stonehenge showed human evidence from the Mesolithic period, with flint tools. Also animal bones some 8 or 9,000 years old, e.g. a wild boar tusk and aurochs bones. This is 3,000 years before Stonehenge was erected.

So it is gradually appearing that a large area around Stonehenge was in use before and after the erection of the monument. After its erection the use of the wide area seems to be for burial purposes of cremations, as a “hallowed ground”.

Some 14 miles, 30 km from Stonehenge is another henge which has only been fully investigated in the last 10 years. This is at Marden in the Vale of Pewsey, near Devizes in Wiltshire, described as a “Super Henge” on Radio 3 in April by Penny Bickle and Jim Leary. It is the largest known henge in Britain. Traces of a hut with a large central area of chalk/stone and remains of flint knapping and feasting on cattle and pigs were found. Some of the animals came from Scotland, according to strontium analysis, similar to those at Stonehenge and Durrington Walls. Post holes of a trapezoidal building, 20m long by 10m wide with timber walls, possibly Neolithic, maybe 3,800 BC, were found. Flat pieces of chalk engraved with marks were found in the post holes. The building might possibly have been a community hall, perhaps 7,500 years ago. The dwellings of the time would have been very smoky and residents would have ingested carbon.

This September Professor Alice Roberts added more detail about the Marden Henge, which had a bank and ditch about 10 times larger than Stonehenge. A large circle showed traces of houses, inside the henge, one of which had a large fireplace or hearth, possibly for a sauna or “sweat lodge”. Hot stones could have been carried inside and water poured over them. A second large hearth was also found, with no charcoal, but there were traces of a bonfire and a burnt sarsen stone. Near the entrance to the henge in the ditch a Neolithic burial was found of someone of mid teens, with amber beads and beaker remains of 2,000 to 4,000 BC. Later remains in straight lines were also found nearby, possibly Roman.

The Penguin Guide to Prehistoric England says the Marden Henge was oval shaped, of 14 ha, with bank and internal ditch, except on its south and western sides where the River Avon encloses it. Entrances were found on the north and east sides. A mound, the Hatfield Barrow, once stood 6.8m high inside which was excavated in 1807 by William Cunnington, but little was found and soon after it was destroyed. Excavations in 1969 found the northern ditch was over 15m wide, but only 1.8m deep. Grooved ware, antler picks and flint tools were found, with evidence of a timber circle 10.5m in diameter with 3 posts for a possible roof support.

As I write this I hear that a road tunnel will take traffic out of sight of Stonehenge soon. I wonder what may be found during the excavations?

Bridport History Society opens the New Year via Zoom at 1.30 for 2.30 pm on Tuesday 9th January 2021 when Dr Todd Gray will describe “Exeter in the 1700s: the golden years of the cloth industry”. For Zoom details contact Jane Ferentzi-Sheppard on 01308 425170 or email jferentzi@aol.com.

Best wishes for a better and Happier New Year.

Cecil Amor, Hon President of Bridport History Society.

The Drift Road – a lost village workshop

The Dorset Diggers Community Archaeology Group was set up in 2012 to work in the community to facilitate the study of Dorset’s deeper past. That means that we are not just a hobby group, but to actively engage local communities in doing all aspects of research. Our first site was proof that archaeology does not always have to be about looking for aretfacts and structures from thousands of years ago, but also those that lived closer to our own time, now forgotten.

I was sitting in my village cafe in Maiden Newton when a villager came up to me and asked if I would be interested in looking at a structure up on the Drift Road/Old Sydling Lane. We walked there, whereupon I saw what looked like a water trough. From the trough a narrow mound of grass ran toward the hedge lining the lane. From the style of brick I thought that the structure was probably about one hundred years old, but still worth looking at. No one could say why this large structure was sitting in the field, as animals troughs are usually much smaller and connected to a water supply. We were asked to answer this question, so we set about digging.

We found that the mound was made up mostly of brick and tile and would need some serious hitting with mattocks to clear away. After that was cleared we had found a whole building, constructed from chalk and flint with the trough attached to it! The structure was divided into two rooms by another narrow chalk wall. The northern room had a brick wall on top of a flint foundation facing the lane, but this wall would not have been load-bearing and may have supported a timber partition that could have been opened to people using the path. The floor was divided into two parts, one cobbled and the other compacted earth. The cobbled flooring may have been the work area or as a hard standing for horses. The southern room had a compacted dirt floor, with a double door facing east. The finds made it highly probable that this was a small workshop dealing in metalworking relating to the repair of cart wheels and horse equipment.

The bricks were made by Colthurst & Symons & Co in the 1850s, leading brick makers in the Powerstock area. Metal waste comprised of nails, bars, hooks, brackets, door bolts and wheel rims. Two penknives had bone handles, the blades having corroded badly. A bridle bit with a twisted mouth piece was dated to the late 19th century or early 20th by a visiting horse rider who arrived within just a few minutes of the artefact being found! Bridle bits are now made smooth, as this is not so hard on the horse’s mouth.

A Camp Coffee bottle was found in perfect condition, embossed on three sides with “ESS CAMP COFFEE & CHICORY”, “GLASGOW”, “PATERSON”. Camp was founded in 1876, but the same design appears on adverts in the 1940s. A vet’s bottle was found close-by, intact, with a glass stopper. It was embossed “ELLIMAN’S ROYAL EMBROCATION FOR HORSES MANUFACTORY, SLOUGH” and is possibly late Victorian, but this was still being used in the early 1980s. It was for rheumatism, sore throat, sore shoulders and backs, capped hocks and elbows!

A glass stopper had the stamp WRIGHT & CO., based in Staffordshire. Further research was done on this company, the scene of an industrial accident where a glass kiln exploded. One worker was killed by the explosion and two others were killed by being engulfed in molten glass. Once the glass had cooled it was found that only hobnails and belt buckles had survived, so the remains were kept in glass blocks and then the whole buried. It was reported that the owner of the company told the men at the funeral that “they would have to work harder to make up for the loss of three employees”! However, the firm did not last long and went out of business soon after.

Archaeology is about our collective memory, in this case the structure we were excavating had been quickly forgotten, a structure that told a story of a local business much needed up to the time of the internal combustion engine took over the work of horses in the 20th century. Even though it was only a century since demolition it had been lost to us and the only way to recover that memory was to undertake an archaeological investigation. It can now be seen by a new generation.

Working for a Better Future

Back in November, Margery Hookings invited community leaders in towns in and around the Marshwood Vale to tell readers about their hopes and plans for 2021. After a year dominated by coronavirus, all of us are looking forward to a brighter future when we can look back on the pandemic with relief that it has passed. Not all towns responded but here are some of the comments we received. Our thanks to the community leaders here for taking the time to share their hopes and plans for the new year.

SIDMOUTH

Ian Barlow, Chair of Sidmouth Town Council

In what has been a challenging year for most, Sidmouth has seen the completion of a number of major projects. Firstly, in collaboration with Visit Devon and our marketing partners, Ignyte Ltd, we have completely updated and improved our town’s tourism website, making it much more user-friendly and giving local businesses more opportunity to promote themselves. This has already seen a huge boost in tourism to the town, which we hope will continue into 2021. A new website focussed on our residents will be following shortly.

A number of projects have also taken place within Sidmouth and the Sid Valley, making the town even more attractive and providing more activities for residents and visitors. This includes the opening of a new skate park and the new Alma Bridge, which allows easier access to the south west coast path. As well as this, Sidmouth has taken ownership of Knowle Parkland, providing even more public open space for residents and visitors to enjoy. The space includes gardens and a new amphitheatre allowing for even more iconic events to take place in Sidmouth. While many of these have been postponed for 2020, annual celebrations, including Sidmouth Folk Festival, have already confirmed dates for 2021, so we can all agree that there is plenty to look forward to.

SEATON

Ken Beer, Mayor and Chairman of Seaton Town Council

Seaton Town Council is looking forward to a busy 2021 working with Seaton’s famous attractions such as Seaton Tramway, the Wetlands and Seaton Jurassic. Seaton will also play host to new events being organised through the Promote Seaton Group—a working party comprising councillors, business owners, community groups, residents and other local stakeholders.

Subject to any restrictions still in place next year, we hope that we will once again welcome established events such as the Grizzly Run, CycleFest, Natural Seaton, Seaton Carnival week, with other new and exciting events in the planning stages. Seaton always welcomes visitors to enjoy our wonderful independent shops and eateries and our spectacular coastline.

We are helping our local businesses improve their premises and encouraging coach operators, by providing better facilities.

The accessible seafront, with its far-reaching views across Lyme Bay, attracts visitors in all weathers and plays host to a variety of activities for all ages, including paddle boarding, sea fishing, swimming or simply enjoying a family picnic on one of the cleanest beaches in the South West.

We look forward to seeing you in 2021.

BRIDPORT

Ian Bark, Mayor of Bridport

The people of Bridport have risen to the challenges by supporting each other in so many different ways. We have come to realise how valuable our local businesses are and how important it is we give them our support. Perhaps the most important hope for 2021 and beyond is reigniting the Green agenda. There is much work to be done and we need to be brave in our actions. Future generations will not forgive us if we fail to act now.

Dave Rickard, Leader of Bridport Town CounciI

The town council will need to maintain its involvement in the pandemic’s consequences but we also want to press on with some of our key strategic aims, such as responding to the climate emergency, developing plans for the town centre and building on our Rights Respecting work.

I would also like to see our reputation as ‘Dorset’s Eventful Town’ restored to the full—and, if possible, extended. Arts and cultural events can help our local economy to recover from the ravages of Covid19.

It won’t be an easy year and we need to plan our financial recovery alongside delivering our plans. As the leader of a ‘can do’ council in the ‘can do’ town of Bridport, I am confident that together we will make 2021 the year Bridport bounced back and moved on from Covid19.

LYME REGIS

Brian Larcombe, Mayor and Chairman of Lyme Regis Town Council

2020 has by any standards been unprecedented and challenging, and for those who’ve lost family members or suffered illness it’s been both heart-breaking and threatening. It has been a year of depths; the depth of what we have had to face, and the depth of personal and collective response we’ve all given to this unforgettable year.

Lyme and indeed the local radius have reason to feel more fortunate than other parts of the UK. We did a great deal in 2019 and much of this continued into 2020 despite Covid-19. It hasn’t been easy but there is now a better prospect ahead of us because of the efforts made over the last two years and throughout 2020 by everyone.

Although the effects of Covid will be with us in different ways for a long time yet, we have and will continue to adjust and adapt with the same resolve in 2021, with optimism and responsibility.

We should respect and maintain the physical distancing and other Covid measures required, and importantly cherish the closeness of those around us; the important things that may have been lost to the less important, and the things that this year has encouraged us to rediscover and value.

BEAMINSTER

Craig Monks, Chairman of Beaminster Town Council

2020 has been a very different and difficult year. During Lockdown, Beaminster Town Council implemented the Community Resilience Plan to support residents, businesses and local groups in such extraordinary times.

Through our website, our social media and an army of volunteers delivering leaflets, we aimed to up our game in communicating with the town. Most recently we have started to live stream our council meetings so residents can watch live or after the event. And lastly, we are now providing a monthly update in the Team News with news and useful information we wouldn’t want local people to miss.

After the initial lockdown, we had hoped for a return to some normality so we started our Beaminster Restart Campaign with the flags, bunting, flowers and of course the Scarecrow Hunt Competition, all aimed to welcome new and old faces back to the town. This year will see the return of many regular events such as the Beaminster Festival. But we have much more planned for our residents and visitors to enjoy. So we look forward to welcoming you back to our town soon. Just visit www.discoverbeaminster.co.uk to see what we have planned. The future is bright, but for now stay safe.

SHERBORNE

Jon Andrews, Mayor of Sherborne

After a very unexpected 2020, we welcome 2021 with open arms.

Our wonderful volunteer sector in Sherborne has stepped up and helped in so many essential ways, at such difficult times.

A community pandemic recovery fund has been established aimed at not-for-profit organisations such as locally registered charities, food banks and community groups who may struggle to survive or to meet demand in the pandemic.

The future economy and prosperity of Sherborne depends to a great extent on the wonderful variety of independent businesses in retail and hospitality. It is one of the factors that makes the town an incredibly special place to live and visit. Government financial support allied to the furlough scheme has been a lifeline to many. But the second national lockdown came at one of the busiest times of the year for small business owners.

A new website has been recently launched together with social media platforms making it easier to communicate with the town.

Looking ahead, the council faces huge challenges with pressure on budgets, but we are delighted to have been selected by the Dorset LEP to receive funding for the ShopAppy scheme that will take the high street in Sherborne online, bringing a great opportunity for shops to reach more people.

Blue Sky Thinking

The most popular New Year’s wish is that 2021 is nothing like 2020. Fergus Byrne has been hearing from some local businesses about how they see the next year unfolding

Looking into a crystal ball at the beginning of a new year we often hear talk of ‘million-dollar questions’ about the future. This year, it’s more likely to be ‘billion-dollar questions’ and it’s also more likely to be about years rather than the next twelve months. What lies ahead for the world economy, the national economy—and more important to most of us in this corner of the South West—what lies ahead for local business and the economy of our wider local community is a popular question.

Although for some, the impact of Brexit will be somewhat hidden by the impact of coronavirus, the double hit on the UK is enormous—especially when many businesses have never fully recovered from the 2008 economic crash. And while debate on the rights and wrongs of decisions made by government over the last few years and months will rage forever, this is where we are. So with hospitality and retail in the spotlight, we asked a few local businesses to tell us a bit about their hopes for the coming year.

Unsurprisingly, views are mixed. There’s is no doubt that for many there is light at the end of the tunnel, it’s more a question of how long that tunnel is—and for some businesses it is likely to be longer than for others.

Alastair Warren, chairman of The Electric Pub Company, a recently launched hospitality business in Dorset, sets a positive tone but echoes a point that many have voiced in recent years. He warns that if we don’t support local businesses we will lose them. Talking about the upsurge in online purchasing and the long term effect that that may have on his local town of Bridport he said: ‘It’s perfectly fine to buy things online, we’re all human beings and all looking for a bargain at the end of the day. But if you do that at the expense of going into RLK Tools or into Cilla & Camilla or the Morrish & Banham Wine Shop or any of the other independent retailers in town, eventually those retailers won’t be there.’

As the owner of the Electric Palace Cinema and a growing stable of pubs as well as a wine business, Alastair is aware of just how difficult trading has been in the last year for customer-facing businesses. ‘The last year has been about survival’ he says. He believes that in the main, government support for the sector has been good. Grants and furloughing have helped offset some of his company’s losses, and post lockdown trading in pubs like the Pymore Inn outside Bridport has also helped. But social distancing makes it very difficult for most pubs to trade. And with limited inside space, he sees a ‘difficult winter’ ahead.

However, looking further ahead he believes valuable and useful lessons have been learned on both sides of the counter from the way the industry has adapted. ‘We got an enormous amount of support’ he says of the way people came out to the pubs that were able to open. ‘And I think we learnt a lot.’ He cites ‘table service’ regulations and food deliveries as bonuses for customers that he describes as ‘much better in terms of the customer experience.’

So, whilst he hopes that by next summer we have ‘something that looks more like normal’ and that people will be able to walk up to the bar to order drinks, he thinks that levels of customer service will have improved. ‘We will continue doing food deliveries in a post-lockdown world because people like it’ he says. ‘We were forced to do exclusively table service; we will continue to do table service in those venues which can justify it, like the Pymore Inn and one of the others, in a post-lockdown world.’ Alastair wants to retain ‘the good bits’ as well as allow customers to ‘do all the things you used to be able to do—hopefully in a post-vaccine, normalised world.’

His business can be broken down into three categories: the cinema, the wine business and the pubs. All sides of the business were negatively impacted by the coronavirus lockdowns in different ways—the cinema perhaps worse than others. ‘I would say that cinemas and theatres are almost the sworn enemy of social distancing’ he says. He explained that when you go to a cinema or a theatre you typically are sitting very close to the person next to you and generally entering in through a crowded foyer, as well as mixing with people while getting drinks at the interval. And of course live music or theatre, involves interaction between lots of people, with the exception perhaps of solo comedy shows and cinema.

‘So, by definition, it’s very difficult to maintain social distancing’ he says. ‘That being said, we did reopen very briefly, to do the first part of BridLit prior to the current lockdown, and actually, it went incredibly well.’ Although only able to facilitate about half the normal audience, he said the event was very well supported. ‘People were incredibly understanding, in terms of how they entered and how they exited the building, how they pre-ordered their drinks, how they just operated responsibly. That has given us great encouragement.’ Encouragement enough to consider running a limited programme of comedy which he says ‘can be done because there’s only one person on the stage and then a spread-out audience.’ He hopes the same can happen with film, with the audience distanced.

‘What remains difficult, until such time as social distancing is removed, is live theatre and live music because you just can’t make the numbers work. You need too many people in the building to make a commercially realistic enterprise. But with the optimistic view that the government will have rolled out a vaccination programme to the most vulnerable by the Spring, and then with a view that the weather will be improving and there will be a more comprehensive roll-out of vaccinations through the summer, we are hopeful that we will be back to normal audience numbers by the summer period’.

Although that may feel like a long way from now, it shows a level of positivity that might give theatre goers hope.

Alastair is also investing in the Bridport Arts Centre building with plans for a restaurant, café and wine bar next year. However, although his wine retail business is doing well and he expects it to grow he says ‘I’m actually pretty cautious on retail generally because there has been this marked shift towards online.’ This is why he hopes people will make the effort to support their local independent shops and businesses. ‘You’ve got to be balanced about it’ he says. ‘I’m not saying buy everything in Bridport but I’m saying, spend money in town because otherwise the town that you love won’t be there and I think that’s really my message and that’s what I try to do. Of course, there are some things which I source from suppliers outside of town but the vast majority of things that we buy for our businesses, we buy from the local area and we recognise we have to sometimes pay a little bit more for that. But do you know what, customers, in turn, are also prepared to pay a little bit more for that. It’s a little bit everywhere, and doing a little bit to help everybody sustains these communities.’

Richard Barker from Cilla and Camilla is also upbeat about the future of our local community. Although hit hard by the lockdown, he saw better trading than expected when the first closure ended. ‘We had a wonderful summer’ he said. ‘We put that down to two things; people not going on summer holidays, so we saw an awful lot more visitors who were choosing to camp or come to nice hotels in Dorset rather than go to wherever they went otherwise. But we also saw a lot of people that might have gone and shopped in Exeter or Bournemouth or Bath or Bristol, who simply weren’t going.’

Many retailers and hospitality industry businesses had looked forward to November as a bonus trading period after losing the first months of the summer. But the second lockdown ended that hope. Kathryn Haskins from the Alexandra Hotel in Lyme Regis had seen November as a month when a little of the revenue from lost bookings might be clawed back. But it wasn’t to be. ‘We were looking forward to a really busy November and that all went by the board’ she said. The overheads of running a building like the Alexandra when there is no income is a massive challenge. No easing of business rates can cover those costs. Unlike the retail option of increasing stock and selling more products, the hotel industry sells time. ‘In a hotel, the rooms you’ve lost are the rooms you’ve lost, you can’t make up for it’ she says.

Tier 2 rules have not helped the restaurant trade either. ‘Not many people go out to eat with the people they live with’ explained Kathryn. ‘A lot of people go out to meet with friends and of course, you can’t do that, so all our lunch booking trade is just gone. People come to eat with friends and catch up.’ Alluding to the Government ruling she said, ‘So they’ve killed the business without killing it.’ However, no matter how hard it may be, she is fiercely determined to support her local community. As soon as lockdown lifted she and her daughter were out visiting the local shops. ‘We’ve done a binge in Beaminster and a binge in Lyme’ she says. ‘We’ve been waiting until the shops open to actually spend our money locally and I think a lot of people are doing that.’

That is one of the many positives that we hear from both businesses and customers, and not just locally. When the first lockdown hit, a national spirit of sympathetic support lifted the country. ‘I think it is great how positive people have been locally and how supportive people have been locally’ said Kathryn. ‘The messages we have had from guests and from all over the country and even from abroad have been so lovely. I’m hoping that that will continue into the time we reopen.’

That hope for a better year ahead, as 2021 moves into Spring, is echoed not only by those in business and their customers but also in the way some business owners are looking ahead. Mark Hix, whose restaurant chain went into administration in April 2020 as a result of the pandemic, has already reopened his original restaurant in Lyme Regis and has now taken on the lease at the Fox Inn in Corscombe. The pub had been bought by local residents Eva and the late Ray Harvey in 2012 to save it from being turned into housing and to preserve the hamlet’s history. Family friends of Mark’s for many years he explained, ‘When they offered me the lease, I thought it could be a great opportunity, despite these uncertain times that we are in. It will be my first pub, so it’s an exciting new project for me in the countryside where I’ll be serving local meat and game along with some British pub classics, a contrast to the fish and seafood offering in Lyme.’

Mark has many plans to help build up local trade while at the same time promoting other local producers. In the New Year, he hopes to host a Farmer’s market showcasing the best of the produce from the local area. ‘With all the challenges that we are facing now, it’s great to be able to focus on an exciting new project’ he said. ‘It’s important to me that I keep The Fox as a traditional local pub with great food and drink. Since lockdown in Spring the pub has only been open three days a week, so I am looking forward to opening six days a week for the locals and visitors to the area to enjoy once more.’

Listening to the thoughts of some of those in business locally, it’s no surprise that there are mixed feelings about the future of the local economy. Rebecca Hansford from the award-winning wine producer Furleigh Estate outside Salway Ash, saw an increase in trade as soon as the first lockdown ended. ‘However, there is no escaping from the fact that we lost our Easter and early summer 2020 trading period—a quarter of the year’ she explained. She also had to cut prices to keep cash coming in to pay vineyard staff.

Rebecca is also keenly aware of the impact that Brexit will have on her business. Most of her equipment comes from the EU which means servicing and parts will be a headache, as well as sourcing products such as corks and wirehoods which currently come from Portugal and France. Her company produces some of the best wine in England, but as she points out, cost increases are inevitable. ‘The issue for us is whether the wine drinkers of the world will pay the increased price this will mean for our wine. Still, C’est la vie!’

Alastair Warren has said that he believes customers will be prepared to pay a little bit extra to support their local community, and with reports of a likely hike in the cost of imported foods after December 31st—and this could apply to many products—his ability to look at a national or global view may be helpful. As a former senior executive at Deutsche Bank as well as at Goldman Sachs, Alastair is in the unique position to be able to look at the bigger picture, as well as the area he grew up in. ‘There will, I think inevitably be some economic cost to Brexit’ he says. Although he hopes it will be mitigated to a large extent by whatever deal is agreed with Brussels. But he believes it will also be mitigated by an increase in taxes. Regardless of whatever government is in power, he says ‘That’s the only way you can pay for it.’

But he also believes that the government will need to make people feel better, so hopes to see them ‘providing some kind of support or price guarantees for domestic producers which will be important around milk and other produce.’ He also suggests that the housing market will need to be assisted with an extension of stamp duty relief and other measures ‘because the housing market, in the south-east of England is still totally dead, pretty much, and that has a knock-on effect through the whole thing.’ He expects interest rates to remain low for a very long time and hopes also to see increased levels of support for ‘small and medium-sized businesses and the rural community.’

Unlike many who share dire predictions of a post COVID world, Alastair doesn’t expect a global meltdown. ‘I’m actually pretty optimistic about the global outlook’ he says. ‘I don’t see global recession, I actually see continued stimulus coming from a wide variety of governments.’ However, he believes much depends on the success of a vaccine. Speaking about the other businesses he runs he says ‘we are seeing pretty encouraging signs, albeit critically dependent on the vaccine becoming a reality.’

With his “investor confidence” hat on, Alastair offers fascinating insights into what we may expect from the impact of Brexit and the effect of the coronavirus pandemic on our future, but his keen business eye is also heavily focused on his local town and the wider community around it. ‘One of the great strengths of Bridport is the fact that there are very few chain stores in the town’ he says. ‘And we’ve got a small number of quite large private landlords who have actively encouraged independent retail for many years, and my understanding is that through this difficult trading period, they’ve actually been pretty flexible on rents and the like. So, I’m actually quite optimistic for Bridport because I think the landlords have acted responsibly. But I’m quite cautious about the market towns and larger retail centres where they don’t have that same feel and understanding. Bridport is quite unique in that sense.’

The retail market may look worrying after the collapse of efforts to keep Arcadia and consequently Debenhams alive, but both Alastair Warren and Richard Barker see that as something that was going to happen despite the impact of COVID-19. Arcadia ‘was over-levered and they hadn’t moved with the times’ says Alastair and ‘It’s not the pandemic that’s caused the problem. There was a problem already and this has just exacerbated it and brought the issue forward’ says Richard.

On balance, we may be fortunate within the Marshwood Vale Magazine’s wider local community to be somewhat shielded and less prone to the devastation that this last year has wrought on some parts of the country. But there is little doubt that challenges remain. And the one thing that can help to temper these potential difficulties is ensuring that we spend as much of our money in nearby towns and villages as we can, and support locally-owned businesses as a priority.

UpFront 01/21

The fact that this is the twentieth year that I have worked on our New Year’s issue was brought home to me by a customer I spoke to on the phone last week. He was in the process of winding down the business that he had built up over the last twenty years and pointed out that we both began in the same year. He recalled how we started our respective businesses in a time of turmoil—just after the 9/11 attacks in the US and against the backdrop of foot and mouth disease in the UK—and how the world was now in the throes of yet another crisis. It is hard to believe how many New Year’s resolutions have come and gone since then. And even harder to believe the level of uncertainty we face coming into another year. But I have looked back at some of those Marshwood Vale Magazine issues from the last twenty years and been amazed by how much has happened in this small patch of the UK. Apart from building a record of the people, events and sometimes the hopes and dreams of those that live here, I can see that, over the years, we have also captured a sense of the resilience and positivity of those that have helped build and maintain the landscape and economy of the area. Once a mostly agricultural community, changes in the way we work, the culture we create and enjoy, and the way we collect and consume our food, has meant the area is now made up of people from within a hugely diverse range of industries. The business from which the area derives its income has changed too. And although some may argue differently, that diversity has made us stronger; without hugely changing the heart and soul of where we live or the core thread of humanity that flows through our wider local community. And long may that be the case. By supporting each other, local businesses and the communities they serve can grow and work together and create a better future. In this issue, we hear from local leaders, local business owners and many others who are striving to make our world better. We will carry on doing our bit to keep highlighting and promoting them, and also continue to create a deeper record of the community we are part of. And although at a mere twenty years of age we are older than Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and all the other social media platforms—and thus a dinosaur in terms of modern communication—I think I can live with that. Besides, what would the Jurassic Coast be without its own dinosaur?

Marshwood People

A selection from past issues