One of the last live sporting events I attended was when Exeter Chiefs hosted Sale at Sandy Park in January. It was a disappointing result for the home team and a fairly mediocre game. But despite that, I doubt that I’m alone in wishing I could enjoy a live game again. I watched the Chiefs recent match against Leicester on television, and although there was some great rugby, without a crowd it seemed somehow hollow. Even the banter between commentators fell flat. And that’s an issue that has faced all sporting event organisers and clubs. Apart from the loss of revenue at the turnstiles, there is the question about how much fans will continue to be entertained by events on a screen. The need for some kind of atmosphere has led clubs across the world to try various different initiatives to bring their games to life, occasionally with hysterical consequences. One great story concerned FC Seoul, a South Korean football team. The club had to apologise to fans after ‘accidentally’ placing sex dolls dressed in football kit on seats in the stands in an effort to instil some atmosphere to their home game. While some clubs have tried using mascots, cut-outs of fans, portraits on seats and even dancing robots, FC Seoul purchased what they thought were shop mannequins to sit in some of their seats. However, as soon as the game began live transmission, the club was inundated with calls from people pointing out that the shape of the ‘mannequins’ made it very obvious that these were not for standard shop window use. The club was fined £67,000 and apologised, claiming that they ‘failed to make detailed checks’ on the mannequins. Rumour has it that afterwards they were inundated with applications for the role of Chief Mannequin Checker (CMC). Although some restaurants have trailed the idea of placing mannequins at empty tables to make their premises look livelier, the whole debacle did spark musings about where these shop dummies could feasibly be installed to replace humans. With Prime Minister’s Question Time sparsely occupied due to social distancing, one popular suggestion was to place them between members on the benches. The Speaker of the House could be given some kind of remote control system to make them (the mannequins) bray and guffaw on command. That way the House might get through more of its daily business with less interruption.

Candida Dunford Wood

‘I have always loved my Greek—or strictly speaking Vlach—heritage. Every woman on my mother’s side of our family has a gold arm bangle, and when I decided to remove it for reasons of security when I went to live abroad, this felt like more than a physical separation.

My father, Peter, was reserved, and very dedicated to his work. He and his brother were dispatched to England from Hong Kong for their education at the ages of five and seven. From that time until they were in their late teens they saw their father once every four years, and their mother every other year. My grandfather was interned in a Japanese prisoner of war camp, and miraculously survived. When he emerged, weighing six stone, he and my father’s greeting was merely with a handshake.

My mother Jenny grew up all over the world as her father was a Diplomat. She became well versed in several languages and briefly worked for M16. She became a painter.

After working in the Foreign Office in Cambodia and then Canada my parents came back to England and my father went into Politics, becoming MP for Blackpool South in the 1963 election, when I was two. As with many who lived through WWII, he was driven by a desire to avoid war, and he was involved in international relations. He was an MP for 30 years.

I remember a fierce argument with him and with my godfather Robin Day in which I stood my ground perhaps for the first time, by refusing to take the Oxbridge entrance exam. My reasoning was that it wasn’t the real world. However, I think I was also afraid of failure.

I took a degree in Ancient Mediterranean Studies at Bristol, steeping myself in that ancient culture, the seat of ‘democracy’ and ‘civilisation’; the mythology, the architecture. In those days we didn’t have to consider so carefully employment opportunities at the end of our studies.

Six months of travel to South America after I left University opened my eyes to a world unimaginably different to the safety and privilege of my own youth—one of injustice, exploitation and poverty caused by abuse of power, and this journey changed my life. I was struck by the irony that I could witness all of this because I had privilege: I decided to use this advantage as best I could.

Back in London, I chanced upon an organisation called ‘CARILA’—not realising this stood for Committee for Revolution in Latin America. I confidently marched through their door, naively believing my wanderings had taught me everything about the continent. I built up trust and helped them raise funds for art and crafts courses to be run by and for their communities of refugees. I went on to work with Chilean exiles, and through them learned about British politics, from their perspective. Their political prisoner internships had been commuted to exile under our Labour Government in the late 1970s. Most of them were professionals yet worked here in very menial jobs. Many of the women had not had a chance to learn fluent English.

Working for several years in ‘Christian Aid’s’ Latin America Department I then landed a five-year contract with ‘Oxfam’ in Brazil. There, I met many inspiring, courageous and resilient people who were battling to overcome poverty and injustice, with grace, humour, vision and determination. I worked with a team of Brazilians, travelling throughout the Amazon and the drought-ridden North East. We supported rubber tappers in negotiation with the World Bank for their rights to Extractive Reserves; radical catholic priests providing safe havens to activists and protecting indigenous lands; medical herbalists enabling poor people to improve their health; pioneers of rural technology; and the Landless Workers Movement who put their lives on the line trying to force much-needed land reform. I married José Karaja, who was given his name by the indigenous tribe with whom he lived while making himself scarce from the military dictatorship as a student.

Missing family and close friends, I returned to UK in 1994 with my half-Brazilian son, Daniel and continued working with ‘Oxfam’ in their Policy Department. I had an exciting job as Southern Advocacy Adviser but this meant travelling around the world for weeks at a time, leaving Daniel behind. So, I decided to base myself in the UK and to be involved in the local community around me, while maintaining an international perspective.

By this time, I was also exploring a different way of doing things. I believe information alone is not enough for people to change behaviours—we need also to feel and to experience the issue. The arts can help people to express themselves, to communicate and to build bridges, to create societal change. So, I decided to involve myself with arts for a social purpose.

I volunteered for ‘Artangel’ on a Legislative Theatre project with Brazilian founder of Forum Theatre, Augusto Boal, and his main UK followers. This led me to co-translate Boal’s autobiography and to manage Longplayer, an Artangel project devised by Jem Finer, a former member of The Pogues.

I threw myself into ‘Artists in Exile’, a group of over 70 artists in the London area, all of whom had fled war and persecution. Many had had to flee because of their artform, whether theatre, film, poetry, or literature. I witnessed how people could finally become visible and once again find their voice, having been rendered worthless in the UK. Everyone came together—Serbs, Croats and Bosnians, Colombians and Chileans, Iranians and Iraqis, Sri Lankans, Czechs and many more. Political boundaries melted away, and heart-wrenching performances were created, which were transformative both for performer and audience.

I founded Creating Routes with Hugh Dunford Wood, now my husband. We ran a series of programmes with artists who had experienced forced migration, whereby those artists ran courses for the public, sharing their considerable skills.

I founded ‘Creating Routes’ with Hugh Dunford Wood, now my husband. We ran a series of programmes with artists who had experienced forced migration, whereby those artists ran courses for the public, sharing their considerable skills.

Rewarding as this was, Hugh was missing the sea. So, in 2007, we decided to move to Lyme Regis where he’d lived before. My son Daniel’s life was transformed by joining B Sharp, which encouraged his love of music and to take a Degree in Theatre Sound.

I wanted to direct my energies to my new community. Inspired by Rebecca Hoskins who had turned her Devon village of Modbury plastic bag-free, I founded ‘Turn Lyme Green’ in 2007. Our ‘Plastic Bag Free’ campaign involved a wide range of community groups and schools, and was my first foray into community-led environmental activism.

I balanced this with my own exploration of permaculture, through a Design course at Monkton Wyld Court. This taught me to observe nature and how to create maximum yield maximise yield for minimum effort! It also inspired me to participate in Living Nutrition courses led by Daphne Lambert at Trill Farm. I’m delighted to have recently become a trustee of the ‘Green Cuisine Trust’—a charity founded by Daphne, which promotes food which is healthy both for people and the planet.

I co-ordinated the arts programme of the Lyme Regis Fossil Festival for a few years, and the Jurassic Coast Earth Festival linked to the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad. Then the opportunity arose to manage Communities Living Sustainably (CLS) in Dorset, which included programmes on Eco Schools, Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency, Climate Change Adaptation, and also ‘Food Future Bridport’.

Hugh and I recently moved from Lyme Regis to spend 18 months in Sussex on the farm of my childhood. This brought me full circle and enabled me to walk my talk in relation to ecology.

Together with my sister, we’ve converted the farm to organic, strengthened wildlife corridors, enhanced biodiversity, and taken measures to improve soil health. I am still heavily involved in the farm but we returned to West Dorset a year ago, finding a house on the edge of Bridport, surrounded by a sloping acre of rough grass. We can walk straight out to the woods, invigorated by the trees and the breath-taking 360 degree view from the top of Allington Hill. We’re growing fruit and veg and establishing a forest garden.

I love Bridport—it has the perfect blend of community engagement, local food culture, independent shops and a fabulous market, as well as a vibrant arts scene. I’m part of ‘Seeding our Future’s’ food security project to work with local farmers, growers and citizens to adapt to climate change. This has brought me back into contact with people I worked with during CLS, and helped me feel a sense of belonging and a part of what is going on in the town.

My immersion in the arts and creativity is vicarious, although in earlier years I did make mosaics. I am surrounded by Hugh’s prolific and colourful work, and our home is often buzzing with interesting conversations about arts and the environment. One of the things Hugh has taught me is that as well as seeking to play a part in creating a better world, we can also live joyfully! ‘Celebrate life’ is our motto.’

The Lit Fix August 20

Marshwood Vale-based author, Sophy Roberts, gives us her slim pickings for August.

Since the last issue, when we were just coming out of lockdown, I haven’t much changed my habit for slim reads. In these distracting times, I’m still attached to those short books which allow me to escape for an hour or two each day—something I can start and finish in the bath, or before I fell asleep at night—giving me a daily sense of achievement (and much-needed escape) in these otherwise bewildering times.

I have, however, found myself picking up more travel writing than usual, or at least books with a keen sense of place, which is perhaps a reflection of itchy feet. I’m also being drawn to food writing as I dream of eating oysters shucked on a Breton beach.

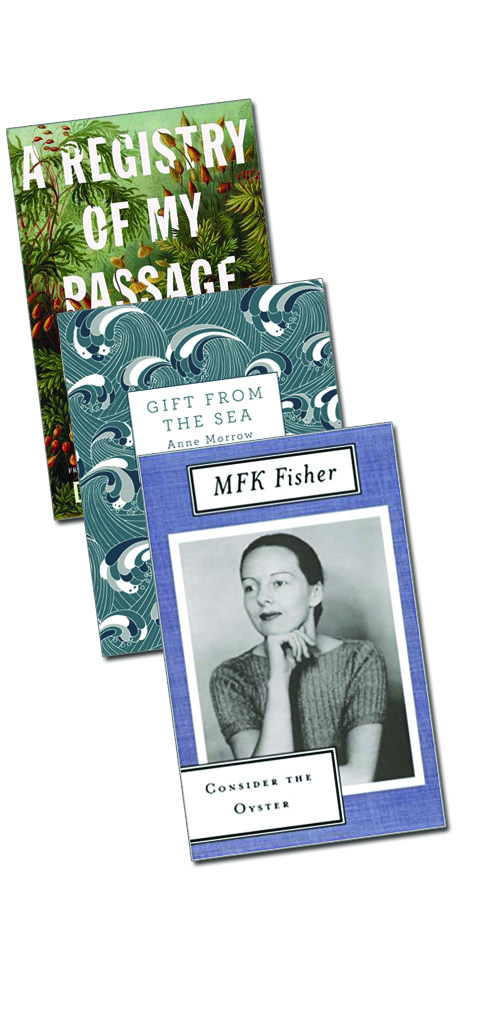

Here’s my shortlist of books for August—some short stories, a memoir and an ode to a mollusc (recipes included).

The Piano Tuner is an exceptional novel by the American contemporary author, Daniel Mason, about a nineteenth-century Englishman who travels to colonial Burma to fix up an instrument belonging to a Kurtz-like character in the jungle. Its themes, explored in this persuasive fiction, are not unlike Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. I was therefore quick to jump on the author’s latest: a marvellous new book of his short stories, A Registry of My Passage Upon The Earth. In it you will find a particularly moving tale about survivor’s guilt, told through the experience of a man who enjoys army re-enactments, and my favourite: a short story about the Dorset-born genius, Alfred Russel Wallace, a contemporary of Charles Darwin, whose work in biogeography led to Wallace simultaneously articulating the theory of evolution through natural selection. Mason’s writing is transporting, taking you deep into the thick of the Malay forests. Mason’s pen, so adept with fiction, gives spirit to the boundless curiosity of the scientist’s brain (Mason’s ‘other job’ is as a practising psychiatrist and a professor in the department of psychiatry at Stanford University, California). His Wallace story, entitled ‘The Ecstasy of Alfred Russel Wallace’ is also a prescient reminder to contemporary readers of the wonder of the natural world we are doing such a remarkable job of destroying.

Gift from the Sea is an essay written by Anne Morrow Lindbergh, a remarkably brave woman (despite her political muddles tarnishing her reputation) who ventured from Kamchatka to the Arctic with her husband, the aviator Charles Lindbergh. This 1955 instant bestseller records her solo retreat to a cottage by the sea on Florida’s Captiva Island. Using seashells as a means to anchor her meditative journeys, this book is a trove of insights about the necessity of both the near and the far in our lives, particularly among women. The far-flung can also be a difficult interior journey, she says: “We must relearn to be alone”. It is a phrase I have scribbled onto a note on my fridge, to remind myself about silver linings in the Age of Covid.

Optimism is a powerful emotion, especially in times like these. And if there is one thing that makes me salivate with appreciation for life it is the food writing of Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher, another American who commanded huge post-war celebrity. Her style is pithy, sensuous, and witty. Her prose weaves like the storytelling of an amusing friend you want to keep plying with wine. “To Mary Frances food was a metaphor for life,” observes the contemporary critic, Ruth Reichl (it was she who flagged up M.F.K Fisher’s writing to me, in an article published by an exceptional blog, lithub.com, which I recommend to everyone). As a small taster of Fisher’s oeuvre, try Consider the Oyster. It reads like an orison for a mollusc, taking us from docks of Marseilles to the gumbo stews of the Deep South, with recipes gleaned from home kitchens, shifty Russians and many more besides. I finished it as this column went to press, her writing leading me straight out of my door to Mark Hix’s new venture, HIX Oyster & Fish Truck, at Felicity’s Farm Shop on the A35, to stock up on supplies.

Sophy Roberts is a freelance journalist who writes about travel and culture. She writes regularly for FT Weekend, among others. Her first book, The Lost Pianos of Siberia—one of The Sunday Times top five non-fiction books for summer 2020—was published in February by Doubleday.

Help at Hand August 20

A psychological therapies service that is part of the NHS, Steps2wellbeing offers a range of therapies to help with mental health problems. In a series of short articles, Ellie Sturrock offers details of a vital community resource.

Low Mood and Depression.

We all know what it’s like to feel ‘depressed’ but actual depression is characterised by several symptoms that endure for more than two weeks. It can be recurrent and if a person has had three episodes of depression they are 90% more likely to have another one.

Lena is 26 and works in a local caravan park. She came over from Poland three years ago. Work has been difficult. She is not sure she is being treated as fairly as some of her co-workers. She is ‘stressed out’ she says and puts herself down. She is feeling low in mood and despondent.

Keith is 57, he lives locally and works as a plumber. He’s been diabetic since last year probably having gained weight after an injury at work that stops him cycling as he used to. Keith has had depression several times over the last 25 years. He has tried antidepressants in the past and some counselling. The antidepressants caused side effects and he described feeling ‘numb’ so he’s keen to try a different approach. Counselling was around a relationship problem and he is now very settled with his second wife.

He feels less confident about himself and is turning down social gatherings. He has been drinking alcohol more after work then wakes feeling sluggish and tired most of the time except at night when his mind races and he wakes in the early morning finding he is going over the past and worrying about his health and the family. He feels he is letting his wife down.

He heard about S2W and has had an assessment with a psychological wellbeing practitioner (PWP). She asked him about current problems and symptoms as well as past treatments and any risk, e.g. thoughts of suicide. She suggested he do an online web based course called ‘Lift Your Mood’ to treat his depression and after this recommended a relapse prevention programme called Mindfulness Cognitive Behavioural therapy; MBCT.

Lena also had an assessment with a PWP who suggested she do a seven session psychoeducational course based on cognitive behavioural therapy called ‘Overcoming Stress, Worry and Low Mood’. The PWP also made her an appointment to speak to an Employment Advisor (EA) who has special knowledge about employment rights. The EA appointments are offered by phone.

Steps2WellBeing (S2W) is an NHS service. You can self refer via the website (www.steps2wellbeing.co.uk), by email dhc.west.admin.s2w@nhs.net or by phone, 0300 790 6828.

This case is made up and is not a comprehensive case explaining all aspects of depression. To know more try leaflets produced by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk, MIND https://www.mind.org.uk or our website www.steps2wellbeing.co.uk.

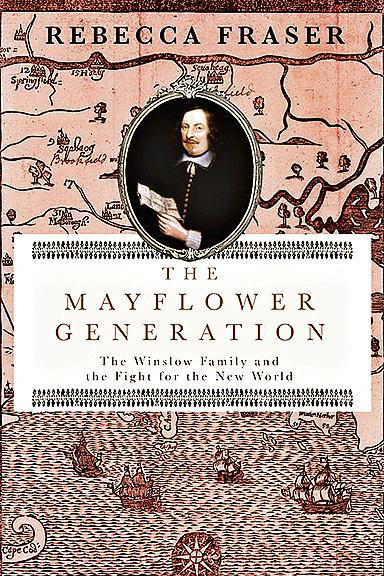

The Mayflower Generation by Rebecca Fraser reviewed by Bruce Harris

How many of the events planned to commemorate the departure from Plymouth of the Mayflower in September 1620 will actually happen in our present situation remains to be seen. It is to be hoped that as much of the intended programme which can go ahead will do, but for those whose knowledge of the event is sketchy, this book will be an invaluable aid.

Rebecca Fraser is a biographer as well as a historian, and her writing is people-led rather than dominated by dates and events, which gives the story a particular poignancy. While the venture had a very religious and political background, it is the extraordinary courage, determination and persistence of the people which is striking from the start.

The Mayflower pilgrims had already fled to Leiden, in Holland, to escape the oppressive religious atmosphere in England. The hopes of greater religious toleration invested in the accession of James 1 in 1603 had largely been dashed, and Puritan clergy were being widely ousted from their livings. When further difficulties began to arise in Holland too, over 100 of the Leiden English Puritan community sailed to England in a small boat called the Speedwell.

Their first attempt to leave Plymouth in August 2020 in both the Mayflower and the Speedwell failed because of the unworthiness of the Speedwell. The Mayflower, in truth, wasn’t much better – the ship was scrapped in 1624 – but if the expedition was to go ahead, the pilgrims had no other choice than to all pack in to the Mayflower, which was 100 feet long and 25 feet wide, a ‘bathtub with masts’. After a profoundly difficult and uncomfortable two month voyage, 102 pilgrims and 30 crew landed on the coast of New England in November, probably the worst possible time to arrive. Half of the pilgrims died during the first winter, and the colony would have been wiped out altogether but for the help of the local Indians.

Central to the success or failure of the expedition was the Winslow family, originally yeomen farmers turned cloth merchants In Droitwich, near Worcester. Edward Winslow became the Governor of the Plymouth Colony, and he was a fascinating and in many ways admirable character whose abilities are adeptly illustrated by Fraser. The persistence and courage of the community in the teeth of dreadful obstacles and a death rate, including some suicides, which would have totally destroyed the morale of lesser people resounds through the story, and at the centre of it all is Edward Winslow, whose negotiating skills and ability to deal successfully with the local Indians gradually improved the colonists’ chances of survival. He established a relationship of trust and mutual respect with the prominent local Indian chief Massasoit which literally rescued the expedition from oblivion.

During the Commonwealth regime of 1650-60, Edward spent some years in England working in senior governmental positions. However, the Restoration changed the situation radically, and Charles II eventually imposed direct government on the New England colonies, which had become used to considerable autonomy. The new government also no longer recognised the Indian wampum shell-currency, meaning the Indians could no longer pay for the English goods they wanted, particularly the tools. Over the years, this also meant the only way the Indians had of paying their debts was by selling their land.

Edward’s son Josiah and Massasoit’s son Metacom, the latter’s name anglicised to Philip, were different characters from their fathers. Josiah had similar organisational and leadership skills while lacking his father’s careful diplomacy and respect for the Indians. Philip saw that the only possible conclusion to the way things were developing would the total subjugation of his people to the English, meaning the loss of their lands and their way of life. In 1675, he achieved an unprecedented union of the tribes, whose combined strength still heavily outnumbered the English, and a vicious conflict which has become known as Philip’s War broke out right across New England and almost brought the colonies to their knees before the Indians were eventually defeated.

We all know the outcome, and while we can respect the colonists’ determination and achievements, there is little to celebrate in the treatment of the indigenous peoples. As the years passed, the original uncompromising Puritanism of the settlers became increasingly diluted with the many and various adventurers escaping the persistent sectarianism of the British Isles. One of the great tragedies of the United States was that, while they sensibly managed to avoid the vast religious conflicts of Europe by setting themselves up as a secular state, they found another issue which would tear the country apart in slavery.

Rebecca Fraser follows the lives of the original pilgrim families until the early eighteenth century, and it is an extraordinary story made all the more remarkable by the author’s diligent and detailed handling of her material. Bearing in mind that these are, in effect, the years when our people gave birth to the nation which was to become the richest and most powerful in the world, it is surprising how little many of us know of them, and I don’t exclude myself from that. Whatever its merits and faults, this story is part of our story.

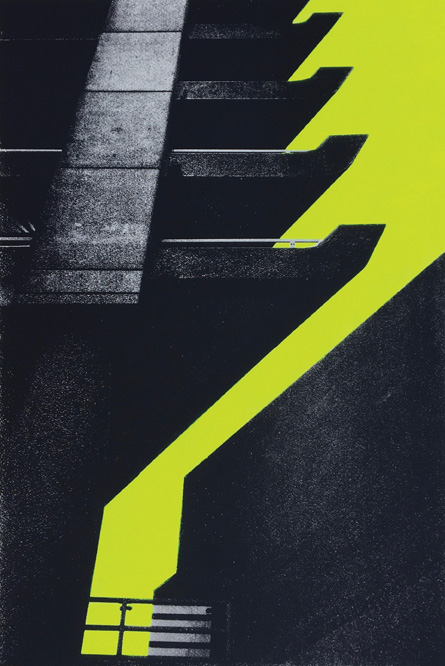

Angles of Inspiration

Devon artist Richard Kaye talks to Fergus Byrne

Despite there being no shortage of ‘lockdown’ blogs on the internet the full results of the last few months of enforced isolation will probably take decades to unravel. In the early days, with a rush of enthusiasm, many people predicted an enormous surge in creativity. There’s no doubt that happened for a lot of people, however many writers and artists who had expected an opportunity to produce volumes of work were surprised to find that wasn’t the case. Some writers particularly found it difficult to be creative and the same story came from many artists and makers. That expected burst of creativity just didn’t come—not for everyone anyway.

However, Ottery St Mary based artist Richard Kaye is one of those that found the process productive. As a print-maker, with no access to the machinery, he needed to produce his work he had a change of focus and a welcome return to painting and drawing. ‘Painting and drawing tend to be the go to mediums for artists in that situation’ he said. With the studio he uses in Exeter closed he wanted to work in a medium that was naturally comfortable to him. He wanted to be quickly up and running instead of thinking too much about any complex working structures. ‘I wanted something that was going to be simple to get straight into the creative zone with,’ he said ‘so I picked up some canvases and brushes and that was something that I could start making marks with straight away, whereas with something like a screen-print, it’s much more planned.’

For Richard that immediacy allowed him to explore and develop a theme of abstract landscapes that he had already been working on over the last few years. Some of it was work he showed in his last exhibition but realised they weren’t actually finished. ‘So I carried on painting on top of them for a while’ he explained. ‘I would say most of the painting work reflects the local area. All the paintings I have done are very similar in that the subject matter is abstract landscapes that take on that cubic geometric form, with quite bright colours and a subdued greeny-blue sky feel – quite a tranquil sky.’

Despite being more urban the landscapes complement the other work he will be displaying in an exhibition at The Malthouse Gallery in Lyme Regis from mid-August. A fan of Brutalist Architecture, Richard also recently completed a small series of drawings focusing mainly on stairways. These images tend to be very bold and distinctive, with some of the more urban subjects being somewhat unexpected. Richard takes pleasure in finding strong compositions and angular forms within subjects which are often missed or ignored. Turning these images into highly detailed and intricate prints was the basis of his introduction to printmaking.

In the last few year’s Richard has started to work on a larger scale, with screen prints which he hand-tints using watercolour. The colours he is using now have moved away from the more subdued pastel tones toward a brighter complementary range as well as neons. These images are really angular, edgy and bold. The neon ones even inspired Richard to start a streetwear clothing brand ‘2_Brutal’.

Trained at Bournemouth College of Art, Richard has had a varied career that has occasionally veered away from art. Apart from a stint as a chef at the Alexandra Hotel and time making false teeth in Axminster he also spent a year as a DJ travelling the world with Indie band Ash. ‘But the one thing that’s run through my career is my need for creativity in some way shape or form, whether it’s art or music’ he said. ‘Art has always been there. I’ve had periods where it has slowed down but if I had to go on a journey there’s no way I would go on a train without having a pad and pen with me. I’d walk up and down the train looking for people who’ve fallen asleep and I’d use that as an opportunity to do a life drawing.’ He has a series of drawings called ‘sleepers’ that he hopes may fit into the upcoming exhibition.

The upcoming show at the Malthouse Gallery, though varied in medium, clearly shows that he has a love for strong compositions and compelling use of colour. Following on from his first very successful show at the gallery in 2018, this sees a growth in confidence and a very refreshing show with striking architectural emphasis.

VJ Day 75 by Derek Stevens

Victory in Europe day was celebrated with teas, games and running races at Alhallows school in my village of Rousdon, where I had spent the war years with my mother and grandparents. Three months later I was visiting an aunt and uncle in New Barnet who lived right next to the railway station from which I could note passing locomotives enabling to underline their numbers listed in my Ian Allen book, the ABC of L.N.E.R. steam engines. It was that morning of August 15, 1945 when my uncle shouted up to my bedroom “Derek, the war’s over!” He then took me on a tour of street parties where everyone seemed to be singing “Roll me over in the clover and do it again,” leaving my eleven-year-old mind to wonder whether it was really as rude as it sounded.

The period since the Allied victory in Europe had seemed uneventful. The Pacific wars were far away on the other side of the world, but our attention was certainly re-focussed upon it with the announcement of the dropping of not one, but two devastating atomic bombs immortalising the names of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, vaporising most of their population. It has since been estimated that over a quarter of a million souls perished in the two attacks.

Life at home continued unchanged, grey and somewhat austere. Additional cuts were made to food rationing which was to continue for another nine years. For the first time bread was rationed because there were millions to be fed now in a devastated Europe, much of which had been destroyed by persistent Allied bombing raids. Each raid had cost a million pounds and more, and the continuous programme of nightly raids flown by RAF Bomber Command during the latter part of the war had contributed greatly to the country’s final state of bankruptcy.

White bread, as we used to know it, suddenly became darker in colour and more coarse in texture, but a great reintroduction by our Musbury baker was a split penny-bun with fake cream in it. A speciality for Fridays only, it was something to hurry home for. New delivery men began to appear as servicemen became demobilised and returned home. Local ‘Devon General’ and ‘Southern National’ bus services were reinstalled, and the Royal Blue long distance coach would pass our front gate as it renewed its daily journey along the south coast to Penzance.

At this time of austerity, an action by the British authorities was to still rankle among the villagers of Dunkeswell. At the departure of the US navy from their airfield, from which they had been operating alongside RAF Coastal command in the task of Submarine hunting in the Battle of the Atlantic, to return to the United States, they had to dump much of what they had in store including food stuff. Permission from the British Ministry of Food to offer it to the local population was refused, so sacks of sugar and sides of bacon were among some of the foodstuff which had to be incinerated by order of His Majesty’s Government.

A wartime hero, who could be found selling his catch by the roundabout on Seaton seafront, was fisherman Tom Newton. Walking out of his front door from his house alongside the river mouth at Axmouth he was alarmed to see a naval mine freely drifting upstream towards the bridge. Fortunately, he later recounted, it was attached to seven fathoms of cable impeding its progress Thinking “I’d better do something about this” he grabbed an oar and waded out to the mine and started prodding it until eventually, with the help of a turning tide, he managed to isolate it on a spit of shingle. Whereupon he called for the Royal Navy’s Bomb Disposal Squad.

They arrived with the news that the situation was a bit concerning, as there was a train load of naval ammunition in the sidings of Seaton station on the other side of the bridge due to be taken to Beer quarries for secret storage in Beer stone quarries.

Relating his experience sometime in the sixties he summed up by telling me that he was awarded the British Empire Medal by the King at Buckingham Palace, the town had had a whip round for him and the Navy “Gave me five pounds”. The red defused mine casing remained a feature on the riverside bank of shingle against the rusting tiers of anti-invasion scaffolding for several following years.

To supplement the scarcity of food at the time, standing spaces were at a premium on that old concrete bridge during evenings and week-ends as people gathered, shoulder to shoulder, tying to catch some bass or pollock on incoming tides.

Mass ownership of the motor car was yet to come so every weekend day-trips from Waterloo would arrive at Lyme Regis. Train loads of people would cascade down the hill to roam the town and sea-front for a few hours, then at about four-o’clock they would all be seen labouring back up the hill to the station to return to London. They were probably hauled back to Waterloo Station by one of the new merchant navy class locomotives, streamlined monsters rumored to thunder down Honiton Bank through Seaton Junction at 100 m.p.h. The Southern Railway was soon to be nationalised and incorporated into British Railways by a Labour government. The first election in post war Britain ousted wartime leader Winston Churchill as premier, with an unexpected landslide victory by Labour leader Clement Atlee. The newly elected majority government immediately set about establishing the foundation of the welfare state which we enjoy to this day.

A letter to my father in London at the time told him that a remaining piece of wartime detritus drifting in the channel, yet another old naval mine had drifted into Lyme Regis and exploded, “Many windows throughout the town had been broken in the blast”. At about the same time a large tank landing craft in transit along the bay broke down and was washed up on Seaton beach near the river mouth where the remaining storm broke its back. The navy towed away the section housing the engine leaving the forward section stranded to be taken over as a playground for local children. The old sewage pipe entered the sea close by, all before the days of Health and Safety awareness, the only casualty being the late “Topper” Tolman who broke a leg when he fell over the side of the vessel onto the beach. The remains of that old LST can still be seen beneath the waves a short way offshore I am told by local scuba divers.

Warners holiday camp at Seaton was reopened, having served during the war years as an internment camp during the early years of the war and a US Army base during the run up to D-Day. And the placing of a small colony of caravans on neighbouring ground laid the foundation of the future Blue Waters camp where Carry On Star Barbara Windsor and her gangster boyfriend, Ronnie Knight, bought two chalets for a seaside retreat. That area of happy bye-gone days is now covered by a vast Tesco and new homes.

German POW’s were delivered to surrounding farms from their camp at Tiverton, returning at day’s end. 24,000 elected to stay in the UK, the rest were eventually repatriated in 1948. Some returning home with thankful and fond memories of the friendly treatment they had received during their imprisonment.

One exciting picture of the world to come I remember was the announcement of the forthcoming streamlined British motor car. We had all been wowed by those super-duper streamlined cars driving high-ranking American officers about the country, now we were to manufacture one of our own, the Standard Vanguard. I was to pass my driving test in one of these vehicles during my time in The RAF. National Service was the general direction for school leavers at the time rather than a university campus. Also, for the more adventurous one could have joined one of the several colonial police forces existent at the time in Kenya, Rhodesia, Malaya, Hong Kong and Palestine being among them. Palestine was a particularly nasty area of operation at that time, the rest representing the dying embers of a once dominant world empire.

Returning from my visit to Barnet I found we had bread and breakfast visitors staying. My grandmother had found the old CTC (Cyclist Touring Club) sign in the bike shed and had re-erected it outside the gate.

I got myself ready for a new school, I had passed a scholarship for Lyme Regis Grammar school. Playing in the field alongside, we could see the corrugated iron remains of the old shelters falling into the ditches beneath the hedges where they had been built five years previously. Catching the train, ‘Lyme Billy,’ from Combpyne to Lyme Regis every day, the rule was first-class compartments for girls, third-class for boys.

Another new boy joining at the time was Major T.B. Pearn who had participated in the Arnhem landings and had now become our new headmaster. He was especially musically inclined and soon had the main hall resounding to the whole school belting out the words of ‘Jerusalem’.

The Internet of Things

As we all continue to emerge from isolation, it’s really great to be able to view real people and real places again. We’re like a troupe of bears slowly shuffling out of our winter hibernation and rubbing our eyes with the brightness of the light and the green countryside all around us. I don’t know about you, but I reckon we’ve all learnt quite a bit during the lockdown, and because we couldn’t go anywhere or meet anybody for four months, we’ve been exploring the only area that was truly open to us—the internet.

With all that spare time, I have now discovered websites that I never knew existed. I have played loads of computer games with my children and learnt humility and how-to-lose comprehensively. I have watched endless BBC news headlines but have also widened my global view by downloading news and opinion in English from non-UK websites like Russia’s Pravda, Singapore Straits Times, the South African Herald and China Today. The Pyongyang Times website from North Korea is worth a giggle or two provided you don’t actually believe a word it prints.

Yes, there’s a lot of garbage out there but there are some worthwhile gold flakes hiding in the internet’s cobwebs if you can find them. I have relived my childhood and streamed wall-to-wall old movies, zoomed through various Broadband quizzes and even tried to learn a new skill or two (card-tricks and poetry). In the course of which I have also purchased loads of online stuff that I never knew I wanted! Yes, you can really buy or experience just about anything over the internet if you want.

Here is my lateral guide to some online websites that might be useful in these post-lockdown times. You don’t have to click on any of them because they don’t exist. But I feel that some of them should exist and perhaps someone might launch them online someday…

www.ripOff.food will supply literally any vegetable from all over the world – even things that don’t really exist at all such as Siberian Eel Grass, Game Of Thrones Lettuce and Arctic Pepper. It’s all 100% organic and reassuringly expensive. Based in Azerbaijan, the cost of delivery is over ten times the cost of the food itself, but presentation is everything. Your handpicked delivery of Fresh Dragon’s Spittle will arrive in a Yak-driven Siamese cart lovingly packed inside a sterilised anti-Corvid organic balsawood coffin. Enjoy…

www.esperanto.lingo is an entirely pointless language learning website based in Germany. You could spend hours every evening at home learning Esperanto, but since nobody else speaks it nowadays you would be better advised to learn about basket weaving, Japanese sword design or breeding Mongolian catfish—all of which might be more useful to you in the future.

www.getStuffed.org is for anyone wanting to learn about Taxidermy. All your friends can bring you their favourite pet cat, hamster or canary so you can deliver back to them a lasting memento of their dearly loved departed animal. Use your time constructively and become a qualified taxidermist in lock-down. Launch yourself on a new career! Also works with reptiles, rats and goldfish. Avoid stick insects as they’re a bit thin and fiddly.

www.misterCloggy.co.nl is another of those instructive websites to teach you new and useful skills while you’re isolating yourself at home. This website has diagrams and instructions for you to learn how to make wooden clogs for your feet. Simple, useful, organic and good for the planet, you can pretend you’re a Dutch tourist on holiday in Chard. Warning: it takes about two years to carve and polish each wooden shoe, so you’ll need to be patient to get both feet covered.

www.virusVanish.co.ru is a Russian based website that downloads an infra-red anti-viral ray gun to your phone. Simply point your mobile at any passing virus (if you can see it) and ‘ZAP’—it’s gone! Warning: also kills passing birds, dogs and small children. Not to be used anywhere near Salisbury.

www.virtualMaskerade.co.xyz will download a virtual mask to you on those annoying occasions when you need to enter a shop and you’ve forgotten your own personal mask. Made from light tissue paper and spray-on black paint, it makes you look like you’re wearing a mask when in fact you’re not. If you hate wearing a real mask because it’s itchy and uncomfortable and makes your glasses steam up, this is for you! It’s entirely non-hygienic and has no effect on blocking anything, so from a safety point of view, it’s probably best to avoid.

www.socialdistanz.org is an app for mobile phone and PC that sounds an alarm if you get closer than 2 metres to anything. It is extremely loud and goes off every couple of seconds as you walk around town. Lamp-posts, traffic lights, abandoned rubbish, passing cars and other pedestrians will all activate the alarm making it extremely annoying and completely useless. Avoid at all costs. Do not install.

The Tolpuddle Six

To the north-east of Dorchester the River Piddle meanders, giving its name to several villages, including Tolpuddle, a pleasant village, which has been bypassed, enabling through traffic to avoid it. Normally an annual Festival takes place in Tolpuddle, when it becomes busy, but this year it has been cancelled. The Festival commemorates the story of six local men who lived there in the 1830s.

The story began after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 when soldiers were no longer required and therefore were looking for work. At the same time grain prices were low, resulting in farmers facing ruin. The Government introduced the Corn Laws aiming to help farmers, but the result was that the price of bread increased. Farmers kept labourers’ wages low and introduced threshing machines to aid productivity, which reduced the number of workers. This led to some frustrated labourers vandalising these machines, setting fire to ricks and throwing stones through farm windows. These actions commenced in Kent and spread across the land. The men involved were called “machine wreckers”.

Mary Frampton kept a Journal in 1830 describing her concerns about the rioters. She corresponded with another Dorset Diarist, Fanny Burney, who commiserated with her about her worries about the rioters. Mary Frampton had a brother, Squire James Frampton, who was very outspoken against the rioters.

In Tolpuddle labourer George Loveless, who was also a Methodist lay preacher, grew concerned when farmers promised they would raise wages to 10s a week, but in fact reduced them to 8s. When wages were dropped again to 7s a week, he decided to act. A meeting was held in a cottage lived in by Loveless’s brother-in-law, Thomas Standfield. About 40 labourers agreed to form a “Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers”. The society was to be the Grand Lodge of other groups in Dorset, with a secret password “Either Hand or Heart”. Their rules included that they should withhold labour if a master reduced wages or “stood off” a man for belonging to a union. Unfortunately they agreed to initiate new members by a ritual in which recruits were blindfolded, shown a picture of a skeleton and had to kiss the Bible and swear an oath not to reveal activities or membership of the society. Perhaps this ritual was a parody of the Masonic tradition.

Early in 1834 Squire James Frampton was given information by another labourer, Edward Legg, about the oath taking. Frampton took this very seriously and arranged for the six ringleaders to be brought to trial. An Act of Parliament in 1797 decreed that any trade unionist administering a secret oath was infringing the law. The Tolpuddle labourers were unaware of this when they took their oaths, as they later protested at their trial charged with breaking the 1797 Act, which was a felony punishable by a maximum of 7 years transportation.

The six were George Loveless (age 37), James (brother, 25), Thomas Standfield (brother-in-law, 44), John Stanfield (son of Thomas, 21), James Brine (20) and James Hammet (22) who have become known as the Tolpuddle Martyrs.

They appeared for trial at Dorchester Crown Court on 17th March 1834 before a newly appointed judge, Williams, who did nothing to help them. The judge was alarmed by the growth of rebellion and trade unionism, as was the Whig government, and in his summing up he told the jury of 11 yeomen and one farmer that if trade unions continued they would “ruin masters, cause stagnation in trade and destroy property”. The jury returned a verdict of “Guilty” in twenty minutes. The judge admitted that the accused had been previously of good character, but he imposed the maximum sentence of seven years transportation.

Soon protests were made against the sentence, in the national newspapers of the time. (However despite national petitions and a large public demonstration in London, the government would not reduce or cancel the sentences). All six convicts were sent, in chains, to join convict ships to Australia, to an even harsher life.

George Loveless was sent to Tasmania for a week in a chain gang, road making. Then he was transferred to become a shepherd and stock keeper at a government farm, which was a little better, but still harsh, sleeping in a hut, with a leaking roof and five beds for eight men.

The five other labourers were shipped to New South Wales and were marched in chains through the Sydney streets and then allocated to different farms.

James Brine had a very hard time as he had to walk thirty miles alone to his allocated farm. En route his belongings were pilfered by thieves who stole his belongings, including the bedding, blanket, shoes, new breeches and some money with which he had been provided. He reported to the farmer he had been allocated to, but the man refused to believe his story and abused him as “one of those Dorset machine-breakers”. Consequently James had to work for six months without boots. When digging post holes he found a piece of hoop-iron and tied this to one foot to help take the hurt of the spade.

Thomas Standfield, the oldest of the labourers was set to work as a shepherd, and suffered terribly working day and night at lambing time. His son, John, was allowed to visit him by his more considerate farmer several times as his farm was only a few miles away and said that his father was “a dreadful spectacle, covered with sores from head to foot and weak and helpless as a child”.

In April 1834 a large demonstration assembled at Copenhagen Fields near Kings Cross in London. They marched to Whitehall and delivered a petition to the Home Secretary, Lord Melbourne. However the Government would not cancel the sentences.

Finally in March 1836, after two years of petitions and lobbying from sympathisers, a new Home Secretary, Lord John Russell granted a free pardon to all six men. There were difficulties of communication and bureaucratic delays. George Loveless arrived back in England in June 1837. Nine months later four of the others arrived back. The last man, James Hammett, was not home until August 1839, over three years after the pardon was granted. He had not been at the oath swearing ceremony, but had been arrested in mistake for his brother John.

James Hammett was the only one of the six who settled back in Tolpuddle. He died in the Dorchester Workhouse in 1891, aged 79. He is buried in Tolpuddle churchyard and has a headstone carved by Eric Gill which reads “Tolpuddle Martyr: Pioneer of Trades Unionism: Champion of Freedom”. At the Tolpuddle Martyrs’ Festival a wreath is laid on his grave every year.

The other five eventually migrated to Ontario, Canada and of these John Standfield became a successful hotelier and for a time became reeve (mayor) of East London, there.

Some of the information produced here came from A History of Dorset by Cecil Cullingford. The old Dorset County Court in Dorchester High West Street has been renovated as the Shire Hall Historic Courthouse Museum and some of the cells are available to view, with relative information.

So this is the story of the Tolpuddle Six, or Martyrs’ and their eventual release and pardon and explains why normally there is an annual Festival, with a procession through the village, live music, and various stalls.

This year the Festival was organised as an online event over the middle weekend in July, with the following comment: “Tolpuddle .. represents the value of Solidarity, of joining together for the common good, something we all need to see us through this present crisis”

Tolpuddle is a pleasant village. I have a happy memory of visiting with my wife, daughter and son-in-law and sitting on a convenient seat under a shady tree, quietly, but not on a Festival weekend.

Cecil Amor, Hon President of Bridport History Society.