Interview by Seth Dellow

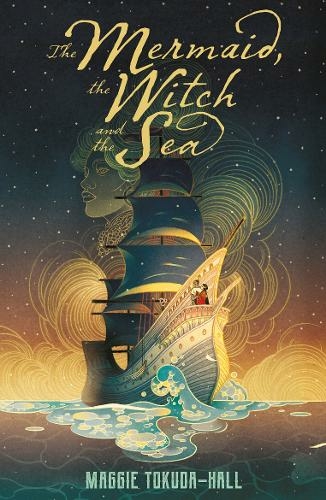

The Mermaid, the Witch and the Sea by Maggie Tokuda-Hall

What would you do to survive?

That is the question that Flora must answer with a blade as she secures her place among the pirates.

That is the question that Evelyn must answer with her empathy and wits as she seeks to escape the pirates’ treachery.

The only child of high-ranking nobles within the Nipran Empire, but with the disappointment of being born a girl, Evelyn has everything she money can buy. Unfortunately, money cannot buy the love, respect or affection of her parents. To her father she is an annoyance, to her mother: an embarrassment. As her family fortunes falter her value remains, in a land of high-stakes politics Evelyn has value as a pawn in marriage. For years Evelyn has pitied the ‘casket girls’ setting sail to unknown lands and unknown husbands, never to return—their worldly possessions transported in the very caskets they themselves will be buried in upon their deaths. Now she is to be one of them, leaving the cold comfort of home to the frightening savagery of the Floating Islands.

Orphaned and alone, Flora and her brother must steal to eat in the back alleys Nipran’s capital city. Their luck finally changes when they find work on a pirate ship, but in order to gain their places Flora is forced to prove herself by way of murder. And to maintain their places the girl must become a man, and Florian is born, for the pirate ship conceals its deadly purpose as a Slaver behind the veneer of a luxury passenger vessel.

As Evelyn sets sail on a luxury vessel, her destination—the military commander husband she has yet to meet—she is waited on by an interesting young cabin boy by the name of Florian. During the voyage the two young people begin to see past their class differences and make their way towards becoming, first friends and then their friendship deepens into something more. But Florian is treading on dangerous ground, he is a slaver and she is his prey, whether she knows it or not. If the crew were to ever discover his true feelings he would be in as severe danger as she and the moment of betrayal cannot be averted.

As we delve deeper into the world of Mermaids and Witches and the omnipresence of a sentient Sea we learn more of the depravity of the pirates—their lust for Mermaid blood, the drink that takes them to oblivion and allows them to forget. But the price for this horror is high, they too are hunted and not just by the Sea, and Florian’s brother has fallen foul of this self-inflicted curse. We learn the ways of Witches—eradicated throughout the empire to be sure, hunted and burned but surviving themselves, hiding and helping both those deserving and those willing to pay. And we learn the ways of the Sea, immortal and omnipotent, taking care of her own and helping those who care for her. As Evelyn and Florian interact, first with each other, then with the Mermaid, the Witch and the Sea their true worth emerges, to each other and to themselves.

In a dazzling display of world-building Tokuda-Hall sets the adventures of Florian and Evelyn against the background of an intoxicating, Japanese-fusion landscape. Weaving myths and legends from across continents, this is a harsh, brutal and ultimately beautiful tale of love, resilience and redemption. Blending gender fluidity, race relations and comparative morality into a rollicking fantasy adventure, Maggie Tokuda-Hall has created a modern fairy tale for our times. Absolutely brilliant.

Full disclosure—Maggie is a friend from my San Francisco bookselling days. he’s always been irritatingly talented (we were direct competitors!) but her debut YA novel puts her in a class above. A truly magnificent achievement from a truly wonderful soul.

The Coal Barge and the Jewel Anemones

Cunard’s Queen Mary 2, the world’s fastest cruise ship, has been laid up in Weymouth Bay since March, alongside several other such vessels. Massive on-board generators have to be kept running, though at reduced power. Fumes from their giant funnels spread and settle in a brown pall over the bay and its crowded beaches.

The release of pent-up psychological pressure was felt everywhere along this coast as the lockdown was eased. Erratic driving, massed revelry on beaches, piles of trash left behind. The imagery from all this stirred readily into the febrile news mix. The sea and what it means to us, the uses we make of it, even in a pandemic, are never far from view in a place like this.

The beer cans and the behaviour were still swinging in and out of the headlines when a review appeared making the case for HPMAs around the UK coast. Environmentalists love to wrap their doings in impenetrable acronyms. Perhaps they feel it lends them a professional mystique. They can perhaps hardly complain then if the public pays no attention.

There are at present no HPMAs of significant size anywhere in UK waters. That matters because HPMA stands for Highly Protected Marine Areas—i.e. areas where there is no fishing or extractive activity at all. A better name for them would be Really Protected Marine Areas, as distinct from the Not Really Protected Marine Areas, in which our seas abound. That distinction has of late been exposed even more starkly than usual. Difficulties in mounting patrols during lockdown made it harder to track vessels and led, predictably, to illegal fishing, in the Cardigan Bay ‘protected area’ and elsewhere.

Lyme Bay is home to a rare success story in all this. More than 70 square miles of it have been closed to all towed gear (scallop dredges, beam and otter trawls) and this ban has held since 2008, with rare incursions resulting in heavy fines. The sea-bed’s recovery has been closely studied by Plymouth University. The reserve is managed by a coalition of inshore fishermen, biologists and conservation bodies—Blue Marine and the Wildlife Trusts.

But even inside this area, potting, trawling and recreational fishing are still permitted everywhere. A recent report from Plymouth University, undertaken in collaboration with fishermen, has explored the impact of potting on the sea bed. It isn’t always zero. As the first, most successful and best-studied of the UK’s larger Marine Protected Areas, it is the obvious candidate to build on this achievement by closing part of it to all fishing and then watching what happens.

It’s worth recalling that the partial protection it now enjoys was fiercely resisted by government and industry lobbyists, on the grounds that it ‘wouldn’t work’. It manifestly has worked. The present abundance of skate, bass, cuttlefish and John Dory in Lyme Bay speaks for itself. The sea-bed’s recovery has been rapid and spectacular. What has happened here is just what industry lobbyists told us never could.

Therein lies its significance for all our coastal waters. With fewer of us travelling abroad this summer—however traumatic the reasons—might this not be a time to pay less attention to scuffles on beaches and more to reviews into HPMAs, whether or not such reviews made it onto your Twitter feed?

The relationship of our offshore habitats to the wider culture generally and the media in particular is not as often or as carefully examined as it should be. Two short years ago much was being made of Blue Planet 2. The programme reached a vast audience around the world. It seemed to be television at its best, although some in the UK criticised the series for dwelling too much upon seas remote from Britain.

Problems on this scale cannot be solved by one broadcasting corporation, let alone by one presenter or his team. It is surely up to every coastal community to be continually re-inventing its relationship with the sea. The area around Lyme Bay is in some ways peculiarly well-suited to this, and not just for the reasons I’ve already given.

The remarkable sequence of rocks of which this coast is made date from the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous. These form the centre piece of the Jurassic Coast, a World Heritage Site designated in 2001. It’s a region as well explored by geologists as it is admired by visitors and has been long before the ‘Jurassic Coast’ was thought of.

In 1839 a geological fault just west of Lyme Regis caused a massive landslip. It caused an entire offshore reef to rear up out of the water ‘covered with sea weed, shell fish and other marine productions.’ The mechanics of this, known as ‘rotational movement’, were still then unknown.

The geologist and palaeontologist William Coneybeare lived nearby and his friend William Buckland happened to be staying. They were already engaged in the fierce debate about the role of single catastrophes in geological change, over against gradualist change, and reported to learned journals within days. It was not until the 1980s, though, that the event was fully understood.

The upending of an entire landscape created ravines, revealed new cliffs and left behind isolated rock pinnacles. After 1900 ‘the Undercliff’, as the site is known, was left un-grazed. The high canopy which towers over the visitor today is the result. It is essentially the West Country’s earliest rewilding project, all be it brought about by necessity rather than intentionally. It is an outstanding, easily accessible and closely studied example of how a landscape, freed from traditional use, can regenerate.

HPMAs would do the same thing but offshore and intentionally, which is more difficult because—except after major geological upheavals—the sea bed is out of sight to most of us. This surely explains much of the difficulty in establishing them. Governments have to be persuaded to steer the process. There’s a role for wildlife documentaries here, to generate national or even global waves of concern big enough that governments notice them.

But there’s a role for another approach, too. Peter Glanvill is a retired GP who has been diving Lyme Bay for more than 50 years. He was the first person I interviewed as lockdown measures were eased. I’d attended one of his slide-talks, given to a local association, just before the pandemic began.

Taught to dive in the Dart estuary by the same man who taught David Attenborough, Peter has been visiting the sea bed here long enough to observe the disintegration of war-time wrecks over time. The deck railings of a coal barge, torpedoed in 1918, have fallen off since he first saw it fifty years later. Today its boiler is covered in jewel anemones. An enthusiast for the Marine Protected Area, he has seen with his own eyes the recent return of angler fish and crawfish, the ever-greater numbers of octopus.

After spending time around Lyme Bay, the Victorian novelist Charles Kingsley recommended to his readers what he called the ‘wonders of the shore’: ‘for wonders there are around you at every step, stranger than ever opium-eater dreamed, and yet to be seen at no greater expense than a very little time and trouble.’

Many of the creatures Peter has photographed are ‘stranger than opium-eater ever dreamed’ and they are as near at hand now as they ever were. Kingsley also suggests that anyone wanting to know about the sea talk to fishermen and others who know it well. Descending in person to the sea-bed struck Kingsley as a strange idea but he acknowledged the antiquity of the human dream that we might one day visit the ocean floor.

The dream of flight was expressed long ago in the legend of Icarus. But the Greeks dreamt of diving, too, through the story of Glaucus. He was a fisherman who discovered a herb with which he could restore the fish he caught to life. Trying some of this herb himself he became immortal but also grew fins and scales, living thereafter in the sea and acquiring prophetic powers. Kingsley’s book, named after Glaucus, argues that the way we engage with the sea has always been primarily through the imagination.

Peter and I sit on separate benches in a park in Lyme Regis overlooking the bay. I ask about how he took to diving and there are several answers. One is ‘I just always want to know what’s around the corner.’ Another is the story of how his father, also a doctor, saw a film about Jacques Cousteau, learnt to dive and took his son along. Peter has preserved the logbook from his first dive, in search of spider crabs off Seatown in the summer of 1967.

It’s clear also, from the beauty of his photographs and from the way he talks about the creatures in them, that to observe closely, over time, is to care. Beach-cleaning groups have sprung up everywhere in recent years. Less well known are the divers picking old lead fishing weights from the sea bed and removing them by the tonne, or cutting old lobsters free from the carelessly discarded fishing line in which they become entangled. Peter has done both.

He is friendly with a generation of fishermen who took him out on their boats. He is an enthusiast for the Marine Protected Area not because he belongs to some online community which is in the habit of enthusing about it. He has seen for himself the growing abundance of fauna that depend on an undisturbed sea bed. He doesn’t speak about it with the puffery of an advocate but rather with a kind of modesty that Twitter gallops straight past.

What if the necessary reinvention of our relationship with the sea looks much more like this than it looks like Blue Planet 2? That relationship, after all, can only be reinvented in actual places. A screen may help with that—or it may hinder. Either way, it’s what happens in actual places which is decisive.

We’ve already seen that people have been paying attention to the underwater world here for much longer than 50 years. Kingsley’s Glaucus (1855) was part of a conversation, starting out as a review of Philip Henry Gosse’s A Naturalist’s Rambles on the Devonshire Coast (1853). Gosse had taken his family to live close to Lyme Bay, just outside Torquay, in a bid to restore his health. He restored it by engaging in what he loved best: ‘the study of the curious forms, and still more curious instincts, of animated beings… Few, very few,’ he went on, ‘are at all aware of the many strange… wondrous objects that are to be found by searching on those shores that every season are crowded by idle pleasure-seekers.’

Gosse would become the David Attenborough of his day, lecturing tirelessly on marine biology. The first underwater photographs were taken in this same decade, by an enterprising Weymouth solicitor called William Thompson. Gosse had also lived in Weymouth but seems not to have noticed this innovation. He had or, rather, had invented something that seemed to him a likelier means of mass persuasion, namely, the home aquarium. He invented a recipe for artificial sea water, too, so that specimens collected on Lyme Bay’s foreshore could be taken back to the living rooms of London or Birmingham and continue there to instruct and enchant.

Gosse was a distinguished biologist and a correspondent with Darwin. ‘Precision’, he wrote, ‘is the very soul of science’ and he meant it. But his ‘ramblings’ were not intended as a ‘book of systematic zoology.’ Their purpose was a wider one. He pressed into service ‘personal narrative, local anecdote, and traditionary legend.’ He quotes the poets and the Bible. His aim was to awaken as large an audience as possible to his news that ‘prodigies’ are ‘all in sight of inattentive man.’

To read Kingsley and Gosse on Lyme Bay now is to read two deeply engaged thinkers, both in touch with Darwin. Both men were Christians and even as they describe those prodigies, ‘all in sight’ to anyone with eyes to see, they enlist their surroundings in the ‘species question’, or debate about how (or whether) new forms of life emerge, how life reinvents itself.

It is for this too, surely, that they still merit attention. The great argument today does not pit biological science against literalist Christianity. But the clergyman-novelist Kingsley’s account of this is more prescient in some ways than the scientist Gosse. As they wrote, London’s Great Exhibition of 1851 was a recent memory and Crystal Palace was still a popular attraction.

It was also something close to a temple dedicated to humankind’s new and austerely ‘rationalised’ ideal, one which an energy-obese industrial civilisation would soon deliver. The vast cast-iron-and-plate-glass structure and its implied vision for the future appalled Feodor Dostoevsky when he visited London. It appalled Kingsley too. He repeatedly marvels at the intricate structure of even, or especially, the smallest marine creatures, contrasting the loveliness of a sea urchin’s design, say, with the grandomania and boastfulness of Crystal Palace.

Crystal Palace burnt down long ago but the world-view of which it was an expression is with us still. It is much the same philosophy that built our malls and motorways and cruise ships. The same philosophy has both overfished our oceans (to stock our supermarkets) and put endless obstacles in the way of real marine protection.

I mentioned earlier that a review on HPMAs appeared during lockdown and was largely ignored. One of those who wrote it, Joan Edwards, now with the Wildlife Trusts, was once involved with the response to an American oil company which had applied to drill through the reefs in Lyme Bay for the oil that is known to lie beneath them.

The oil company was dissuaded. Thirty years later those same reefs are part of a Marine Protected Area and Ms Edwards is on a panel making the case for fully protected areas to be established at last around our coast. The sediments that accumulate where the sea bed is undisturbed are known to absorb carbon more efficiently even than trees.

That review was engaging with the most urgent issue of our time. As we’ve seen, people have been thinking through this stretch of coast for a long time. So why shouldn’t we? Kingsley chuckled over visitors walking ‘up one parade and down another’, falling asleep over bad novels and having their umbrellas stolen, waking up for a nightlife which is ‘a soulless rechauffé of third-rate London frivolity.’ This is how ‘thousands spend the golden weeks of summer.’

Is what he describes entirely unrecognisable? And yet there the cup corals are, to this day, only a little way offshore. Between West Bay and Seaton, half a mile out, runs a submarine ledge teeming with marine life, rising to within 10 ft of the surface before it plunging to the sea bed. With Glaucus, then, with Gosse and Kingsley, with Glanvill and Edwards, let us glide along it in imagination and remind ourselves why knowing it is there has never mattered so urgently as it does now.

Cause and Effect

After a lifetime trying to make the world a better place, Chris Savory has written a book about his years as a peace activist. He talked to Fergus Byrne.

Taking part in the World Peace march across America in 1982, Chris Savory felt a sense of joy and a belief in the possibility that politicians just might sit up and take notice. He felt pride at being part of a principled movement for the betterment of humanity. But when the police arrived, he also discovered his innate fear of violence.

These are some of the memories that set the scene in Confessions of a Non-Violent Revolutionary, a book Chris has written about his time as a peace activist in the 1980s. The book tells the story from his first direct action—sitting on the floor of the Guardian’s office in London demanding to speak to a journalist, through to bravely standing between police and stone-throwing anarchists to prove non-violence was a better alternative. It follows the engrossing journey of one man’s total dedication to bringing about nuclear disarmament and details the many highs and lows of his years of political struggle.

However, the life that he led might have been very different. Arriving in Pittsburgh and joining up with the peace march in 1982 was just one aspect of a dramatic change in both lifestyle and ambition for Chris. In his A level year he had been tipped to be Head Boy, get a County trial for rugby and take Oxford entrance exams. But the Chris Savory that then went on to Oxford to study Economics was to disappear off the face of the earth. Like many people at that stage in their lives, something simply didn’t fit. As he points out in the book: ‘It’s not unusual for people in their late teens and early twenties to look at the future mapped out for them and recoil in horror at the restrictions and responsibilities that this implies.’ But for Chris it wasn’t just the restrictions or responsibilities that were an issue.

In 1981, living at his Gran’s house outside Cowley in Oxford he had become disillusioned with his perceived future. He asked college authorities to let him have a year off study to find his motivation again. Already a part-time activist for a year, he felt the threat of nuclear crisis was so acute he wanted to devote all his energies to averting it. He described himself as a performing ‘exam monkey’ and wondered ‘would my sixteen O-levels protect me from a nuclear attack?’ He was losing faith in the potential for a meaningful future.

As he cycled past Magdalen College he felt there were people of power and wealth who were oblivious to the threats posed by the escalating nuclear arms race and the prospect of ecological disaster. He knew from his time at Oxford that he didn’t have the right family background to ever rise to a position of power. His only hope, he thought, was to be a ‘trusty lieutenant’ to the ruling class. With the final exam of the first year over, he celebrated and on the way home bought fish and chips. He recalled, however that, ‘freedom tasted sour: salt, vinegar and loneliness.’

After dropping out of college he visited a careers advisor who berated him for throwing away his opportunity. Chris decided: ‘I’ll show you, you bastards. I will find a way to be authentic and change the bloody world into the bargain.’ He joined a commune in Wales where he was both influenced and irritated by the commune leader who accused him of playing at living an alternative life. ‘The last thing I wanted was to be a champagne socialist, a demo-dilettante, a smug middle class intellectual’ he said. Although stung by these criticisms, he knew his change of lifestyle and road to activism had emerged from a deep and genuine fear of nuclear holocaust.

His efforts over the next few years saw him organising and participating in a wide range of protest in Germany, Belgium, America and of course all over England. He was also part of a theatrical troupe that, through street theatre, brought a message of peace anywhere people would listen.

‘I was as shocked as anybody that I decided to do these things’ he said. ‘It was quite sudden in a way. Certainly up to the age of about 17 there was no hint of this possibility.’

In the end, however, his attempts to change the world, although valiant, were ultimately to be thwarted by a more powerful establishment. ‘The system, the state, the powers that be, fought back’ he said. And it’s not a spoiler to say that the end result has created a book that is as much about the death of opportunity as it is about the passion that drove many people to protest for so many years.

His journey, although starting from a deeply entrenched belief that non-violent direct action (NVDA) could make the world a better place, was ultimately futile. ‘Blockading bases hadn’t stopped Cruise and Trident. Mass demonstrations, peace marches, peace camps, die-ins, publicity stunts, petitions, opinion polls, letter writing, boycotts, voting, fasting, praying, singing, posters, conferences, nuclear-free councils and even our street theatre hadn’t got rid of a single weapon.’

Confessions of a Non-Violent Revolutionary came about for a number of different reasons. Speaking from his home in Bridport, Chris explained that the story of those years as an activist in ‘Thatcher’s Britain’ was something that he couldn’t really explain at a dinner party. He hoped the book would give an insight into the peace movement of the 80s as well as help him get a better understanding of how it had affected him, and perhaps some of those around him. He also hoped to pass on some of the lessons learnt. ‘One of the things about radical politics is that people don’t learn lessons from the past’ said Chris. ‘You dive into it full of youthful passion and often make the same mistakes that people have made in the past. If some young people read the book and learn a few lessons, then they might not have to go through some of the things I did.’

Confessions of a Non-Violent Revolutionary offers a depth of honesty that is refreshing, whilst also disconcerting. Protest, demonstration and challenge all play a vital part in the democratic process but there is little thanks for those that devote their lives to righting perceived wrongs. For Chris, and perhaps for many others, the battle becomes a mental challenge, not just in dealing with powerful authorities but also in dealing with disillusionment and self-esteem.

‘When I started down the road of protest and struggle for change, I had absolutely no idea how powerful this feeling of isolation from society would be, or how much pain it would cause me’ he said. ‘These feelings had pushed me towards a hatred of society which, coupled with despair at the failure of our movements and the still burning sense of urgency for disarmament, led me to a very dark place.’ He had a serious emotional breakdown and today suffers debilitating bouts of depression and exhaustion.

His hope now is that organisations will be more aware of the emotion that drives people to take a stand. ‘As a society we’ve got to take emotions more seriously’ he says.’ A lot of the violence and anger we see comes from emotional distress. It’s very easy as a young or even older person to decide to try to change the world. But when that hope is dented, it’s really important to deal with those emotions, and in the movements I was involved with, that didn’t happen.’

Chris has spent his whole adult life trying to make the world a better place through protest, local politics, working in the education sector, community campaigns and volunteering for social enterprises, and although it’s questionable whether that has been the best option for his health, he still believes there is hope.

Last year, for the first time in decades, he attended a protest. At the Extinction Rebellion demonstration on Waterloo Bridge he crossed the line to join the protesters. ‘I’m not ready to sit down for hours or to be removed by the police’ he said. ‘But I am able to identify myself as a rebel and show solidarity for an hour or two. It turns out that it’s not so easy to extinguish that flame of hope. As the crisis deepens I know which side I’m on.’

The Wild Silence

Life after The Salt Path. Jess Thompson talks to best selling author Raynor Winn

Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path has become a publishing phenomenon since it was released in early 2018. Her memoir of how she and husband, Moth became homeless—quickly followed by him being diagnosed with a debilitating neurological disease—was a Sunday Times top ten best-seller for more than 54 weeks, has been translated in 14 languages and optioned by a film company. Furthermore, people’s strength of feeling for her story has meant that at the 60 talks and literary festivals she’s attended (generally with Moth quietly sitting in the audience), tickets have sold out within days of going on sale.

So, to say there was a weight of expectation riding on her follow-up book, The Wild Silence might be putting it mildly.

“It was a completely different experience to write,” Raynor tells me, her voice soft and slightly hesitant when she calls me from her new home in Cornwall. We’d tried to Zoom but her phone was too old and cracked to have the capability—more of which later.

“The Salt Path had its own narrative arc, and I just needed to retrace it. I had Paddy Dillon’s guide to the South West coast path, with Moth’s pencilled notes in the margin, and everything else just followed.

“Last year, I started writing the sequel then suddenly thought, this is so shallow and it’s not saying what I want it to say. I decided that if I just did the obvious thing and wrote a follow-up then I wouldn’t be doing what I needed to do for myself. So I left it for ages, then came back to it with only four months before the deadline to hand it in. The whole thing, from start to finish… It was quite tricky.” She laughs. “But then I realised that I couldn’t think about who was going to read it. I had to put myself back into the framework; into the mindset I’d had when I wrote The Salt Path. Because it was only then that I could actually say what needed to be said—namely about the natural environment and our connection to it.”

The Wild Silence is indeed a very different book to its precursor. It’s a more fractured narrative, oscillating between childhood memories—many of which show how and why Raynor’s developed such a deep connection with the land—and recalling events which happened after finishing the walk. “I realised that I had to first go backwards, in order to explain what I was trying to say.”

Of course, few who’ve read The Salt Path can fail to have been moved by the love story of Raynor and Moth; and it’s equally heart-warming to read about how it all began when they met as teenagers, Moth’s hair “hanging in Celtic plaits, his old RAF coat flapping behind him.” He was already an activist, “magnetically drawn to the countryside, to the wilderness” and their first adventure involved a trip to Scotland, where their temporary campsite was washed away by a ferocious storm. What’s totally unexpected, however, is to read about the animosity her parents felt towards him, rejecting him, she writes, “with a venom and ferocity which wiped out every vision I had of what my family was.”

When I say this must have been a great sadness, she pauses. “They eventually came to terms with the fact that Moth was my choice, but I don’t think they were ever fully reconciled to the idea that I’d made the right one. Despite the fact that he remains the most extraordinary person I’ve ever met. So yes, it was one of the greatest sadnesses; because I’ve always wanted to keep everyone I’ve ever loved close in my bubble—as everyone does. I just had to have two bubbles.”

Writing with such honestly is a trademark of her style and one of the reasons that people write to her from all over the world, telling her their own stories: “some extraordinary, often personal, sometimes awful ones.

“To start with I was a little bit shocked, but then I began to realise that this was the beauty of what I’d done in writing The Salt Path—that it had connected people who felt they had no-one to connect with, creating a sense of a mutual humanity.”

Still, I ask, does she worry about having written about her parents’ feelings? “Even now I feel it’s a bit of dilemma. But at the same time it’s the truth of the way it was, so I don’t think it was something that would have come as a surprise to them.”

The poignancy of her reflections create a quiet sadness at the beginning of the book, encapsulated by the Cornish word ‘hireth’ which marks an early chapter. “There’s also hiraeth in Welsh, but there doesn’t seem to be an English term for it. It’s a longing for something that’s lost: for a home that’s no longer there; for something we never had; the fact that it’s never been in our lives. I think I was trying to express this sense of disconnection, of not feeling any attachment to my roots, my life—for everything had been stripped away from it.”

“Except Moth,” I say with relief—the state of his health having been my very first question. And indeed, the brilliant news is that his condition hasn’t markedly deteriorated in the last ten months. “He did have a downturn over winter, which wasn’t good, but we’ve tried to be a lot more active during spring and summer this year and his health’s picked up again.”

Part of the reason for this was the extraordinary opportunity of revitalising an overused farm, which Raynor and Moth were offered to rent by a man who’d read The Salt Path and loved it.

Set in 120 acres of a secluded valley that looks down to a creek, it includes 20 acres of orchard that’s now beginning to flourish as a result of the couple’s more sympathetic approach to land management. “It’s a brilliant use of the degree Moth did at the Eden Project after we finished the walk,” Raynor says, with obvious pride. “And in treating the land with respect, it’s extraordinary how quickly the biodiversity has exploded. But it also means that, finally, after the years that have passed, we’ve found our peaceful place.”

I ask her, somewhat nervously, whether the farmhouse is now habitable—for when they moved in it had been vandalised, with glue in the locks and a cacophony of mice living in the attic. “We’ve still got a few rodents,” she says cheerfully, “but at least it’s now got a bit of paint on the walls—and it’s dry!”

When we discuss the apples, with which they’re planning to make their first batches of cider this year, I suggest that they could market it as Salt Path Cider; and in so doing amass the fortune that not even her colossal book sales have created to date. “But it might taste awful,” she says. “Although I guess everyone might buy a trial bottle.”

Sadly, I suspect she’s not going to follow me up on my suggestion, just like her previous “Oh… okay” expressing her doubt about my idea that she should try and use her fame to wrangle a free phone to replace the eight-year-old, second-hand one her daughter kindly passed on. In fact she’s distinctly embarrassed by the idea. “Famous? Me? Really? Well, if I am, I don’t think it’s changed me in the slightest. I still get up, put the kettle on, let the dog out and think, okay, what am I going to do today? The only real thing that’s changed is that when the electric bill comes through the door it just makes me smile, because I know I can actually pay it.”

And of course the success of her book has, crucially, reunited her and Moth with the land—which is where she believes he thrives. In the last part of The Wild Silence they go on another walking trip, this time having Paddy guide them through Iceland. “It was a really tough trail, and yet it seems that the tougher the challenge, the better the effect on Moth,” she recalls. “After the first few days he was starting to feel strength and co-ordination return to his body; things that aren’t supposed to happen with his illness. We walked through miles of ash fields and dead lava flows—through an alien landscape that felt like a movie set in space; a land at its very beginning where the volcanic eruptions had just ended and the earth was starting to rejuvenate—just like Moth’s wellbeing.

“I do feel we’ve stumbled upon something,” she says. “Some doctors say it’s Moth’s own version of ‘something’; others point to the restricted diet or endurance training he experienced during our days on the path. Personally, I’m still looking for what the answer is; partly because CBD is still so under-researched.

“One of the things I’m particularly fascinated by is that most plants, to some degree or other, emit something called a secondary metabolite—it’s like a chemical that it puts out into the air, and is the thing that you see as a blue haze on a hot summer’s day when you look across a forest or woodland. Plants use it to protect themselves: from the heat, predators, pests or disease.

“There’s only been a small amount of research carried out, but it’s been found that the human body reacts positively to these chemicals, so it’s something I’m really interested in. For, just like the Japanese believe that the practice of forest bathing has the power to counter illness, I believe that Moth interacting with nature has tangible physical benefits.”

When I ask what their next trip will be, she gives very little away, but acknowledges that it will be within the British Isles and once again guided by Paddy. I wonder if they’ve finally met, and she’s delighted to say yes. “I was at an event in the Lake District and spotted him in the audience. I thought, I know that face, so we got him up on stage, and he was so lovely. Absolutely your genuine sincere man-of-the-hills sort of person that, from reading the guide book, we’d thought he’d be.”

When I ask what’s been the highlight of 2020 she guiltily proposes, “Lockdown?” before giving an alternate suggestion. We discuss that she’s not alone in thinking it. “Horrible as it has been for so many people, it couldn’t have come at a better time for me; giving me these quiet moments to reconnect with myself. And it’s meant that it’s been just me and Moth; which allows me to be my normal self—not really talking to anybody but him.”

What next for Business?

Learning about how local businesses have coped with the Coronavirus pandemic is the goal of a series of video interviews that Seth Dellow has conducted for The Marshwood Vale Magazine.

This month he interviewed Roger Snook of T Snook in Bridport and Simon Holmes from Axminster Books in Axminster. Both high street retailers, it has been interesting to hear how they have fared, and most importantly how they hope to deal with the future.

Simon Holmes took over Axminster Books about 18 months ago and just before the pandemic hit he was feeling that the market for books in print was picking up. Although the internet and digital reading had initially caused many independent bookshops to struggle and indeed many to close, Simon has seen an increase in trade over the last couple of years and had experienced a ‘pretty good year’ before he had to close in March.

With over 6,000 books in the shop his first thought was how to continue to trade. Inevitable that meant even more work than normal. ‘I was probably even busier’ says Simon, ‘trying to get different innovations up and running.’ He managed to get all of his 6,000+ books onto the website and traded through the lockdown.

Simon’s story may be echoed across many businesses in the area and his thoughts, shared in this video interview, are definitely worth hearing. His interview is available on our YouTube channnel at: https://youtu.be/a6qaBkrOV88.

Roger Snook’s business in Bridport started originally in 1896 as a gentlemen’s outfitter, although today it is best known as a hatter. The business now supplies hats all around the world. The shop also carries accessories such as bow ties, cravats, collar studs and even snuff. Roger says they also have ‘the largest selection of mustache wax in the empire.’

Roger’s experience of the pandemic was similar to most high street retailers in that he also had to shut his doors. However, he didn’t have the luxury of trading online. ‘With sizings and so forth on headware’ he says ‘you’ve got to try it on.’ He believes that buying a hat online is a waste of time because getting the right fit can only be achieved in the shop. Which means that expertise is a requisite when it comes to dealing with customers.

Thankfully, he is surrounded by staff that know what they are talking about. Praising their resilience and support during the last few months, in a time that no one could ever have prepared for, he called them the most brilliant staff you could possibly wish for. ‘They all should be given a degree in hatology’ he says.

Roger’s philosophy on dealing with the pandemic and the fall out for business is refreshingly blunt. There’s little we can do other than, ‘get on with it.’

Both of our business interviews offer fascinating insights into the effects of the last few months on our wider local community.

To watch them visit our YouTube Channel at: https://youtu.be/a6qaBkrOV88.

Happy Campers

My first camping experience was a damp and dismal one. I went on a school camping trip to northern France at the age of 14 and got thoroughly soaked. After we trouped around the D-Day beaches during the day in the rain, we all retired to our soggy little green tents and huddled together in a protective puddle as a torrential downpour reduced visibility to a few yards. Since then, whenever I read about the Normandy beaches, WW2 veterans or I watch The Longest Day movie on TV, I instinctively reach for my umbrella.

I underwent a second camping trial just a few years later when the whole family went to north Wales. I shared my father’s tent on a nearly perpendicular cliffside. When I say ‘tent’, I really mean a five-foot rectangular patch of old green canvas with lots of moth holes and a metre-wide rip along one side. It was my father’s old camping tent from the 1930s—an object of great nostalgia for him but not a thing of joyful anticipation for anyone else. It smelt of perished rubber, decomposed woodsmoke and damp under-cooked sausages with an over-riding odour of mould, paraffin and old socks. It was also missing about five tent pegs so we used steel barbeque skewers instead. The trouble with this is that they bend when you try to hammer them into solid mud which makes them incredibly uncomfortable when you end up lying on them at 2 am. However, my dad was very proud of his tent and took real pleasure from describing how his feet stuck out attractively at the end. He told me this was part of its clever design—healthy living with cold feet. He said it was a genuine antique and probably worth a lot of money at an old explorers’ auction, by which I think he meant an auction of ancient camping equipment rather than old men in duffel coats and snow masks. This was the real stuff—a tent from the golden age of camping when books like ‘With Scott in Antarctica’ or ‘Across Tibet by Yak and Husky’ were all the rage. If you went camping in those days, you were bound to be attacked by bears or tigers or wild Pathan tribesmen let alone minor discomforts like midges and tsetse flies. The 1930s were a time when boys had to prove themselves brave and sturdy enough to take on the wilds of nature and the elements. Camping was synonymous with survival and words like luxury and comfort had not yet been invented for life under canvas.

Anyway, I digress… Now back to sleeping on the side of a damp Welsh hill… My father kindly took the side facing downhill since his greater weight might act as a sort of book-end wedge to prevent both of us rolling down the precipice. This was fine with me, except my uphill side was the damaged side of the tent. The three-foot long hole ended just above my eyes so that when it rained (which it did most of the time of course), a river of water flowed down my hair and into my nose. We spent the longest three nights of my life on that hillside. I don’t think I slept more than five minutes during the whole time we were there.

As you can imagine, these two adventures made me swear never to go camping again. Others may extol the beauties of the wild outdoors, the fresh air and the joy of being at one with Nature, but I would rather take a ‘rain-check’—literally. How surprising it was therefore to see our garden full of tents last month. This did not include me of course, but my two sons and their families had decided that the only way we could spend a fortnight together on holiday was for them to camp out in our garden. Very clever really… the fear of Coronavirus and enforced self-isolation meant that nobody could actually sleep in our house, so we all ate our meals at opposite ends of the dining room table (luckily just over 2 metres long) before they retired for the night to their canvas home while my wife and I slept peacefully upstairs. This all worked surprisingly well—mainly due to the expert camping skill of my sons and the huge advance in tent technology. Yes, gone are the old days of ripped green canvas, the smell of damp underwear and leaky tarpaulins. Their new tent is now a model home with all mod cons. For a start, it is huge—it’s more of a small castle bungalow than a mere tent and everyone even has their own room (or ‘pod’) to sleep in! Such luxury! The whole thing is pristine and efficient and when it rains (which it always will when camping) you can keep dry and even stand up in its snuggly warmth inside. No more crouching under damp and rain-soaked fabric being scared to touch the sides or the water will come flooding in. This is the Buckingham Palace of tents.

My father would have hated it. “Too nice”, he would have scoffed. “Too namby-pamby, too dry, too comfortable! Might just as well sleep at home!” But I secretly rather wish we could have had one just like that on the side of a Welsh mountain…

John Ruskin did not Approve

I had not come across Tin Tabernacles until a member of “Bridport History Society”, John Lodder, now deceased, wrote an article referring to one in Bridport, known as “Christchurch, Walditch”. Walditch is an adjoining parish to Bridport. John Lodder was researching the history of Walditch and came across both St Mary’s Church and Christchurch. He found an entry in the “Bridport News” of January 9th 1880, headed “New Iron Church”, which stated that it was intended to erect an iron church in the parish of Walditch, near East Bridge, Bridport. The Rev W C Templer had complained in 1849 that the Parish Church of Walditch, St Mary’s, was too small for its congregation and was also in need of repair. The repairs were commenced and also plans for the iron church were made.

Rapid growth in population during the Victorian era led to overwhelming pressures to provide cheap, rapidly erectable church and chapel buildings. Enterprising companies designed church and other buildings in kit form, and produced catalogues, illustrated with drawings and prices. Size could be altered according to need.

The Devon and Somerset Advertiser for August 6th 1880 described the opening of the new church, Christchurch, on a site given by Mr W H Chick, and built in 10 weeks by a firm owned by Mr Broad, of Islington, London. The 1901 O.S. map shows it to be behind East Villas, opposite East Bridge in Bridport and west of the railway line, there then, i.e. near the River Asker, south of East Road. The church became known locally as “the Tin Tabernacle” and research by John Lodder shows that it became better attended than St Mary’s, in Walditch and he suggested that perhaps it drew some of its congregation from Bridport town. Christchurch had a small, neat bell turret over its entrance and music was provided by an harmonium. There were many varied preachers, in addition to Rev Templer. Mr and Mrs Rowe of Walditch were entrusted with care of the church. The opening service was attended by local dignitaries and clergy.

About 1910 the church was granted permission to build a Mission Hall, in the garden nearby at The Cedars, again in Walditch Parish. It was proposed that it should be constructed in the same manner as Christchurch, a wooden structure, covered with galvanised iron or “Elernit” sheets. The height of the building was to be 9 feet to the eaves and the foundations to be brickwork and sleepers. There were to be 7 windows, the tops opening and ventilation in the roof. All external doors would open outwards.

Christchurch and its Hall are thought to have been demolished between 1920 and 1933. The only picture of these buildings is a small photograph in the Bridport Museum collection which has been included in two books, “A Book of Bridport” by Short and Sales and “A Bridport Camera” by John Sales. The photograph is a view from Back Mills, the leat (filled in years ago, which was parallel to the River Asker) and Folly Mill. It may be that following the First World War, with great loss of life, the need for these additional buildings was diminished.

Some two years after this introduction to Tin Tabernacles our Programme Organiser, Roland Moss, arranged a visit to one still in use and not far away. This was St Saviour’s at Dottery, constructed of corrugated iron and wood lined, again with a small turret and a single bell. It is easy to miss, but is just short of the Bridport, Broadwindsor and Broadoak cross-roads. We were aided beforehand by a description from historian the Rev Bill Hill, who wrote that this church was conceived by the Rev Dr Alfred Edersheim, then vicar of Loders. Edersheim realised that his parishioners were quite scattered, in particular those living in Dottery and Pymore. He began holding services in local cottages, but by 1881 the congregation outgrew them, so his solution was the Tin Tabernacle at Dottery, which he was able to announce in the 1882 Loders Parish Magazine. The dedication ceremony took place in February 1882 to a full church, attended by nine clergy, headed by Archdeacon Sanctuary, Edersheim and his curate, W P Ingelow.

Furnishing inside St Saviour’s at Dottery, includes plain benches on either side and a small font. At the east end is the clergy stall and behind a pulpit, with the harmonium on the other side. Behind is a small vestry.

It appears that these “Tin Tabernacles” became the vogue in the mid 19th century, although they were not made of tin, but corrugated iron with a galvanised coating of zinc to prevent rust. The corrugations enabled sheets to be overlapped for a water proof joint. Internally they were lined with tongue and grooved boarding, perhaps of pine, which could be decorated as required by the congregation. Some were exhibited at the Great Exhibition in 1851, but John Ruskin, the Art Critic of the day, did not approve, as although practical they were not attractive architecture. “Tin Tabernacles” may not have met the architectural conventions of the time, but they met the needs and economic necessities of ordinary people.

Tabernacles were reasonably inexpensive, about £150 for a 50 seater or £500 for 350 seats. Conventional building materials, for the same size, would be considerably more expensive. The Tabernacles were surprisingly durable. Some 30 to 40 still exist in England, although not necessarily in use now. Some are listed buildings.

A local author, Michael Russell Wood, has published a book entitled “Dorset’s Legacy in Corrugated Iron”, which includes a variety of such buildings, as well as “Tin Tabernacles”. He lists two which are no longer in use for religious purposes, one is the Sherborne Baptist Chapel, once known as Coomb Church. The other was the Mission Hall at Highwood, near Wool, which is now converted and is in private ownership. The other buildings shown are on farms, aircraft runways and domestic.

I now realise that I passed another one every day of the first 15 or so years of my working life, in a small village called Sandy Lane, Wiltshire. It was well disguised for a rural situation by a thatched roof.

Look out for others on your travels.

Last November The Marshwood included an article entitled “More Grist for the Mill”. This did not extend East of Dorchester, for space reasons, so did not include the Sturminster Newton Mill, or “Stur” as it is locally known. This Spring I heard a short piece on BBC Radio 4 which told how it was being restored, with a view to re-opening for tourists, but when Covid19 appeared the work was “moth balled”. However they were approached by a possible customer for a small quantity of flour and then by a local baker, who was experiencing difficulties with supplies. I hope they have managed to continue. The mill is over 1,000 years old, so it predates the Domesday Book.

Cecil Amor, Hon President of Bridport History Society.

Not Everything is as it seems

Now you see it—now you don’t. From taxi driver to bank manager, Chris Howat has proved he can turn his hand to most things. He talked to Fergus Byrne about his magic life.

In a recent video, local magician Chris Howat held up a copy of the Marshwood Vale Magazine and pointed to an article about a dairy farm and its recent installation of a vending machine. He then proceeded to pour milk from that dairy into the magazine, magically making it disappear without falling through in a mess across his kitchen table. Pointing out that the milk was too good to throw away, Chris then poured it from the magazine back into a glass and drank it.

Was it magic? Was it an illusion? Was it sleight of hand or some kind of Photoshop trickery? Those were some of the questions that readers asked me afterwards. When I rang Chris to tell him everybody wanted to know how it was done, he simply said ‘Welcome to my world’.

One of the most common questions any magician hears is ‘How did you do that?’ and that very question is the reason they perform. Whether you are David Copperfield, earning millions at your trade, or Chris Howat who is relatively new to the art, it is that moment of surprise that every performer relishes. ‘When you perform a trick for someone and their jaw just drops to the ground and you could literally lift it up with your finger’ says Chris. ‘That’s the reaction I want to get—so stunned they can’t say anything. I’ve had that happen from ten-year-olds up to 80-year-olds.’

From the Shamen of old to the world of Harry Potter, or even simple card tricks on the kitchens table, that’s the joy of magic: no matter how old you are it takes you back to your childhood—to the days of wonder and amazement.

Chris has now been performing seriously for two years after his first gig at a charity event at Freshwater Holiday Park outside Bridport. On that occasion his performance required him to go from table to table, introduce himself and try to entertain people with magic tricks. He described at as ‘nerve wracking’ and ‘scary as hell’ but with a background in customer service and sales he had no problem with the level of confidence needed to try to engage with strangers. The real surprise, and pleasant bonus for him, was the level of enjoyment his audience experienced. He went home that night so giddy from the success of the event that his wife was convinced he was drunk. He was stone cold sober—but that was the evening that he got hooked.

Since then he has honed his skill and with increased confidence added more and more tricks. But magic isn’t just about planting confusion and wonder into the minds of the audience. It is as much about performance as it is about practising tricks. ‘I think that performance is the most important thing’ says Chris. ‘Yes it takes hours and hours of practise. Even the top magicians have to practise. And with that practise the tricks then come quite easily. But the performance, that’s where you need to know you are getting people interested and that’s how you progress. Because you’re trying to make an emotional connection with your audience, you’re trying to be remembered for an emotional moment of magic rather than some kind of egotistical performance of a trick.’

During lockdown, with all of his gigs cancelled he started doing a trick a day to put out on his social media platforms. Performing to a small camera was odd but at least he could see the trick is working.

However, not every show goes perfectly to plan. He talked about one occasion when he was performing at a care home in West Bay. ‘I had a new stage show effect I had trialled at a local open mic night in Weymouth and knew it was a fantastic effect which would entertain and wow people’ he said. ‘So the spectator chooses a fruit and I try to guess it and I can’t, I then pull out a tin of fruit cocktail and open the tin and pull out the fruit they thought of.’ Everything was going fine until he tugged at the ring pull on the can and it broke. ‘Luckily they had a can opener so I opened the can and for some reason I decided to only open it three quarters of the way, and then bend the lid with my finger’ he said. ‘As I bent the lid I cut my finger quite deeply. The fruit and the tin got covered in blood and I had to go wash my hand and use three plasters to stop the bleeding.’ This not only made a mess of the trick, the fruit and the show, but as a result he couldn’t bend his finger, thus restricting his ability to shuffle cards, move elastic bands or do most of the tricks he would normally do. In retrospect it is probably quite funny, but at the time he tried a few different tricks and ideas with limited success and ended up leaving to go back another day to finish the performance.

When we spoke, Chris had been furloughed from his day job since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, which means he has also been unable to enjoy the regular gigs that he has been building up since he first got the passion for magic. This year he had built up a healthy schedule that included birthday parties, weddings, special celebrations and of course summer fetes.

However Chris has used the time to progress. ‘COVID has been a blessing and a curse’ he says. ‘While I’ve been furloughed it’s given me time to work on new magic and I’ve had time to script and complete a whole 90-minute stage show. That’s with effects and staging as well.’ He is now in the process of re-scripting that to make sure it has all the key emotions and elements he needs for the whole performance. ‘So the plan is that next year, when we can, I can run two or three test shows and then get the show out, which will obviously bring in more work.’

One of the things that Chris often deals with is people doing a double-take when they see him—and that’s not just because of his magic. Although they might recognise him from Instagram and Facebook, his face will be familiar to many locally. He and his father ran a taxi firm in Bridport for many years before he left to work in Lloyds TSB where he became deputy manager of the Bridport branch and then manager of the Dorchester branch. With that background, it’s inevitable that people will wonder if he can magic up some cash. Because let’s face it, any of us can make it disappear.

To learn more about his work or get in touch visit Chris’s website at https://chmagic.co.uk.

New Life for Rural Media Charity

Archive film shows in our village halls and bigger venues have been a real draw for local audiences over the years. Margery Hookings reports on the latest news from the rural media charity Windrose, which has just been awarded grant funding to continue its innovative work.

Grant funding has enabled rural media charity Windrose, known for its film archive of Dorset, Somerset and Wiltshire life, to forge ahead with new community-based work.

All its current projects had been cancelled or postponed because of the Covid19 pandemic.

‘It left very little to cover overheads or keep the team together,’ director Trevor Bailey said.

‘Then the National Lottery did a wonderful thing. It paused all of its normal grant giving and went over to supporting charities through the worst of the crisis. This was short term funding but, so long as the position does not become hopeless again, it has prevented many disasters.

‘In Windrose’s case, we applied for funding to help with continuing overheads for four months but we did not want money just to prop things up. We also asked for support that would help us to continue to do useful work and to develop projects for the future.’

The National Lottery Heritage Fund has helped Windrose with a grant of £30,000 to fund a range of work, including ensuring the film archive continues to be looked after and used and also allowing the team to work on the creation of future projects.

Mr Bailey said: ‘That’s just what we want. We don’t want to be kicking our heels and we certainly don’t want to lose the skills and knowledge that are vital to Windrose. We want to be active and doing some good in the present situation.’

One new project that will be doing just that is a partnership with Age UK North, West & South Dorset funded by a £5,000 grant from Dorset Community Foundation.

‘We will be contacting and interviewing older people isolated at home, by telephone or Zoom, to record their memories and life stories,’ Mr Bailey said. ‘The recordings will then be shared with other older people and, via websites, with the wider public.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund has also funded an initiative to publicise Windrose, its work and the resources it has available much more effectively than before.

‘This is something which we have never been able to do before. It has always been one of our greatest inadequacies. Now we have on board a professional in PR who knows our work.’ Mr Bailey said.

And Arts Council funding of £14,016 is supporting a project combining old films and live singing for groups, assisted by Alzheimer’s Support Wiltshire.

‘It works beautifully to involve people and stimulate memories,’ Mr Bailey said. ‘The difference is that we are now going to deliver it online by involving carers using Zoom.’

‘All this is happening over only the next few months but it is really encouraging to know that we have the means to pursue new ideas, involve new people and reach out to the community as never before.’

Windrose was set up in 1984 under its earlier name of Trilith. It uses the visual and audio media for educational, archival and creative work in rural communities throughout Dorset, Somerset and Wiltshire.

Over the years, it has presented 256 archive film shows in village halls, cinemas, theatres and arts centres. Windrose has also created a huge range of media projects for local communities, including radio training for young people, its far-reaching internet radio station for farmers, video and CD productions along with opportunities for new musicians, poets and playwrights and projects for people affected by Alzheimer’s and isolation.

Said Mr Bailey: ‘We have survived and developed for nearly 36 years without a penny of regular funding. We have simply gone on creating project after project and fundraising for them one by one.

‘Many people tell me that a charity cannot keep going that way but we have. We have never had subsidies just to exist. All of our funding has been for practical work. The great thing is that we have been able to hold our core team of media and community work experts together for all that time.’

About Windrose

Windrose was set up in 1984 under an earlier name, Trilith. It is a registered charity (no. 1136144). Its purpose is to use the media to undertake educational, archival and creative work in rural communities.

In 36 years Windrose has never had any regular funding but has developed a long succession of projects which respond to community needs, fundraising for them one by one

All of Windrose’s work is based on outreach into dispersed communities and upon the close involvement of local people from a very wide range of ages and backgrounds.

The Windrose website is currently being revamped. In the meantime, visit the Close Encounters website http://closeencounters-mediatrail.org.uk/ to find film and audio from Dorset, Somerset and Wiltshire.

Creative innovation

My first contact with Windrose was in its previous guise of Trilith at a film show at Broadwindsor’s Comrades Hall.

I was captivated by the old film footage from the area. It was an incredible experience watching people from an age gone by, going about their daily business in a rural setting I knew so well.

And when the show was over, Trevor Bailey announced that Trilith was starting a new project called Farm Radio. Volunteers—women in particular—from farming backgrounds were being sought to train as reporters for the internet radio station.

I’m a farmer’s daughter and granddaughter but I thought my connections to agriculture might be a bit tenuous. And as a print journalist, I wasn’t sure I was what they were looking for.

But, in any case, I stepped forward and joined a growing team that went out and about, talking to the agricultural community and recording their fascinating stories and events.

Sadly, Farm Radio no longer exists, but it was a fabulous experience and led to me doing more work for Trilith, including recording audio trails and researching.

Windrose’s work is a wonderfully creative, eclectic mix, using oral history, music, the spoken word and, of course, its marvellous film archive, to produce something very special.

This latest funding enables the charity to continue with its community-based projects in its own innovative way.