Just weeks after the publication of a new book about the British intelligence services, the new Director-General of MI5 has promised more ‘visibility’ from his organisation.

Speaking at his first media briefing since taking the top spot at MI5, Ken McCallum detailed the threats facing Britain, including State interference by Russia. He also suggested that although his organisation needed to be ‘invisible’ in much of what it does, he wanted parts of MI5 to be more visible and open to the public.

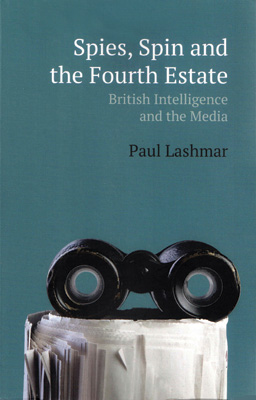

However, after a lifetime of studying the intelligence services, Dr Paul Lashmar, author of the recently published, Spies, Spin and the Fourth Estate, takes these comments with a large amount of scepticism. Pointing, for example, to McCallum’s comments about Russia being a threat to British democracy Paul says: ‘For those of us that have been calling for an inquiry into the impact of online disinformation by Russia and other hostile forces on the 2016 Brexit vote, we are told by MI5 and government “move along here, there is nothing to see”—they can’t have it both ways.’

Head of the Department of Journalism at City University and an investigative journalist for over forty years, Dorchester based Paul makes the point in Spies, Spin and The Fourth Estate that there is much to be concerned about for British democracy from within the security services themselves. Increasingly invasive powers, a lack of accountability and oversight, and ‘massive’ reliance on private contractors are some of the points that he believes need to be addressed to make sure the intelligence services are not only robust enough to do their jobs, but also to protect the freedom of the people they are there to safeguard.

In his book, Paul traces the activities of various organisations tasked with protecting the country through The Great War, the inter-war years, the Second World War and the Cold War, right up to the present day and the ‘War on Terror’.

His detailed account, drawing on years of research and experience writing about the security services, and especially their reliance on and interaction with journalists, paints a fascinating picture of a powerful force. One that, in general, he believes is a force for good. But he is concerned that it may have already amassed data way beyond its needs. Speaking about GCHQ, for example, Paul explains: ‘I don’t think people understand how powerful GCHQ working with the Americans now is. It’s not about what they might get about you in the future. They already have in their files a huge amount of detail about everybody in the country—it’s sitting in computers. It’s frightening. They build huge warehouses full of servers where they download metadata, phone calls etc. With an increasingly authoritarian air to the current government, that’s frightening, really frightening.’

Despite new regulations attempting to monitor and regulate intelligence services, Paul’s depth of frustration with their intrusive activity is mirrored by his concerns about whether we have the ability to monitor these organisations the way we should. ‘If you are critical of the intelligence services you are perceived to be anti-intelligence’ he says. ‘I am not at all anti-intelligence. But I believe they should be properly accountable. And they are not properly accountable, even with the new regulations. The fact that the Government tried to put Chris Grayling in as the chair of the Intelligence Security Committee (ISC) demonstrates the appallingly poor accountability that currently exists and there’s lots of evidence in the book that supports that.’

In their defence, Paul is quick to point out some ‘extraordinary good work’ done by Dominic Grieve as Chair of the ISC. But he also says that ‘by and large since 1996 the ISC has been a cheerleader for intelligence, rather than a critical independent oversight mechanism. We haven’t had effective oversight for just about all that time really, except for a short period around 2016 to 18.’ Paul questions whether we have the manpower and resources to monitor such secretive organisations properly. ‘We don’t have the skill base in accountability to deal with it’ says Paul. ‘They just don’t have enough inspectors and people who understand what is going on at GCHQ to do that. It’s a really interesting question. This isn’t me saying that GCHQ and other amazing agencies aren’t doing great work in monitoring terrorists and protecting us, but it’s the most powerful secret tool in the country by a long shot—and it needs to be regulated properly with oversight. The history of intelligence, as laid out in my book, shows that if you give people who are operating in secret, ‘power’, they will always push the edges of the envelope—push it that bit further—interfere with this or that bit of politics—push the people that their politics supports—embarrass people…’

From undermining ‘isolationists’ opposed to America entering the Second World War to intensive propaganda efforts in Northern Ireland, as well as the promotion of moderate Islam, Spies, Spin and the Fourth Estate offers no shortage of detail about security services tactics and ‘tradecraft’ over many years. The word ‘Spin’ in the title alludes to the many occasions where journalists and writers were co-opted to perform as propagandists. Despite the fact that a journalist’s role should be, as Paul puts it, to act as a ‘challenge to the presuppositions that exist in the intelligence world as elsewhere’, from Daniel Dafoe to Roald Dahl, many journalists’ talents have been used to assist when necessary. In fact, there were those that made their careers by being a pair of ‘safe hands’ and therefore were granted early access to information—as long as they spun it with the required angle. In the main, these were more establishment oriented than left-wing. They tended to be ‘people from the right or centre-right, certainly not from the left’ said Paul. ‘Those journalists, academics and politicians appeared to have a level of knowledge that other people from the left didn’t have and therefore their careers blossomed. It was a very effective mechanism for isolating people from the left because they couldn’t get that information.’

Making the point that intelligence gathering and investigative journalism utilises similar techniques Paul reminds us that ‘the fourth estate’ or journalism, has another aspiration: ‘the concept of the freedom of the press within a democracy suggests that the news media preserve the citizen’s liberties from an overbearing state and corporate sector.’ However, he says that ‘reporting critically on the world of intelligence is regarded as one of the most difficult specialist beats in journalism as it is, by definition, a world of secrets.’ Today, the ability to simply report, let alone investigate, has become more than difficult. Not least due to the suborning of journalists over many years. Today the game has changed says Paul. ‘When I started out, if you were sent to a trouble spot as a journalist, you could rush around and wave your press card and people would think “oh, that’s a journalist” and not touch you. These days, the assumption is that you are a spy, or you’re up to no good, or you’re just a lackey of the bourgeois media. We both know journalists who are now much more cautious about going to danger spots because they might get kidnapped or taken hostage. Or even worse beheaded and killed.’

Spies, Spin and the Fourth Estate shines a light onto activities that may have been undertaken with the intention of protecting western democracies but the long term result is an abuse of power that makes it increasingly difficult to hold to account. ‘Intelligence agencies will tell you they are there to defend democracy, so why is it they have had a hundred years of subverting journalism and the media?’ asks Paul. ‘It seems to me, the notion of the freedom of the press is a fundamental aspect of democracy. And no one ever asks that question. Why do intelligence agencies consistently misuse the media for their own benefit? Given that they are interfering with the freedom of the press and the free flow of information. They have always interfered with it. I think that’s a big question that’s never been properly answered.’

Secret Empire

Ancient Fortresses

Uncovering the rich history of some of the Marshwood Vale’s iconic hillforts – by Connie Doxat

Standing in the belly of the Marshwood Vale, several distinct lumps protrude over the horizon. Of all these impressively elevated spots, one of them has a remarkably flat top—the Table Mountain of West-Dorset perhaps? Another, sitting at the roof of the vale wears a dark green cloak of beech and oak trees. A third, is a vast plateau which towers over its conjoined but miniature twin less than a mile South. All these spectacular sites are of course the unmistakable hillforts of Pilsdon Pen, Lewesdon Hill, Lambert’s Castle and Coney’s Castle, respectively–arguably some the most distinctive items on the area’s skyline. However, alongside such splendid natural scenery, the rich and ancient history of these hills is in many ways just as thrilling to discover…

Anyone familiar with the marvellous walking in the Marshwood Vale will have summited Pilsdon Pen, perhaps the best preserved out of this unusual cluster of hillforts. This distinctively angular spur gains its name from the ancient Pilsdon community, from which Pilsdon Pen’s vertical sides majestically rise (the ‘Pen’ derives from the Welsh word for head or top). Once you’ve scrambled up its ramparts to the top – reached quickly from a short but steep walk from the National Trust car park—it soon becomes easy to understand why this location may have been the longest inhabited spot of all the four hills. Pilsdon’s outstanding 360-degree views are unrivalled by those of its neighbours, providing a panorama not only rare for the surrounding region, but the country as a whole. The archaeological significance of Pilsdon Pen, however, wasn’t truly discovered until after the 1960s, when its former owner Michael Pinney gave permission for Peter Gelling of the University of Birmingham and his wife, Margaret, to begin excavations on the site. Their findings revealed the remains of 14 Iron Age roundhouses, and thus provided evidence that a considerable population once inhabited its exposed top. Further surveys conducted by the National Trust in 1982 and Historical Monuments of England in 1995 uncovered flint tools and burial mounds thought to date back as far as the Bronze Age, suggesting the site has seen human activity for some 10,000 years.

The impressive height of Pilsdon (277m) is only slightly trumped by its closest neighbour, Lewesdon Hill, which stands triumphantly at 279m, higher than both Lambert’s (258m) and Coney’s (210m) also. This miniscule but rather meaningful 2m difference between Pilsdon and Lewesdon wasn’t actually recognised until recent surveys, granting it the crown as the county top of Dorset and placing it as one of its only four classified ‘Marilyn’ peaks. As well as the topography, the actual design of each fort is also fascinating—particularly that of Lambert’s and Coney’s Castles, which were actually built as together a pair. The reason for this unusual structure is thought to lie in the control it gave the occupants of Lambert’s (which was the far larger settlement) over an important track which ran a mile to its South (beside Coney’s). Moreover, whilst Lewesdon, Lambert’s and Coney’s Castle display a univallate design, consisting of only one large defensive bank, Pilsdon Pen’s is rarer, with a complex network of ditches and ramparts known as a multivallate fort.

Although different in design, the purpose of all four hillforts remained relatively similar; acting as strategic and easily defendable settlements in which people of the Durotriges tribe concurrently lived. The Durotriges were one of many tribal groups to exist during the Iron Age, and occupied large swathes of Wiltshire, Dorset, Devon and Somerset. Bar the system of hillforts visible today, most elements of Durotrigan society have been destroyed over time, following years of destruction by Roman invasion and natural slippage in the region’s geology and thus many questions about the culture have been left unanswered. However, a remarkable collection of silver coins is one of the only artefacts to have survived the millennia and is even thought to be one of the only systems of coinage to exist in Britain prior to the Roman conquest (AD 43). The sheer rarity and volume of such coins found across the region help to illustrate the superior wealth and craftsmanship of the Durotrigans in comparison to neighbouring groups, such as the Dumnonii to their West. Despite their affluency, the population of the Marshwood Vale remained sparse in this period, and it is hence only natural to wonder why the Durotrigan’s established these four settlements within such close proximity to each other; surely this strained resources like firewood, or impeded the defence of such a vast territory? However, it is thought that the grouping of these forts did indeed serve a strategic purpose, providing a central meeting point for the dispersed Durotrigan population, which is considered to have been more of a tribal confederation than an organised municipality.

The history of these forts also extends far beyond the Iron Age and they have played an important part in shaping the identity of the Marshwood Vale ever since. For anyone with an interest in literature, the possible impact of these hills on the poet William Wordsworth is fascinating. Between the years 1795 and 1797, Wordsworth and his sister, Dorothy, lived at Racedown House in Birdsmoorgate and the couple quickly developed a fondness for the surrounding peaks (the house being located close to the centre of all four forts) . Although William never explicitly mentioned any of these historic sites in his work, their similarity to the rugged crags and open skies synonymous to his writing suggests their influence in his pieces written during his time at Racedown. A diary entry written by Dorothy during this period, illustrates this “we have hills which, seen from a distance almost take the character of mountains, some cultivated nearly to their summits, others in their wild state covered with furze and broom”, alluding to the distinctive shape and yellow gorse which characterises their flanks still today.

Lewesdon Hill also has a place in political history as one of the many hilltop beacons used to alert Sir Francis Drake and his men of the impending Spanish Armada fleet in 1588, initially spotted off the Cornish coast. British maritime history has also involved Pilsdon and Lewesdon due to their use as navigation aids, known as the ‘Calf and Cow’, which helped to guide sailors across Lyme Bay for centuries. What’s more, the presence of pillow mounds at Pilsdon suggest that the area saw the practice of rabbit rearing, popular during the medieval period after the Black Death saw incomes tumble with plummeting grain production. Coney’s Castle is also likely to have seen medieval rabbit warrens, with the word ‘Coney’ translating from the Old English for rabbit. In the last century, Lambert’s Castle’s was also used as the site for an impressive county fair, which took place annually between 1709 and 1954. A grant from Queen Anne originally allowed the fair to be organised, and saw market stalls, animal enclosures and a large racetrack all built where dogwalkers stroll today—with such a glorious view it must have been quite the spectacle!

The fact that the history of this tight cluster of hillforts spans millennia is truly a testament to the sheer depth and variety of their past, and we should celebrate how these four hills have shaped the local culture and beautiful landscapes of the Marshwood Vale we enjoy today.

Gulliver’s Travails

Some time ago I gave a brief mention of Isaac Gulliver, a renowned Dorset smuggler, but I think he is worth more than just a brief note. He was one of the best known of local smugglers, trading in wine, spirits and tea, but he changed his lifestyle later on to become an upright citizen.

Isaac Gulliver was known as the “Gentle Smuggler”, presumably to distinguish him from the others who were anything but gentle! He was born in Wiltshire in 1745 and moved to Dorset and married Elizabeth Beale at Sixpenny Handley in 1768.

Gulliver frequently operated from Lyme Regis and is said to have employed 40 to 50 men who wore a kind of livery, with smocks and powdered hair, so were called the “White Wigs”. At Lyme they had a room open to the sea at the mouth of the river, where they could rest, eat and drink, whilst waiting for their call to business, only 100 yards from the Customs House. In 1763 Gulliver brought contraband totalling £20,000 into Lyme and other ports. In 1776 he landed goods in full view of the Customs men. From about 1789 no goods could be seized above the high water mark, so wine was landed close to the Customs House and allowed to remain on the beach close to the Customs House and the Cobb-gate.

Gulliver used vessels of about 100 tons, called “tonnagers”, with papers made out from Cherbourg to Ostend. One boat was boarded off the Cobb and found to be loaded with wine, but the next day she entered the Cobb without a single drop of wine on board. Mr Raymond of the Customs house seized her and the smugglers were tried at Dorchester, but pleaded that they had thrown their cargo overboard to avoid the vessel sinking. The smugglers were safe, with all the hundreds of bottles of wine stored at Bridport.

A bribed Customs Officer said they had a conversation, saying “Let us be off, or we shall share the same fate as Admiral Kempenfelt”. (Admiral Richard Kempenfelt, 1718 to 1782, died when HMS Royal George, a 100 gun warship, accidentally sank off Spithead and Portsmouth. He and 800 others were drowned.)

Isaac Gulliver was a friend of the Rev William Chafin, Rector of Lydlynch, owner of Chettle House and a wine connoisseur. Chafin was said to have fathered three illegitimate children. Chafin sold Gulliver Eggardon Hill, where he planted trees within an octagonal bank and ditch, to act as a landmark for his smuggling ships. The trees were said to have been felled later on a government order. It is said that Gulliver also owned Kings Farm (House) or North Eggardon House. Of course, the “Spyway Inn” is close to Eggardon. His route to Bath and Bristol with his contraband was supposed to be either from Bridport Harbour, Burton Bradstock or Swyre, through to Puncknowle, Powerstock, over Toller Down, Corscombe and Halstock. Shipton Gorge boasts a “Gullivers Lane”, but this may possibly refer to another Gulliver.

Isaac Gulliver owned a lugger “The Dolphin” and a well known white horse. He used a shop to sell wine and spirits and some say he once evaded capture by posing as a corpse and on another occasion dressed as a shepherd.

In 1779 the Salisbury Journal advertised the sale by auction of 24 of his pack horses and in 1782 he took advantage of the Government’s pardon for smugglers who entered the navy, or could provide two substitute men. Gulliver could easily afford to bribe substitutes and then gave up smuggling tea and spirits, but continued wine smuggling which was apparently less serious. There is a story that he was pardoned for providing information about a French plot to kill King George III.

Gulliver became wealthy, owning a luxury schooner and had two daughters who married well, Elizabeth married into a banking family and Ann a Blandford doctor. Isaac became an upright citizen and a church warden. He died in 1822 and is buried in a vault in Wimborne Minster.

An Act of Parliament of the time made the lighting of fires along the coast, as a signal to homeward- bound smuggling craft, a punishable offence.

William Crowe, Rector of Stoke Abbott from 1782 to 1788, wrote a poem, “Lewes-Dun Hill” which refers to Burton Bradstock:

“These, Burton, and thy lofty cliff, where oft, The nightly blaze is kindled; further seen…The stealth – approaching vessel, homeward bound – From Havre or the Norman Isles, with freight of wines and hotter drinks, the trash of France, – Forbidden merchandise”.

Thomas Hardy, in his novel The Distracted Preacher tells how Lizzy Newberry lit a bush on the cliff, at new moon, to warn smugglers that the “Preventive-men” were about locally. She expected they would then sink the tubs, strung to a stray-line at sea, to be later raised by a “creeper”, a grapnel. In the same story Hardy tells how the tub carriers carried “a pair of tubs, one on his back and one on his chest, ….slung together by cords ….weighty enough to give their bearer the sensation of having chest and backbone in contact after a walk of four or five miles”. He also said that almost everyone in the villages was involved in the gangs, even the clergy benefitted from the trade and churches were good hiding places for smuggled goods.

Rudyard Kipling wrote Traders of the Night, a poem, which includes : “Five and twenty ponies trotting through the dark, Brandy for the Parson, ‘baccy for the clark”.

Kipling went on to say that if you were outside as the “Gentlemen” came by, you should turn your face to the wall and not look at them, or let them see your face. Presumably then you would not recognise them, or they you.

Eventually the Government reduced the duty payable on many of the goods liable to be smuggled, which reduced the profit for the smuggler and the trade ceased. Or has it? Have you heard strange noises in the countryside on a dark night recently?

Bridport History Society is meeting on Zoom during lockdown. The November meeting is on Tuesday 10th at 1.30 for 2pm and is “The Bindon 1838 Landslip” by Richard Edmonds. For details of the Zoom, please contact Jane Ferentzi-Sheppard on 01308-425710, or email jferentzi@aol.com.

Cecil Amor, Hon President of Bridport History Society.

A Sense of Place

Twenty years ago, seventy photographs were chosen by Ron Frampton and Joy White to be part of an exhibition of monochrome images to be exhibited at The Town Mill in Lyme Regis. It was the first year of the new Millennium and the exhibition, along with a catalogue comprising nearly a third of the photographs, was a celebration of the art and beauty of black and white photography. Most of the photographers who participated had studied with the late Ron Frampton at The Somerset College of Arts and Technology and at Dillington House in Somerset.

The exhibition, A Sense of Place, demonstrated the power and beauty of the monochrome image in subjects ranging from portraiture, coastal landscape, architecture, documentary and art photography. As well as the talent of those who took the photographs, it also demonstrated the excellence of the tutor, Ron Frampton, whose passion for both photography and the West Country became legend. This month we have been in touch with some of the photographers whose work appeared in the catalogue to find out what they are doing now, and how much the experience of learning Ron’s techniques of photographing and printing stayed with them.

Nicky Saunter remembers the joy of ‘seeing each image come to fruition in the darkroom, hanging the work together, the excitement of publication, and being pushed to Ron’s exacting standards of professionalism.’ A ‘serial entrepreneur’ who set up and developed the Boston Tea Party coffee house chain, Nicky now works in advocacy, acoustics, drug policy, land-based training and nature restoration, and having cofounded the Beaver Trust helps communities to welcome beavers back to Britain. Nicky says she still uses every technique Ron taught her. ‘His inspiration was to teach us by osmosis’ she says. ‘We worked together, looking at the masters, appreciating each others’ successes and just loving monochrome photography. Along the way the technical knowledge simply seeped in.’ She has even reestablished her darkroom explaining: ‘There is nothing quite like the quiet magic of silver reacting on paper to create a unique image every time and the physical beauty of a handmade photograph. I sometimes miss the camaraderie of my darkroom mates though.’

Justin Orwin, whose image of the Pilgrim was chosen for the cover of the Marshwood Vale Magazine in 2002, went on to make a career out of photography. Initially he worked on weddings and portraits and now runs a commercial photography studio in Ilminster, working with local manufacturers and Interiors specialists. ‘I also spend a lot of time photographing both people and landscapes as part of my more personal work, using the skills Ron taught me about composition, exposure and printing in the darkroom’, he said. ‘I am also teaching others the intricacies of traditional fine art monochrome photography with my workshops.’

‘A Sense of Place was, for me, a milestone in my photography. I had never had a photograph in print before and I had excitedly pursued subjects suitable for the book. This gave me great confidence in my photography and in photographing people. You always knew with Ron that if it wasn’t good enough it wouldn’t be going in the book or the exhibition, so you really had to work hard to reach his exacting standards.’

Bill Wisden Hon FRPS, Chair of the Distinctions Advisory Board at The Royal Photographic Society, wrote the forward to the catalogue. He pointed out that the ‘removal of the reality of colour’ enabled the photographer to express ideas in a much more subjective manner.

Pauline Rook, another successful photographer who contributed to the exhibition had initially been inspired by the photographs of James Ravilious. She did a day of portrait photography at Dillington House with Ron Frampton and said: ‘that was the day my life changed.’ She spent five years under what she described as his ‘patient guidance’ and went on to become a successful commercial photographer. She also took on many ‘wonderful commissions’ including documenting a year in the life of Cannington College and a project with James Crowden to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the signing of Bridgwater’s Town Charter. ‘I have had a wonderful journey over the past 20 odd years’ said Pauline. ‘It has opened so many doors for me and I have met so many interesting people and seen some wonderful sights. I am truly grateful to Ron for unlocking all this for me. I continue to photograph as keenly as ever and have taken part every other year in SAW (Somerset Art Weeks).’

After assisting fellow student Pauline Rook for a year, Katia Marsh set up her own business and has been working ever since. She considers herself extremely lucky to have been in the right place at the right time and gained such a solid and meticulous grounding in the art and practice of photography. As a single mum bringing up two small children in rural Dorset, Katia remembers it as ‘a total dream being able to study what I loved, part time in the evenings and gain a highly respected professional qualification at the end of it!’ She now specializes in social and commercial photography—weddings, portraits, events, and works with businesses and charities. ‘Whilst a career in photography hasn’t made me a millionaire, it’s providing me with fabulous opportunities’ she said. Including ‘documenting the origins of Bark Cloth in remote tribes of Papua New Guinea, Prince Philip’s charity work in various royal palaces, Blue Lias and amonites in Mustang Nepal, Margaret Atwood with the penguins at London Zoo.’

Kirsten Cooke remembers that Ron was very strict in his darkroom technique. ‘Ron instilled an incredible way of working in all of us,’ she said ‘Everything had to be clean, everything had to be precise.’ Discipline is something that is echoed by most of those that worked with him. ‘We made meticulous notes with every image that we put through the enlarger. So you got into this habit. If you go back in a year, or two year’s time, you have your notes. That kind of thing stayed with all of us I think.’ Kirtsen carried on as a photographer for many years and now has a special passion for photographing empty houses and buildings. ‘That’s something that I’m fascinated by, because I think there’s a residue from whoever lived in the house before it’s sold or how houses move on from one family to the next.’

Over the many years since Ron Frampton began contributing to this magazine, we have been very fortunate to have been able to publish and publicise photographers that have worked with him. Especially Robin Mills and Julia Mear who still work on our cover stories.

A Sense of Place, the exhibition and the catalogue are a fascinating reminder of, and representation of, an art that captures more than the eye can see.

For more information visit:

Katia Marsh: www.katiamarshphotography.co.uk

Pauline Rook: www.rookphoto.co.uk

Justin Orwin: www.orwinstudio.com

Kirsten Cooke: www.kirsteningercookephotography.co.uk

Nicky Saunter: www.beavertrust.org

Life after Lockdown November 2020

Your stories from around the World

With the UK facing more lockdown measures, Margery Hookings, in the third article in a series about people and the pandemic, speaks to relatives and friends from around the world to find out how Coronavirus is affecting their lives.

Mother-of-three Marie Besson is back in her native Canada after living in America’s deep South for the last five years.

It was the third week of May and I was sitting with my seven-year-old son at home, working on an online school assignment. My phone ‘dinged’ and I blinked in disbelief as I saw the message from my husband: ‘Pack up the house, we have one week to get out.’ We were suddenly propelled into a state of simultaneous loss, grief, excitement, thrill, and anger.

My first two children, now seven and five, were born in Canada, our homeland, while my third child, now two, was born in Texas. For the last few years, I’d yearned to raise my children with ‘Canadian identities’. In the USA, we greatly benefited from the kindness and care of our big-hearted neighbours, friends, teachers, and church family but living under the constant fear of my family being killed or injured in a shooting (in 2019 alone, 37 people lost their lives in mass shootings in Texas) began to take its toll. This was compounded by a deep horror around what I perceived to be people’s gross desensitisation to this violence, the profound polarisation and disparities of socioeconomics, racism, nationalism and the structure of the medical system being solely based on one’s employment status. It was all just too much for me. I wanted out. Well, be careful what you wish for as the Universe/Creator/God, can be quite literal.

Shortly before Covid-19 hit, my husband decided he wanted a career change. I happily gave up my 20-year career as a child welfare and hospital social worker to invest in my own family life. I wanted to show my husband support as he showed me in that decision so I told him to go for it.

Unfortunately, the timing could not have been worse. We were filled with dread. During a time of mass layoffs and business shutdowns, how could my husband ever find a job? A few months later, he was able to secure a good position with a reputable company. As a Canadian citizen working in the United States, he simply needed to take his visa papers to the border for processing. But in accordance with President Trump’s ‘Keep America Great’ mandate to prioritise jobs for American citizens, my husband’s application was rejected. He was told to leave the country within one week. As he had travelled to Canada and, due to American’s own quarantine rules couldn’t leave the country for at least 14 days, our departure date was then approved for three weeks later.

The days blended into the nights as I furiously purged and packed our 3,800 square foot house we’d built a few years before. Yes, I wanted to leave America, more than anything, but not under these terms.

Settling into our Canadian life has been difficult. My husband was not able to sort out his work visa and we have been without an income since March. We receive some financial help through the Canada Emergency Response Benefit programme, enough to buy minimal groceries every few weeks. Canadian employers are not in a hurry to hire during a pandemic. We are swimming in debt and our personal belongings are in storage in Texas. Our house still waits for a buyer. We have no transport because we cannot bring our vehicles up to Canada. Presently, we live in a tiny townhouse owned by my husband’s uncle, who just informed us that he would like his space back. We have a plan but it entails burdening more family members.

Part of me is at peace despite our dire and humiliating circumstances. I found an amazing medical team and have already seen them twice. In America, this would have cost us several hundred dollars. People of colour in America are three times more likely to be infected by Covid, five times more likely to be hospitalised, and 1-2 times more likely to die from Covid (and at younger ages) than Caucasian people. You have a better chance of living through an epidemic if you live in a country with universal health care, don’t kiss a lot of people when you say hello or goodbye, don’t have to choose between food and health care, or, like President Trump, have access to an unprecedented level of care, day and night, have access to experimental treatments not available to the average citizen, have unlimited health care practitioners at your disposal and helicopters to transport you to hospital. The US has the world’s highest cumulative number of Covid cases to date.

Covid has taught me to live in the moment. My children perceive a situation based on my cues so I need to remain imaginative and upbeat about this ‘adventure’, no matter what.

We have slowed down, focused more on reading, walks, silly games and outings to the stunning parks of British Columbia. Coming home to the mountains, greenery and water has been healing. This period of life will hold many stories to tell my children later.

Arborist Dave Dennis is originally from west Dorset. He’s been in Nelson, New Zealand, since 1 March with his partner Megan McGovren.

Lockdown level 2 was lifted a couple of weeks ago and the country has returned to some sort of normality. Jobs, however, are more scarce and talk of future recession is a hot topic. Borders are shut to anyone without NZ citizenship and a two-week quarantine is in place which looks likely to continue for the foreseeable future. People seem more aware, verging on paranoid about the odd sniffle. I think with summer on its way the general mood in this area is one of optimism but we have seen how quickly this pandemic can re-emerge. Overall I feel lucky to be in a place which as a result of its geography and demographic seems to have a fighting chance against Covid 19.

Sports reporter Alan Nixon was born and brought up in Scotland and has lived in Warrington for 32 years.

During lockdown, if you see a scary man in a helmet riding a bike uncertainly that will be me. Need to keep up with granddaughter Isla somehow and keep the weight down. Covering football for The Sun is much the same until match day. Your own private game every weekend. Then a chat with the manager on Zoom. Bizarre. The second wave won’t be easy if you can’t go out at all. Then it really will be too long on the sofa, watching TV and betting too much. My main fear is children missing out on school and people getting out of the habit of leaving the house. It is an anti-social disease. I would probably emigrate but I hear there is a new series of Brassic coming. Simple pleasures.

Neville White is originally from Chard. He lives near Frankfurt and is global analytics leader at DuPont. He has been in Germany for 25 years.

Back in March, I set up my computer in the cellar and started working from home. I was soon able to conduct meetings as effectively as ever and have now grown to love the arrangement. I’m using the extra time at home to advance my skills in music theory, data analysis and German grammar.

We can’t complain here. Infections remain relatively low, restrictions are reasonable and Kurzarbeit has saved many jobs. Losing our Christmas Markets has been painful but we’re able to meet up with family and friends. Christmas will be fine. Germans always find ways to celebrate.

We held our own family Oktoberfest in the garden this year since Munich was cancelled. It was cold and a little rainy but everyone had fun.

New Covid cases are increasing across Europe as we head into winter, but fatalities remain low. I’m optimistic that significant improvements will be made in 2021.

Bridget Strange lives in Boca Raton, Florida. Originally from South Petherton, she and her husband, Mike, have lived in America for 52 years.

Florida was one of the critical states just a couple months ago, but things have vastly improved. Masks are still very much encouraged although fines are no longer imposed. I can see things going downhill come November and December. Our Christmas will be the same as always, having our daughter and her husband here who also live in Florida. We don’t go out as much as we used to and we’re certainly not ready to hop on a plane. The majority of people are still being very cautious. We are lucky being retired, having no jobs to lose and no young children to care for. I see more layoffs looming. It’s been an horrendous year what with the pandemic and the protests and riots. And now our President has been in hospital with Covid, after downplaying the situation. Our election is imminent. Given the fact Mr Trump is dead set against mail-in voting as he says that will be rigged and has not committed to bowing out peacefully should he lose the election, who knows what the future holds. It’s definitely a very divided country.

Housewife Mrs Leena Sinha has lived in New Delhi for more than 26 years.

It was March 25 when the lockdown started and since then we have been living under a constant state of apprehension. We packed our homes with all the things we might need, but always it seemed that some necessary item might have been overlooked. We lived in constant fear of getting the disease and even more frightening was the prospect of being sent to government hospitals and quarantine centres since you would be in sort of prison where you might not even get to see your family for two weeks.

After July 18, the government began lifting restrictions and people resumed their day-to-day activities, albeit with masks and sanitisers. People who were infected were allowed to live in their homes in self-quarantine.

Now it seems people are not as perturbed by the disease and have resumed their social lives as was normal before lockdown. In coming months, people, especially the younger generation, are looking forward to celebrating our festivals like they used to. This trend will continue with our government deciding to open schools and colleges again. Amidst all this, we are still seeing a rise in the number of people affected by the disease, which will continue until there is a vaccine.

Distiller Tim Stones, who is originally from Bridport, has lived in the Northern Beaches, Sydney for nearly four years.

In New South Wales, we’ve been extremely lucky. With a total of 4,250 cases we’ve not been locked down as severely as Victoria, which with 20,237 cases was hit hard.

Post-lockdown, life is getting back to normal. Except for social distancing measures, capacity limits in hospitality venues, and masks on public transport, everything seems normal again. Twenty people are allowed to visit your household, so that shouldn’t impact on Christmas plans. Except for Victoria, state borders are opening and internal travel is starting again so families will be able to see each other.

Looking back on the government’s handling of the pandemic in general, I’ve been impressed. It’s not been perfect, but when I see how other countries have handled it, I’ve considered myself very lucky to live here.

In Australia, the future looks positive, albeit heavily sanitised. Aussies are a resilient bunch and, for the most part, are doing their bit to help get life back to normal as quickly as possible. Some people still have a lot of toilet paper to get through though.

Babette Schriks lives in Eindhoven, Holland, and is a professional in learning and development within organisations.

Besides all the negative aspects of coronavirus we experienced a positive one. During the first lockdown it seemed people got out of the rat race. Everything and everybody slowed down. There were restrictions that applied to everyone, no dining out in a restaurant, no theatre, bar, sauna, etc. Rich or poor, we were all in this together. For many people it felt like everyone was equal and there was a sense of comradeship.

Now we are heading for a possible second lockdown and my feelings are mixed. Of course, the economy will suffer hard from a second lockdown. But the camaraderie has diminished. Some people are opposed to the government’s measures which leads to polarisation. One is shouting louder than the other. I will miss the social interacting with friends and family. But on the other hand, the tranquillity of a second lockdown and the feeling of equality due to the restrictions is very appealing.

University lecturer Louise Matthews lives in Auckland, New Zealand.

The last few years I’ve somehow found myself flying back to Bridport for New Year’s Eve as well as catching up with friends and family. But this Christmas—our summer hols—I’ll be making the most of the situation and travelling around New Zealand to revisit some amazing spots, last seen when I lived here 17 years ago. That’s because while Kiwis are still free to come and go overseas, you still have the mandatory fortnight hotel quarantine on return. I am in no rush. There are places here I haven’t seen since the 90s. After lockdown, Kiwis have enthusiastically taken to domestic tourism with renewed appreciation.

Christmas for me will involve a combo of beach, swims, great food and a horse ride in the forest.

I feel very lucky to have a job that could continue, thankful for good health while Covid knowledge still develops (especially as family and friends overseas have all suffered); for the reminder of what’s important; beautiful surroundings to exercise and have peace in, and thankful for how New Zealand approached this. I am incredibly thankful and lucky to be here.

UpFront 11/20

Having a last look over this issue before it goes to the printer, there is a lot to take in. From Margery Hookings’ communication with local people overseas to Samantha Knights’ explanation of modern slavery, as well as articles about the local area and information on fascinating exhibitions and talks, there is a healthy image of local diversity. There are welcome signs of creativity, as well as humanity—perhaps even a snapshot of continuity in the face of such upheaval in our world. Back in April, in the early days of lockdown, I asked some friends on a zoom call whether they were concerned by the personal intrusion posed by the idea of track and trace. I had been told by an epidemiologist that a strict track and trace system could help stall the spread of coronavirus and make it manageable until treatment and vaccine options were more advanced. He had pointed to the success of South Korea in stalling the virus using personal information gathered by whatever means possible. As many of those on the zoom call were seasoned journalists, I expected at least a little indignation at the potential trawling of personal data. But the shouts of incensed outrage were nowhere to be heard. Instead, one simply answered ‘they already have all that data, what’s the difference?’ There was a little shrugging of shoulders and a conclusion that voluntarily making personal information available to authorities—who may or may not allow it to be used for purposes other than that for which it was obtained—would not be popular. I was reminded of their response when reading Paul Lashmar’s book, Spies, Spin and the Fourth Estate, before talking to him earlier this month. A fascinating account of the history of the intelligence services and how they have used and abused the media, the book also offers insights into some of the many activities agencies are alleged to have been involved in from the Great War to the current day. Paul talked to me about ‘huge warehouses full of servers’ with data on everyone in the country. His concern wasn’t so much that data had been collected, though that is a concern, but that there is little accountability and oversight on the organisations that are collecting it. With Google, Amazon and the Facebook group of companies gathering and utilising data that can help them manipulate people’s buying habits—and possibly their social and political activities—it’s not surprising that we may be becoming immune to the collection of personal information.

Louisa Adjoa Parker

My Dad came from Accra, Ghana, to study nursing in the UK. He and my Mum, who is white British, got engaged not long after their first date, much to the disapproval of Mum’s parents. They opposed the marriage because of the cultural differences as they saw it. However, much to my Mum’s delight they turned up at the wedding, and totally accepted us kids when we arrived, although they were worried for us with good reason, because life was sometimes going to be tough.

I was born in 1972, the eldest of three children, in Doncaster, Yorkshire. Memories of early childhood are hazy, but at times it was challenging. There was domestic violence in my family, and in the community overt racism was all too common. It was a very difficult time for black and brown people everywhere.

Our next home was in Cambridgeshire, near Huntington. At that time, my English grandparents moved to Kingskerswell in Devon to retire. I have many happy memories of childhood holidays there. When I was seven, my Mum pulled me and my sister out of school because she felt the headmaster was prejudiced, and as a primary teacher herself, taught us at home. I loved the process of learning; I especially enjoyed learning French and English. I loved reading Enid Blyton’s stories, and wrote my own stories as a young child in a similar style. Words were an escape route for me. The self-discipline that came from learning alone at that young age has stayed with me and makes writing at home perfectly enjoyable.

I decided I wanted to go to school, so aged 11 went to Hinchingbrooke Comprehensive. I was keen to integrate and make friends but found it difficult having been out of school for the last four years. Knowing what to wear, with so much peer pressure at that age was tricky. I had to reinvent myself quickly, something I’ve often had to do throughout my life.

When I was 12 my parents split up, something I was relieved about. Mum moved us to Paignton in Devon to be near my grandparents, but sadly, only six weeks after we’d moved my Grandad died of a heart attack, and my Mum really struggled to come to terms with that. Although I was upset, I coped with the loss, and began to enjoy living in Devon, up to a point. I felt safer without my Dad around, although I was conscious that racism was a huge issue in Torbay, perhaps worse than where we’d lived before as it was less multicultural. I was a sociable kid, and I made close friends with another girl my age in our street who stuck up for me. The local boys, however, treated me and my siblings very badly.

Although we lived in Paignton, I went to a Steiner School in Totnes. Paignton was a bit rough, but things were different at school. I had to reinvent myself again as a ‘hippy’ to fit in, so I got rid of the plastic earrings, and wore baggy jumpers and leggings. I loved the two years I was there, although it seemed a much longer part of my life, and it felt almost like another family. There was no uniform, we called the teachers by their first names, played recorders and did weaving. We did something called Eurythmy, a strange dance therapy pioneered by Rudolf Steiner.

But then the school had money troubles, so my whole class had to leave. That was traumatic for all of us, but I had been lucky to have had a teacher, Ian, who had seen some potential in me and encouraged me. I made two life-long friends there. My next school was King Edward VI Community College in Totnes. Another major reinvention for me after the Steiner School, and I struggled with the rules, trying to keep the identity I’d adopted in the last two years. I insisted on wearing dangly earrings, and would hand them over stroppily to the teachers when they caught me breaking the rules.

When I was 15 I began to get into drugs and alcohol. It was quite widespread in Totnes at the time, and I gravitated towards other kids who were a bit dysfunctional and like me had had challenging lives. I was quite depressed, and I had very low self-esteem. As a mixed-race kid in the South West I felt I didn’t belong to any particular group, and my face didn’t look right against a rural landscape. I did my best to keep my education together, and despite being stoned in one exam managed reasonable grades at GCSE. I began to move from smoking cannabis to harder drugs.

When I met the man who became the father of my oldest daughter, a new age Traveller, I moved into a squat in Totnes, which was above the Job Centre (handy, fellow squatters joked, for signing-on), although at the age of 17, I couldn’t claim any benefits. There were criminals and addicts passing through the squat. My education inevitably suffered and I was kicked out of Sixth Form. I think these days there would be more support for someone in my situation, a troubled kid, but despite my best friends begging the teachers to let me stay, I had to leave.

Soon after that, my boyfriend went to prison, and I got a job at a restaurant, and sofa-surfed, but when he came out I slipped back to the same lifestyle. We were homeless, and lived in a bender by the river, amongst other places, then moved to the Forest of Dean where we first lived on a bit of carpet under a tarpaulin. In due course I found I was pregnant, and realising this life couldn’t continue, I went back to live with my Mum. Before my daughter was born, I got my own flat. I knew that because I had the responsibility of a child, I had to turn my life around. I didn’t want her growing up in such a chaotic lifestyle.

My Mum met another partner and together we moved to Lyme Regis, in 1992. I was seeing my daughter’s father occasionally. When she was two he died of a heroin overdose. I felt safer in Lyme than I had anywhere else. I was a teenage single mother, and I went on to have two more children there. I’m aware I was judged about having children with different fathers, and for being a single mum (and being black). But I decided that although I’d made mistakes in my life, I was going to be the best mum I could be. Life was tough on my own with three kids, but one day I had a sudden realisation that instead of being a victim, and things happening to me, I could do something about my life and make positive changes.

A friend paid for me to do a distance-learning Sociology A Level with Weymouth College, and I found I absolutely loved the subject. During the exam, I had to rush out halfway through to breast-feed my youngest daughter, but I still got an A! I began an Open University degree in Sociology, and then finished the degree at Exeter University. It was like a dream come true, something I never thought I was capable of. Having to organise my kids’ school day, and get myself to Exeter for lectures for two years, was difficult to say the least, but in spite of the challenges, the experience was fantastic. I couldn’t have done it without the support of my good friends Maisie and Lisa, who helped with the children.

As part of my degree I studied racism and migration, a subject which changed my life. I found out there was a gravestone of an 18th century black person in Devon, and I’d been thinking I was one of the first! People often think immigration started with the Windrush, but the Romans brought black people with them to England; people from all over the world have been coming here for thousands of years. I began imagining ghosts of Africans in West Dorset, and, wanting to tell their stories, I co-wrote a book and exhibition with Lyme Regis museum called Ethnic Minorities: Lyme Regis & West Dorset, Past & Present. That was my first heritage commission, and from there I’ve written lots more about the experience of local ethnically diverse people for other projects.

I’d also started writing poetry whilst I was at university, and my career as a poet has gradually unfolded. As well as my writing and associated workshops and talks, I now also deliver equality, diversity and inclusion work. I have three books in the pipeline due for publication in the next year: a collection of short stories, a poetry pamphlet, and a coastal memoir, with Little Toller Books, a Dorset publisher of books relating to nature.

When I was 36 I met my husband, Pete, who’s been a great stepdad to my children, Keziah, Jess, and Alicia, although adjusting to life as a ‘blended’ family was hard for all of us—the children were used to just being with me. I have three beautiful grandchildren, Maya, Leila and Harrison, and another on the way. With my family nearby, and so many friends and connections to the South West, with its stunning sea and landscapes, I finally feel this is where I belong.

Screen Time

Go to the cinema. They are open again. The Plaza has reopened in Dorchester and so have the local Odeon and Cineworld cinemas. They all have COVID precautions in place and you will need to wear a mask. You just have to remember to breathe slowly during the scary scenes or your glasses steam up!

Death on The Nile (2020) is on general release. It is Kenneth Branagh’s second outing as Agatha Christie’s Belgium, not French as he continuously reminds the world, detective, Hercule Poirot. Fantastic cast list. It is filmed on location in Egypt so it could be the perfect escape from early onset of winter blues.

Second classic remake of the month is the release of a new adaptation of The Secret Garden (2020). This has been adapted by the go-to screenwriter of the moment Jack Thorne whose credits include A Christmas Carol and Harry Potter and the Cursed Child for the stage, Shameless, Skins and His Dark Materials for TV and Wonder, Aeronauts and A Long Way Down for cinema. The Producers are the ones behind the Harry Potter films and Paddington and know how to find great young actors. It looks like they have found a new star in 15-year-old Dixie Egerickx who plays the lead part of Mary.

Here are a few new digital releases to be watched from the comfort of your sofa.

Rebecca (2020)by Daphne du Maurier has been adapted for the screen numerous times most notably by Alfred Hitchcock. Late October 2020 sees the release of British directors Ben Wheatley’s version on Netflix. I am eagerly looking forward to Kirstin Scott Thomas’ interpretation of Mrs Danvers.

Black Box (2020) is the first of a season of horror films Amazon have made with the award-winning producer Jason Blum, who brought you Whiplash, Get Out, US and Black Klansman. Black Box has no reviews yet but looks well worth a look.

Relic (2020) available on Amazon Prime is the film of the month to watch if you really need to frighten yourself. A haunted house movie tackling the theme of dementia.

Casablanca (1944) on BBC iPlayer is however a real gem.

“This great romantic noir is still grippingly powerful: a movie made at a time when it was far from clear the Nazis were going to lose.” Peter Bradshaw. The Guardian (2012)

If you have never seen it make a date to spend an evening with Bogart Bergman.

“Play it Sam. Play As Time Goes By!”