A very wealthy businessman once told me that inside all highly successful self-made businessmen and women lurked a ‘sliver of razored ice’. He claimed that it helped them to overcome any pangs of emotion or conscience that might interrupt their drive to succeed. As far as he was concerned, it was the key element that had helped him to make millions of pounds over his career. Considering the thousands of neurological and psychological studies done to try to understand why some people follow their conscience more than others, it may have been a simplistic description, but the ‘ice’ in the heart is a powerful image just the same. Despite his simple characterisation, we do appear to be living in an age that favours material gain over social community, and many say that the potential for an equitable and therefore more sophisticated society is looking harder to achieve. But according to research published by psychologists from the University of Würzburg and the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, all may not be lost. They have confirmed that mental training can effectively cultivate care, compassion and even altruistically motivated behaviour. They believe that what they call “prosocial behaviour” is at the heart of peaceful societies and is, therefore, a key to facing global challenges, whether dealing with climate change and its consequences; the refugee crisis or the unfair distribution of wealth. Anyone who has benefitted from hypnotherapy or cognitive behaviour therapy will be familiar with the theory that humans have the ability to change their habits. I’ve been an ex-smoker for nearly twenty years thanks to hypnotherapy and I can vouch for the benefits that can be achieved by sensitive and cooperative manipulation of the subconscious. To test their theories, the scientists ran meditation-based mental training in socio-affective skills such as compassion, gratitude, and prosocial motivation. It turned out that, after the practices, participants were more generous, more willing to help spontaneously and donated higher amounts to welfare organisations. Many decades ago we might have imagined a 1984 scenario with mass brain-washing. But according to the scientists, cultivating these effective and motivational capacities in schools, healthcare settings and workplaces may be a useful step towards meeting the challenges of a globalised world and moving us towards global cooperation and a more caring society.

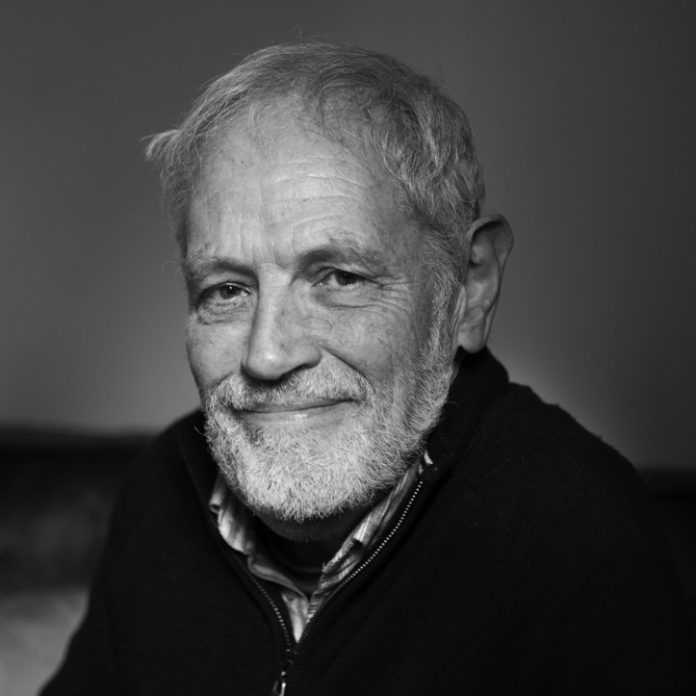

Philip Browne

‘I grew up in Sligo in the west of Ireland, the eldest of three children, two boys and a girl. I was one of a small percentage of Protestants in the town where my Dad was the Church of Ireland clergyman. Sligo is about the same size as Dorchester. We lived in a big eighteenth-century rectory, which had nearly three acres of garden. It was huge and surrounded by a ten-foot wall. As the only Protestant kid in that part of town and living behind these huge walls it was years before I got to know any of the local kids. I did meet other kids that went to our church, but in those days, and to a large extent now, schools were set up on religious lines, so I went to the very small Protestant junior school and then to Sligo Grammar.

The front gate of the house was like a little castle gate, and if I ventured outside of the house, local kids would shout ‘Proddy dog’ and throw stones at me—so I didn’t go out much. But then one day it was snowing and some boys came and threw snowballs and I threw some back and we got talking. My mother let me invite them in, and of course, as our garden was more of a jungle because it was unmaintained, we had a great time playing there. But then when I was 15, my parents decided that it might be better for my career to have O levels and A levels than the Irish Leaving Certificate, so I was sent off to boarding school in the North. Which as a boy of 15 I wasn’t too pleased about. They sent me off to Enniskillen in County Fermanagh, to a boys’ boarding school called Portora which included Samuel Beckett and Oscar Wilde among its past pupils.

I didn’t do as well as I had been doing in the Irish system but it was an education! I had never seen an Orange parade or encountered such hardline attitudes. Because I came from the South, the boys called me a Fenian. Anyway, despite not doing that well, it was enough to get into Trinity College Dublin where I did a degree in General Studies. One year I shared the room that Oscar Wilde had lived in when he was there. I had heard that Wilde had painted green butterflies on the walls of his room and of course after a few drinks one night I decided I wanted to have a look at them. It was a disappointment. Peeling back layers of wallpaper revealed nothing.

My main interest really was drama, so I spent the whole time at Trinity in the University theatre doing one play after another, which was something I had discovered I liked while at Portora. There were many of my fellow students who went on to great success. At one point I was in charge of putting the programme together for a show and when it was printed discovered that one of the main performers, fellow student Chris de Burgh’s name had been left out. Those were in the days, when he was playing small gigs in Captain America‘s burger bar in Grafton Street.

I did the postgraduate teacher training diploma in the late sixties early seventies—an eventful time. I was in Dublin when the British embassy was burnt down after Bloody Sunday. Then I got a placement in a school called Mountjoy which, during my time there, became Mount Temple. I came across a few characters. One of the 12 year-olds I taught English to was called Paul Hewson who now seems to be better known as Bono of U2. A friend and colleague was Dick Spring who later played rugby for Ireland and then went on to a career in at the top of Irish politics. We had some great craic over those years.

But of course, the curse of sectarian education meant that there were very few jobs in Irish Protestant schools at the time, not that I’d have had any objection to working in a Catholic school. It just wasn’t an option. So I decided to look for jobs in England. I got an interview in Nottingham and also in a place called Puddletown, which I’d never heard of. So I went into the British Rail office in Dublin and asked them where it was. They were as clueless as me but found it on the map. I was offered the job in Nottingham but having lived in a city for the past six years, I wanted to try life in the countryside. So I went to the interview in Puddletown, which at the time had the smallest secondary school in the England.

It was in the most fantastic setting, though the interview was eccentric, to say the least. The first question was “Mr Browne, can you swim?” to which I was tempted to answer “no I came by boat” but it turned out they had just built a swimming pool and needed someone to teach the children to swim. As it happened, I got the job to teach English and Drama but after one term I had enough of village life so I bought a small car and found somewhere to live in Dorchester.

Then in 1980 when they changed the school system, I moved to Dorchester Middle School. I stayed there as Head of English until 1985 when I was seconded to a post-graduate course in London for a year, learning how to promote reading and the use of libraries etc. It was this that led me to what I do now. One aspect of the course was to write a piece on local history, and I didn’t want to do the obvious things like the Romans or Thomas Hardy. So one day my next door neighbour told me he was going to Worth Matravers that night to stand on the cliffs. This was on a bitterly cold January night, and my first reaction was “Are you mad? It’s freezing out there!” Then he explained that it was the 200th anniversary of the shipwreck of the Halsewell East Indiaman and that he and a few friends planned to mark the occasion by going out onto the cliffs at midnight.

So I set about researching this shipwreck. It turned out that in 1786 this huge ship was wrecked off the Purbeck coast. Of course, there were many ships lost on the coast of Dorset, but this became a very big sensation at the time, in part because the local people of Worth Matravers managed to save lots of the crew. That was remarkable enough, but it was subsequently found that there were some young ladies on the ship who had all drowned along with the Captain. The story of why they were there was fascinating. The whole event caused a huge public outcry and also triggered an outpouring of artistic endeavour; there were poems, drawings, music and paintings by well-known artists. There was even a theatrical performance in honour of the event. Anyway, I did this for my course and when I got my assignment back it was the best mark I’d got all through the whole course and the tutor said why don‘t you work this up into a magazine article—which I never did. Instead, I decided to put it on hold as something to come back to when I retired one day.

I then went back to teaching. My wife Beth and I had had the first of our two sons Peter and Christopher at this stage, and soon after that, I got a job with the local authority. I became an Education advisor for the Education Department at Dorset County Hall. It was around the time when the national curriculum was coming in, and there was lots of training and retraining for teachers. It was a fantastic job because my role was very flexible. I was very keen on children’s literature and encouraging kids to read. So I used to run an annual event where I would invite leading authors to come down to Dorset for a day so teachers could meet them. Over 15 years there were many but I remember Allan Ahlberg, Michael Morpurgo and Shirley Hughes particularly. I also had responsibility for organising training for support staff. In those days there was no real career path for support staff, but over the years we put in place induction training, advanced training, NVQs and a path on to a degree course if they wanted. For many years, I was also a school Governor at St Osmund’s where my sons went to school, which was a great way of keeping in touch with school life. It’s all very well running courses, but unless you go to a school every now and then, you can get a bit isolated from reality!

So in 2010 when I retired, I wondered what I was going to do. I didn’t play golf, and I couldn’t just go to the pub every day, so I came back to the idea of writing about the Halsewell. I then spent a couple of years researching it and found out loads of stuff that nobody had known about before. It amazed me that nobody had ever written a book about it. I discovered that Captain Peirce’s logbooks were all available and I went off to India to research some of the places that he had been. That was terrific fun. It was eventually published in 2016, and since then I have been travelling around giving talks to various groups from small local history meetings to U3A and Probus. Last year I was a speaker at the Goa Literary Festival and before that at the Chalke Valley History Festival where I dressed up in full 18th century Sea Captain’s outfit. It’s a very dramatic story, so I get great feedback from these talks. This year I won the Dorchester Literary Festival writing prize of £1000 and have decided to invest that in the initial research for another historical biography and I’m also working on a novel. Retirement’s quite busy really.’

December in the Garden

A recent acquisition of a new, old, bookcase has afforded me the opportunity to dig out some of my old gardening books. Having been forced to perform an emergency, spine re-glueing operation, on a small, green, volume—I couldn’t resist perusing the last chapter :-

“December—This month is a perfect blank, both for the flower and the fruit garden; except for collecting soils, making composts, preparing labels for names or numbers, sticks or stakes for tying up plants, nails and list for fastening them; and, in mild weather, for pruning the larger and more hardy deciduous trees and shrubs, &c.” : ‘Plain Instructions in Gardening; a calendar of operations and directions for every month in the year’, by Mrs. Loudon (1874).

This comparatively tiny book is dedicated to ‘J C Loudon, esq., by his affectionate widow’… and herein lies a tale.

Mr. Loudon was the leading gardening author, publisher and promoter of his day and Mrs. Loudon does explain that it is her husband to whom she “owes all the knowledge of the subject she possesses”. What she omits to mention is that she was already a published author, albeit anonymously, of an ahead of its time (1827) science fiction novel; ‘The Mummy!: or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century’.

Although an established writer, as well as the founder of the first gardening magazine, John Claudius Loudon died ‘in poverty’, no doubt having overstretched himself in all his numerous endeavours… Jane had been in this position before.

She first escaped penury, orphaned at the age of 17, by anonymously publishing that ground-breaking first novel. Jane had already swapped ‘Fiction’ for ‘Fact’, before the death of her husband when she was just 36, but her gardening books, aimed at a new, niche audience, must have been a real salvation for her. I think it is interesting to note that, unlike her original ‘Science Fiction’ book, Jane Loudon was able to publish her gardening titles under her own name—that was pretty pioneering and a sign of just how much times had changed since Queen Victoria took to the throne.

I’m sorry if that is a bit of a diversion away from more practical horticultural matters. I must admit that I’ve been struggling myself, a bit, with gardening lately, or rather the actual getting out of the house to do anything useful. Sometimes “a change is as good as a rest”, so spending time re-reading old books, as well as seeking out new inspiration, may be time well spent at this time of year when the garden is at its lowest ebb.

When conditions allow and getting out into the beds and borders will not lead to soil compaction or a muddy mess, this month does lend itself to a certain amount of getting ahead of the game. In the past, it was generally accepted that all herbaceous plants would be completely cut down by now, to just above ground level, and the shrubs and trees left in splendid isolation. One advantage of this is that it removes a lot of the hiding places that pests and diseases are able to survive the winter in—and that is still valid—but the general consensus these days is that it’s more ‘wildlife friendly’ to leave old stems and leaves in situ right up until spring is about to be sprung.

As with most things in life, there is a balance to be found and whether you are a complete ‘bare earth’ gardener, or a ‘relaxed messiness’ practitioner, depends on what you are growing and the kind of garden you have. A very formal garden, with well-kept lawns, clipped evergreens and strong structure, could be somewhat ‘let down’ by masses of brown herbaceous detritus and unruly stems diluting the ordered formality.

On the other hand, a garden with more ‘naturalistic’ aims would be a little pointless if the nature-friendly potential of the plantings is negated by a complete removal of all plant material for at least three months of the year. If your garden is large enough then the usual received wisdom, sometimes sticking to convention has its advantages, is to have your neat formal areas close to the house (no-one wants an unsightly ‘outside room’) and to graduate to a more relaxed, flowing, style in the more outlying areas.

Of course, if all else fails, then December is a good month to consider your garden and start making plans if you intend to make changes to its design and planting for the year ahead. The good news here is that if you want to impose more structure in your garden, in the form of a hedge or avenue of trees, then it’s bare-root planting season. As long as the ground isn’t frozen or waterlogged, obtaining trees and shrubs in their bare-root state is the most cost-effective means of obtaining them in quantity. Also, due to being soil and pot-less, they are able to be sent by post or courier so an internet search should yield any number of nurseries to provide whatever it is that takes your fancy.

I spotted recently, along a quiet local lane, a hedge consisting largely of ‘Snowberry’ (Symphoricarous albus) which was particularly stunning this year because the good summer had ensured that every stem was adorned with a cluster of fat, gobstopper-sized, berries. It was looking positively festive as if miniature snowballs had been artfully affixed along its length. It may not be so bountiful if trimmed in a more formal manner but, when allowed to keep its extension growth until late winter, it should provide a welcome bejewelling from leaf-fall until the birds consume its bounty.

As a shrub it’s a bit of a dullard, and horribly out of fashion, but the sight of all those little snowballs, bouncing along the lane, took me right back to my Primary School and the alluring white berries that caught my imagination, as a five-year-old, in what was left of the school garden. I think I might order a dozen bare-root specimens and weave them into my existing mixed hedge……….Happy Christmas to me!!!

Vegetables in December

At last, a month when there is nothing to sow! In the mild weather, our vegetable garden is looking good where we transplanted lots of turnips, rocket, Mizuna and lettuce as we gradually removed summer crops in September and October.

Roots are coming up beautifully clean, and we are wondering if the dry summer soil made it trickier for nibbling predators such as woodlice and slugs. In April an MW reader wrote in suggesting sowing carrots in pots in a warm greenhouse. They all came up in a week, and dibbing them into soil with a pencil meant I could get perfect spacing. They were planted under mesh and are now harvesting well, although seem more fanged than usual in our stony soil.

I might be repeating myself, but this year’s yields were all about water. If you had access to a huge water butt like mine, all was fine and yields great. Take care not to spend too much on laying leaky pipes for next year, as that will for sure make it rain heavily next summer!

Yields in the greenhouse were fabulous. For peppers even more than tomatoes, early February sowing gave ripe red peppers by July, whereas a late March sowing had loads of mainly green peppers by the time the first frost came. We brought the fruit into the kitchen, where they are going slightly soft but remain delicious when green, and some are still ripening and turning a beautiful red colour.

If you feel you have to sow something this month, try Aquadulce broad beans and Douce Provence peas indoors in a seed tray, they will come up slowly and can be transplanted outside in January—they’re less prone to vermin attack as plants. And why are Christmas trees so hopeless at sewing? Because they keep dropping their needles.

Gavin Wakley

Gavin Wakley’s father started Inthatch Ltd over 35 years ago, supplying materials to the thatching industry. He began by growing his own thatching straw on their farm on the Blackdown Hills but soon found that there was a demand for more thatching materials than he could supply. So, he started sourcing additional wheat straw from local farms and importing water reed from abroad. In 2012 Gavin took over the day to day running of the business, which is now one of the largest suppliers of thatching materials in the country.

Gavin had prepared himself well for taking over the company as he spent his working life following university immersing himself in imports and exports. To gain experience he travelled to Poland and Turkey working for businesses exporting materials such as pumice stone to timber and frozen vegetables. Then, for 15 years he lived in London working for Tate & Lyle, trading sugar in Africa and the Middle East, and latterly managing the raw sugar purchasing for their European refineries. But, eventually, or, as Gavin states, “inevitably, the call of the West Country became too strong”, and he moved back to his home ground with his wife and two young daughters, to take over the family business.

Now, Gavin enjoys being able to fit in family life around the business. The girls are 9 and 11 years old and learning to sail in Lyme Regis at the weekend, and Gavin has also taken up lessons. Back on the farm, he still uses traditional methods to grow, reap and thresh 125 acres of long-stemmed straw with vintage farm machinery which allows the straw to remain undamaged. And although travelling less than he used to, he visits the countries he buys reed from, to check on the quality of his stock, and is off to Ukraine in December. But it could be to Austria, Turkey or even China that he travels to. And with his determination to produce and source the best quality reed he can, he helps to ensure the future of thatching practices around the country.

Chris Staines

Named after the original Dorset dialect word for ‘cowslip’, The Ollerod, in Beaminster (formerly The Bridge House Hotel) has made quite an impact since owners Chris Staines and Silvana Bandini took it on in March this year. Locals are welcoming and clearly impressed with the new arrivals, to the extent that they turn up with handfuls of freshly picked sloes and blackberries from their gardens and hedgerows to give to Chris, whose domain is the kitchen, to see what he can create with their produce. Winning Restaurant of the Year, in Dorset Food, Drink & Farming Awards so soon after they arrived, the couple have hit the ground running.

Chris’s CV is impressive and speaks for itself, including nine years spent as Head Chef at The Mandarin Oriental in London. Chris’s interest and passion for Asian flavours was piqued when he went to David Thompson’s restaurant, Nahm, whilst living in London. He was blown away by the combination of so many different ingredients harmoniously creating perfect dishes. That’s not to say there is solely an Asian influence in the food he creates, as Chris embraces and incorporates flavour injections from around the world. It depends on what produce is available, what time of year it is, and most importantly, how he feels on the day. Together with his talent for creating memorable dishes and Silvana’s front of house skills, their customers feel rather spoilt by the time they leave The Ollerod, whether that be after lunch, dinner or a night’s stay.

A complimentary hobby, adding to Chris’s passions is gardening. He says, “it fascinates me to see how a seed can transform itself into something stupendous”. Chris has always managed to grow something wherever he was living – even if it was from the smallest and most unlikely of spaces in pots when he was in London. One of the first things Chris did when he got the keys for The Ollerod was head out to the garden and set up his raised beds, ensuring an impressive array of different leaves for his salads each day. Next year, when they have their feet under the table a little more, Chris will be heading out to an allotment in between service, to try to grow a greater variety of vegetables for the kitchen, all influencing his inspired dishes.

Riotous Behaviour

At this time of year, our streets become full of pixy merriment, especially after dark. However we are fortunate that we do not hear of the riotous behaviour or its causes, that was experienced in days of yore. This article is not about November 5th, fireworks or bonfires, although some towns in England have been known to have riots on this date, resulting from the religious changes after King Henry VIII and possible changes if the Gunpowder Plot had not been discovered.

During the Civil War between Parliament and King Charles I, many farmers and landowners were annoyed by the actions of the troops on both sides, as they invaded their property and took chickens and animals without payment. The Protestants also brought their horses into churches. As a result, an organisation called Clubmen evolved, a strong neutralist movement of yeomen and tradesmen. Cecil N Cullingford in A History of Dorset wrote that some of their banners were inscribed with “If you offer to plunder, or take our cattle, Rest assured we will give you battle”. They wore white cockades and held mass meetings on several hillforts like Eggardon, and Badbury Rings. At Badbury a lawyer read out proposals in the presence of “near 4,000 armed with clubs, swords, Bills, Pitchforks and other weapons”. At Sturminster Newton they drew up petitions to both King and Parliament. The King’s reply was favourable, but Fairfax for Parliament only offered good discipline for his troops. Cromwell encountered nearly 2,000 Clubmen on Hambledon Hill, “one of the old Camps”, and when they refused to surrender he sent in his troops and “killed not twelve of them, but cut very many and put them to flight”. Cromwell reported that many of them were “poor silly creatures” who promised to behave themselves in future saying they would “be hanged before they come out again”. Apparently, Cromwell locked up his prisoners for the night in Shroton church, screened them next day and released all except a few ringleaders including Thomas Bravell, rector of Compton Abbas “who had told them they must stand to it now rather than lose their arms, and that he would pistol them that gave back”. The Clubmen movement was dissolved and this revolt was ended.

After our victory over Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815 people thought that peace would bring prosperity, but cheap corn came in from the Continent and many of our farmers became bankrupt according to Cecil N Cullingford. Parliament passed the 1815 Corn Law prohibiting imports of foreign wheat unless the price of homegrown corn reached 80 shillings per quarter. Unfortunately, the resulting high cost increased the price of bread which hit everyone, especially poor people. In the meantime, all parish priests could do was to lead parishioners with the prayer “Give us this day our daily bread”. As a consequence, the Riot Act was read in Bridport on 29th April 1816 to a group described as “several hundred persons” by the national newspaper The Times and after a trial of ringleaders was held at Dorchester Assizes on Saturday 3rd August 1816. This report is taken from the research of our friend and now Joint Chair of Bridport History Society, Celia Martin.

Wages were particularly low in Dorset and many men returning from the Napoleonic Wars were unemployed. Memories of the French Revolution were still in the minds of many people who were concerned that something similar could happen here. There were eight arrests made of those considered to be the ringleaders of the Bridport Bread Riot, of whom three were women. As women, they were usually those who bought bread and could tell if they were being overcharged or if the loaf was underweight.

The youngest arrested was William Fry aged 16. He was charged with stealing an 18-gallon cask of beer from the cellars of Gundry & Co. of Bothenhampton which was taken up to the town on a dray with several other casks, aided by a band of others. Fry was not found guilty of rioting. But the beer may well have assisted in inflaming the crowds into action over three or four hours. They were reported as marching up South Street and into West Street attacking the windows of bakers shops and houses, the leaders carrying sticks and staves impaled with loaves of bread.

At the trial, John Toleman aged 21, was fined one shilling and sentenced to imprisonment for 9 months. He had been one of the leaders carrying a loaf of bread on a stave and encouraging people to riot. Elizabeth Phillips was accused of using threatening language to baker William Diment, who was called as a witness at the trial. It was reported in evidence that the dialogue between them ended with Elizabeth Phillips shouting “we’ll have your liver and lights before tonight”. She was found guilty “of unlawfully and riotously assembling together with a great number of other evil-disposed persons” and fined one shilling and sent to prison for three months.

All the accused, apart from William Fry, were found guilty of rioting. The punishment tended to be harder on men than on women. James Stodgell aged 21, who had been found responsible for breaking the windows belonging to baker John Thomas of East Street, was fined one shilling and sentenced to hard labour for 12 months. Jacob Powell aged 31, was also fined one shilling and sentenced to imprisonment for 12 months. Samuel Follett aged 19, was also fined one shilling and sentenced to imprisonment for six months. Mr Justice Park considered Follett’s behaviour was worse than the others as he had thrown large stones at the shop and dwelling house of John Fowler, a baker, breaking the shutters and demolishing the windows.

Hannah Powell aged 21, was fined one shilling and sentenced to imprisonment for six months. She had attempted to rescue one of the ringleaders of the mob who had been taken into custody by Jessee Cornick. Susan Saunders, aged 22 was fined one shilling and sentenced to prison for six months. She had taken part in the riot and attempted to assault Robert Turner who was acting as a special constable.

It is interesting to note how many of the prisoners were fined one shilling but with differing prison sentences.

Recently one of Bridport History Society members, Carlos Guarita, told us about a photograph he had discovered of factory girls standing in front of the gates of Gundry’s factory in West Street, Bridport, near the present Costa Coffee and Timsons shops. The title said they were striking workers. Carlos investigated further and found a reference in the Bridport News of February 1912 to a group of women “standing shoulder to shoulder”. It appears that new machines had been introduced to the factory and those working on them could earn more money than those using the old machines. Arbitration was at first suggested but was not immediately taken up until a meeting in the Hope and Anchor public house on February 1912 with Miss Ada Newton from the Federation of Women Workers. Miss Newton met Mr MacDonald of Messrs. Gundry and the strike was settled. A sum of £9 13s. was collected for the girls.

Ada Newton came down again for a social meeting at St Mary’s School Fete, when the women paraded through the town. So these demonstrations ended peacefully. Other photographs from just before the war showed a group of men in South Street near the present Malabar shop and also another with a group of men outside the gates of the Gundry works.

You will notice that these three stories become progressively less violent as the years progress. Let us hope that this is a sign of advancement and not just a fluke of my selection.

Carlos also discussed the photographers themselves as some of the photos bore the name Clarence Austen. On investigation, it appeared that he was working for W Shepard who had a shop at 45 East Street. Shepard died later in 1912 and Austen set up in his own shop, possibly where the Market House now stands. Carlos is himself a photographer and has produced a book linking the photographers and the “striking women”, Clarence Austen, the Photographer and the Wild Cat Women.

My thanks to William Holden, History Society Editor for his transcription of Carlos’ talk.

Bridport History Society meets again on Tuesday, November 13th in the United Church Main Hall, East Street, Bridport for a Members “Show and Tell “and member Geoff Pulman will introduce songs from the period such as Oh what a lovely war, etc. All welcome, visitors entrance £3.

Cecil Amor, Hon President Bridport History Society.

Time Shift

It’s happened once again. It happens every year at this time and we all know it’s coming, but the shock of the event is still deeply depressing. Nobody asked me about it or if I wanted it to happen. Nobody asked you or anyone else either. It just happens by itself every year on the last Sunday morning in October. Yes, I’m talking about putting the clocks back an hour—the most discouraging and gloomy signpost of oncoming winter and the ultimate full stop of what has been a glorious English summer.

So, welcome to a further six months of unremitting gloom (literally) with night falling at tea time, schools and offices closing down in the dark and dusk descending all too soon shortly after lunch. The only good thing? You just had it! It was that extra one hour in bed we got on Sunday October 28th. Big deal.

I realise that daylight saving and moving back one hour to GMT can be useful for farmers, fishermen and other folks who work out of doors in the very early morning, but there is a much larger majority of the rest of us who hate it. After work, I can’t come home to walk my doggie anymore as it’s too dark to see him. You can’t mend the wonky garage door or dig the onions or do anything outside because you can’t see what you’re doing. After school, children can no longer run around outside because it doesn’t make sense to play footie at night time and it’s unsafe to bicycle home. Also, according to at least one major insurance company, there are over 30 percent more home burglaries after the clocks go back. There really is no need of an extra hour of morning sunlight for a 21st century workforce. The UK is no longer an agriculturally based economy and we depend significantly less on heavy industry than we did a hundred years ago when the factory hooter would blast us awake in the dark so we could get to work on time and build lots more steel widgets and ships and stuff.

Furthermore, the act of changing the clocks itself is highly disruptive to our health and general well-being. Statistics even show a greater chance of car accidents and sickness when our body clocks are unsettled. And I (for one) become permanently gloomy and bad-tempered when forced to live in a state of winter obscurity. Books and newspaper columns have been written about the appalling effects of S.A.D. (also known as Seasonal Affective Disorder or perhaps better as ‘Seriously Awful Darkness’). Laboratory mice forced to live in total darkness apparently develop blue teeth. Rats become suicidal and depressed without any daylight. I know exactly how they feel…

And the worst part of it is that we’re responsible. The whole standard time thing is a British invention. We imposed Greenwich Mean Time on the world way back in the times when much of the world atlas was coloured pink and Britannia ruled the waves. The trouble is that—in retrospect—we made a hash of it and got it so completely wrong. We should have set the world’s time to one hour later—i.e. our current British Summer Time—which would have made life so much nicer.

I suppose it matters a bit as to where you are. If you live on the equator, days and nights are of equal length. Sunset is at 6pm all the year round regardless of whether it’s Christmas or high summer. Of course, if you’re in the far north of the country, summer evenings can stay light until 11pm, so it makes some sense to have daylight saving in say Nairn or Newcastle. But we live in the south of Britain in the Marshwood Vale, so we could simply keep our clocks one hour ahead all the year round. This means that the current time in Devon and Dorset would be different from Birmingham or Liverpool, but would this be a huge problem? No, not really. North and South are already poles apart mentally, so an extra hour apart wouldn’t probably make much difference.

Why stop there? We can all surely agree that we live in a very special and unique part of the UK. The whole of the South West has a distinctive identity that requires special treatment nationally. What better way to preserve our unique regional character than to live in a different time and mood from the rest of the country. If our fab new Doctor Who can organise Time to her advantage, then so can we. I propose we move our clocks forward one complete day to the new South West Time (SWT). For example, Cornwall, Devon, Somerset and Dorset will be living their Tuesday when the rest of the country and the whole of Europe will still be creeping through a dreary dark Monday. That way, we’ll always be one step ahead. Yes, welcome to the vibrant new exciting South West! Leading the way, ahead of the pack—we’re already in the Future before the rest of them even get out of bed in the morning!

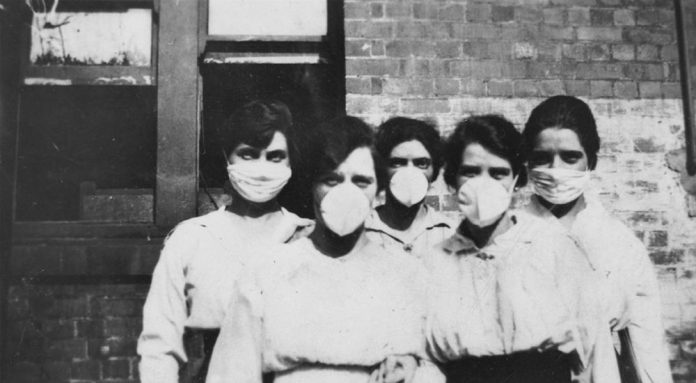

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic

The greatest global killer since the Black Death

As the First World War staggered towards its bloody conclusion 100 years ago this month leaving 17 million dead, the war-worn world suffered a second catastrophe. A lethal influenza pandemic swept the planet killing at least 50 million people. Most towns in the UK have fitting memorials to the war dead but the many who died from influenza are neither commemorated nor remembered. The Spanish flu, as it came to be called, was the greatest global killer since the Black Death. It is very important that its victims should not be forgotten and lessons learnt for dealing with future pandemics.

By June 1918, the fighting had been raging for nearly four years. Already worn down by the privations of war and the deaths of so many young men, people in the UK began to suffer the symptoms of influenza. Sore throat, headache and fever were typical but, after a few days in bed, people recovered and got on with life as best as they could. The illness had already swept across the US in the spring, reaching the trenches of the Western Front by mid-April leading to a brief lull in the fighting while troops recovered.

By September, however, a second wave of influenza surfaced, now in a deadly new guise. The virus was highly infectious sweeping through populations and quickly reaching most countries around the globe, its lethal progress assisted by the movement of troops to and from war zones. The majority experienced typical flu symptoms, perhaps a little more severe, and recovered quickly but, for about one in twenty of those infected, the effects were much more serious. Pneumonia-like symptoms caused by bacterial infection of the lungs were common leading to breathing problems and copious bloody sputum. Sometimes, the face and hands developed a purple-blue colouration suggesting oxygen starvation. This colour might spread to the rest of the body, occasionally turning black before sufferers died. Post-mortem examination revealed lungs that were red, swollen and bloody and covered in watery pink liquid; victims had effectively drowned in their own bodily fluids. There were no effective treatments, antibiotics had not been developed, and the death rate was high. By Christmas the second influenza wave had burnt itself out only for a third wave of intermediate severity to strike in the first few months of 1919. The pandemic came to be called “Spanish flu” because Spain alone, not being part of the war and so not subject to censorship, reported its flu experience freely.

In the UK, the Spanish flu killed 228,000 people in the space of about six months but this was a global pandemic and around the world the mortality was staggering. There were 675,000 deaths in the US and up to 17 million in India; overall the illness killed at least 3% of the entire population of the world. Unlike typical seasonal flu epidemics, deaths from Spanish flu were highest among 20-40-year olds with pregnant women being particularly vulnerable. If World War 1 had consumed the flower of youth, Spanish flu cut down those in their prime.

The sudden, widespread occurrence of a major illness with such high mortality caused huge disruption to daily life in the UK, especially in large towns. Medical services were overwhelmed as many doctors and nurses were on war service, funeral directors were unable to cope and there were reports of bodies piling up in mortuaries. The response of the medical authorities was poor, underplaying the gravity of the situation and providing little guidance; the newspapers, wearied by war news, were reluctant to give this new killer much coverage. Understanding of disease in the general population was rudimentary and a sense of fear and dread prevailed as people witnessed so many apparently random deaths.

In the West Country, the second wave of influenza killed at least 750 people in both Devon and Somerset and about 400 in Dorset but many thousands must have been unwell. Contemporary reports from Medical Officers of Health and local papers give some idea of how life was disrupted:

“In Lyme Regis, schools were closed for a fortnight in October 1918 as a large number of teachers, as well as children, were stricken down with the malady”

“The epidemic occurred when there was a great shortage of doctors and nurses across Devon and in the autumn of 1918 many cases succumbed before they could be visited; so bad was this in north Devon that, in answer to appeals from Appledore and North Tawton, two members of the School Medical Staff went to the aid of overtaxed doctors”

“Schools in Dartmouth were still closed in November 1918, social functions postponed and a Corporation soup kitchen opened to supply nourishing soup for invalids”

Given the high mortality and the disruption to normal society, I find it surprising that the pandemic was not commemorated and seems to have been forgotten quickly. Perhaps after four long years of carnage abroad and disruption at home, another horror was just too much, and the only way to cope was to forget?

But what was it about the 1918 flu virus that made it so virulent producing symptoms unlike any seen before and killing so many people? We still don’t know but scientists in the US have made some headway by studying the virus extracted from corpses of people who died during the second wave of the infection preserved in Alaskan permafrost. This showed, surprisingly, that the 1918 virus had a structure similar to a bird flu virus. This partly accounts for its virulence: its bird flu-like structure would have been alien to the immune system of people at the time. Because it also had the ability to infect human cells, it was a lethal vector of disease-causing, in some patients, severe damage to the lining of the respiratory tract leading to bacterial infection and pneumonia, engorged lung tissue and bloody sputum. A flu virus normally found in wild birds had acquired the ability to infect humans and the pandemic was the result.

Could history repeat itself? Could the world experience another lethal influenza pandemic? There is certainly concern among experts that this could happen and the Government recognises pandemic influenza as “one of the most severe natural challenges likely to affect the UK”. Current concern is focussed on two bird Influenza viruses circulating in the Far East. Since 2003, these have infected more than 2000 people and nearly half have died. Almost all the human infections have come from close contact with poultry or ducks but should one of these viruses change so that person to person transmission becomes possible, then we could be facing another major pandemic. How would we react? Our healthcare systems, at least in the developed world, are more sophisticated compared to 1918 and surveillance is better so that we should have early warning of the start of a pandemic. The UK Government has an Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy, we have antibiotics and vaccines to combat bacterial pneumonia and some antiviral drugs to reduce flu symptoms. There is still the likelihood that healthcare systems would be overloaded and perhaps our best long-term hope is the development of a universal flu vaccine to protect against all strains of the virus.

Philip Strange is Emeritus Professor of Pharmacology at the University of Reading. He writes about science and about nature with a particular focus on how science fits into society. His work may be read at http://philipstrange.wordpress.com/

Up Front 11/18

With the US mid-term elections due in early November, commentators have been busy offering opinions on which way the voting will go. The Republicans currently control both the Senate and the House of Representatives. The question is, will the Republicans retain control of the Senate and the House of Representatives? Or might the Democrats win one, or even both? Or will one take the Senate and the other take the House? It is important stuff, as controlling the vote in the House or the Senate dictates how easily a President can get things done. The result is also a good indication of how well the current administration is doing, although traditionally the incumbent does poorly in the mid-terms. However, this year, if you take social media into account, the man at the centre of US politics has had more exposure than perhaps all of the past Presidents combined, and not necessarily for all the right reasons. He has also been having a running battle with traditional media, claiming it is the bearer of fake news, especially when it takes him to task. All this amused me when I recently came across a magazine I was involved with in the mid-nineties. I was living in America, and we ran a cover story on the man we then referred to as ‘The Donald’. It wasn’t what you might call a long read, but it described him as having ‘a ripening disregard for the non-affluent’, which is ironic when you consider where his voting base lies. However, one of the key points put across in the article was how much Donald Trump was able to use the media to his advantage. He worked his business ‘in the eye of the public’ it said. ‘The more he did, the more press he got; the more press he got, the more he did.’ It also suggested his only vice outside of beautiful women was his addiction to seeing his name in print or on television. ‘It is a major reason for his success, as well as his problems.’ Considering this article was written in 1995, after the first time he had used the US bankruptcy laws to restructure the debt of one of his companies, it’s interesting to see his relationship with the media today. In those days he was said to have the ‘Midas Touch’. Now, with his every Tweet getting massive exposure, he plays the media as well from off the page as he did when he was their golden boy. There’s one comment in that article from over twenty years ago that is worth bearing in mind, regardless of the mid-terms. ‘Barring any unforeseen twists,’ it said ‘he will be around and bigger and better than ever. Just a reminder, “There’s no such thing as bad press.”’