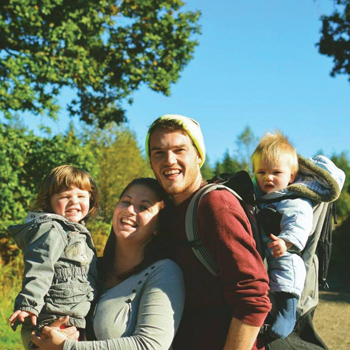

Every morning Simon makes the tea, five mugs of Earl Grey for his wife and four children – ‘all tea snobs’ he says laughing, as he sips at his coffee. Bundling everyone out the door to school, he just about makes it in time to open up the shop at 8.30am. Setting out the signs and starting the machines, Simon is the face and manager of the Bridport branch of Timpsons.

He started in 2000 when it was run as ‘The Menders’, training up in shoe repairs. Now, Simon does everything required in the shop from key-cutting, engraving, sending off the dry cleaning, mobile phone repairs and of course mending shoes. There isn’t much time to pause over the paperwork as Simon has customers walking in throughout the day, dropping off, picking up and asking for advice. He juggles the demands of his customers with completing the work at hand. Often he hasn’t got time for a lunch break as he is interrupted with a walk-in, which as he points out doesn’t matter as he’s usually eaten it by 11 am anyway. Lucky to have his wife Jody make his pack lunch each day, alongside the children’s, Simon saves his best smile for when he talks about her and how she cares for them all.

Not everything in Simons’ life is shoe leather and rubber glue though. At the weekend he morphs into a version of his earlier life and gets his DJ and disco equipment out. Previously a DJ at a couple of popular night venues in Bridport and Yeovil, Simon now runs Galaxy Discos & Karaoke, bringing the party to dance floors all over the county.

5.30pm brings the end of the working day at Timpsons when Simon locks up. He might stop for a cheeky half on the way home, needing a short break before the onslaught of four children hits him. ‘It can be a bit nuts some days, with one hanging off your leg, the other climbing onto your back, as soon as you walk in through the door’, he grins, clearly loving fatherhood, in all its guises.

People at Work

Brian Griffin to select photography for the 2019 Marshwood Arts Awards

One of Britain’s most influential photographers, Brian Griffin’s work has spanned many generations. He talked to Fergus Byrne.

At the opening of a new exhibition of some of his early work, photographer Brian Griffin looks slightly bemused at just how old some of the photographs really are. ‘There’s not an image on this wall that’s less than thirty-five years old’ he exclaims—an arm waving towards the many vintage prints that date from as far back as 1972. The exhibition, at the MMX Gallery in New Cross, is called Brian Griffin: Work and other stories and displays extraordinary silver gelatin framed prints including a ballroom dancer from 1972, and a 1974 image of the actor Simon Callow.

There are photographs from his corporate work in the early seventies, his visit to Moscow in 1974 and steelworkers in Broadgate in the mid-eighties, but what surprises many is the fact that his iconic photograph A Broken Frame taken at Saffron Walden for the cover of the Depeche Mode album of the same name is 37 years old. A unique vintage Cibachrome print, it’s available from the gallery for £6,800.

As selector for this year’s Marshwood Arts Awards, it is hard to find a more experienced photographer than Brian. The MMX Gallery exhibition also has signed copies of his book Brian Griffin Copyright 1978, which his close friend Martin Parr pointed out is the first self-published book by a photographer in the UK. Brian remembers how it came about: ‘There were no photo books around apart from, The World of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Bill Brandt’s Shadow of Light. It was just yearbooks—BJP yearbook, Photo yearbook, Zoom yearbook.’ He recalls seeing ‘wonderful pen and ink illustrations’ by the designer Barney Bubbles in the New Musical Express and wanting to work with him. They got together, and over a hazy afternoon in Brian’s flat developed the idea of using tiny, subtle line illustrations around some of Brian’s photographs. ‘I don’t know what made me feel so adventurous’ he says ‘because I wasn’t earning that much money then because I was doing editorial.’ He produced 500 copies, and very few of them sold at the time, but since then the book has become a collector’s item and sells for around £150.

He and Barney, whose legacy goes back to underground magazines such as Oz and IT became close friends. ‘He was like my brother’ says Brian. They worked together on many projects in the years to come until Barney sadly took his own life in 1983.

Growing up in the Black Country, Brian Griffin never really planned to become a photographer, but he did want to escape his job at British Steel. He compiled a rough photo album, ended up at Manchester Polytechnic, graduated with a diploma in 1972 and was soon commissioned to work for magazines like Management Today, Accountancy Age and Campaign. He had been hired by the late Roland Shenk, the design genius credited with transforming business-to-business publishing. Shenk once said that commissioning photographers like Brian Griffin was one of his “greatest achievements”.

As he was well experienced in photographing men in suits, when he took his portfolio to Dave Robinson, the one-time photographer who had helped set up Stiff Records, Brian was immediately assigned jobs to produce images for record covers. It was the post-punk New Romantic era, and there was no shortage of people dressing in smart suits for their debut albums. Brian’s first assignment, however, was to meet Graham Parker and find a way to photograph him looking like a gorilla. The result, shot near the Hayward Gallery on London’s South Bank, became the cover shot for The Parkerilla album.

The rest of Brian’s career in the record business reads like a who’s who of the music world. He photographed Nick Lowe, ‘He thought I was too arty and didn’t want to work with me’ and Peter Gabriel, ‘We didn’t work well together, although I must admit I was fond of him.’ Not much fazes Brian though, which was one of the reasons he could get such great shots. Peter Hamill from Van der Graaf Generator turned up with half a beard—he had shaved the left side of his face only, and Brian caught the idea perfectly.

Photographing Alex Harvey from the Alex Harvey band by the side of the Thames one day he turned away only to find Harvey—notorious for antics as wild as Keith Moon’s—had jumped into the river. ‘He ended up in Guy’s hospital as the Thames is so polluted!’

Album covers included Jona Lewie, ‘a true eccentric’ and Billy Idol, ‘I remember us bouncing around the studio like angels on pantomime wires’. For a Lena Lovich cover, he shot her as a silent movie star inside an empty stainless steel Guinness vat in the Park Royal brewery. He worked with Elvis Costello, Devo, Iggy Pop, Echo and the Bunnymen, Ultravox and The Teardrop Explodes. He shot single and album covers for David Essex, Kate Bush, The Stranglers, Chris De Burgh and The Psychedelic Furs.

One of his favourites was the cover for Depeche Mode’s Construction Time Again where he had the brother of one of his assistants standing on the side of a mountain in Switzerland wielding a massive sledgehammer. He was an ex-Royal Marine and ‘fit as a butcher’s dog’ said Brian. They even brought the sledgehammer from London to Switzerland where it landed on the luggage carousel with such a bang that customs men immediately descended on them. The final cover image, with the Matterhorn in the background, was breath-taking.

A photograph of Joe Jackson’s shoes for the cover of Look Sharp annoyed the singer because it didn’t show his face. He subsequently never worked with Brian again, but the shot is always in the top 100 album cover lists.

In 2017 he published one of the all-time great records of photography from the music industry during that era, with a book called simply POP. It includes photographs from all of the above as well as portraits of Vivienne Westwood, George Melly, Brian May, Queen, Bryan Ferry and George Martin—to name a few. Self-funded with a Kickstarter campaign, the book is one of more than twenty books of Brian’s photography. POP quickly sold out and is now hard to find at a decent price.

Other than a period from 1991 to 2003 when he concentrated on making films, TV commercials and music videos, Brian has consistently produced wonderfully creative photographs. However, he is acutely aware of the difficulty that success can bring. ‘The destructive element is success’ he says. ‘Success brings a lot of damage. I know for myself when I was very successful in the late 80s—I was the highest-paid photographer in Britain from about 85 to 91—it really was a destructive element.’ There was a point where clients exclaimed that he was ‘more expensive than David Bailey!’ But that didn’t stop them from hiring him. However, keeping his feet on the ground was hard. ‘I had to really fight with myself to stay on course’ he admits.

Despite his talent, there are times where clients see more than they hoped for. When commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery to photograph those involved in the 2012 Olympics, the client, along with the sponsor and the Olympic committee, didn’t want his image of Sebastian Coe to be used. ‘They felt he looked under pressure’ they told him. ‘Well of course’ exclaimed Brian. ‘He was under immense pressure.’ The photograph captures Lord Coe’s stress brilliantly and is currently displayed at the National Portrait Gallery.

Brian is looking forward to selecting work for the Marshwood Arts Awards and exhibiting alongside the winners in November. ‘Everyone loves to be exhibited’ he says. ‘Everybody loves to be selected. It brings a lot of credibility to the person that’s selected. It’s 100% positive in every way really.’ As a judge and patron of the Format International Photographic Festival, he understands the confidence that entering work for an arts award can bring, and points out how just looking at work to send in can take a photographer on an unexpected and often gratifying journey. ‘Maybe it’s an isolated image that they hadn’t thought deeply about’ he says ‘or maybe it helps them to prolong their investigation into that area.’

In 2013 Brian was described as ‘one of the most influential photographers over the last four decades’ and received the Centenary Medal from the Royal Photographic Society in recognition of a ‘sustained, significant contribution to the art of photography.’ In 2016 he was inducted into the Album Cover Hall of Fame.

People in Food

Unable to get out of bed in the morning until his lovely wife Sam has brought him a cup of coffee, Simon Mazzei blames his caffeine addiction on his Italian heritage. Chef and proprietor of the Olive Tree in Bridport, Simon’s restaurant specialises in Mediterranean food and a big welcome to all who walk in. A bustling, bright restaurant with staff singing their way through the day, interspersed with deliveries from local suppliers, all on first name terms and clearly happy to be there. Simon has created one big Olive Tree family, sharing his love of food, drink and people.

Working most of the days of the week in the restaurant, Simon flits between front of house and chef whites. He trusts his team implicitly within their roles and so fills in wherever needed, including pulling up his sleeves at the dishwashing sink. Once a week, Simon will lock himself away in his office, obligatory coffee in hand and catch up on the accounts and paperwork. Finally, at the end of his long days, he cycles home to North Allington where downtime takes precedence. This is often in the form of a glass of wine, “I prefer to drink a glass of something good than a bottle of something rubbish”, he declares. However, an essential part of the finale of Simon’s day is music. With a sound system in every room in the house, Simon loves to sing and dance out the trials of the day to the extent the glasses on the shelves are shaking with him.

Enjoying family holidays, often to Italy, Simon relishes showing his two girls his heritage. Whether it is visiting the village his father grew up in Naples, or enjoying the embrace of the ‘familia’ with their food marathons and enduring noise and chatter, each trip is a chance to taste new flavours and recreate them back at the restaurant. At home, Simon’s creative tastes often stray further afield. He’s currently growing kaffir lime leaves in his conservatory in order to get an authentic taste to his Thai Green Curry. Whatever Simon is making though, whether at home or in his restaurant, it is likely to be served amongst a background of music and warm smiles with a large scoop of ‘La Dolce Vita’.

Language or Lingo and Dialect

Perhaps I should not have included ‘Lingo’ in the title as I have since seen a repeat of Dad’s Army in which Captain Mannering rebuked one of his subordinates for using it. I think he thought it to be un-English.

Some years ago, when my wife and I listened frequently to the radio, one of our favourite programmes was presented by Hubert Gregg, previously an actor I believe. When he signed off he usually said ‘We will be together again in a Sennight’, that is in seven nights or a week. William Barnes wrote it as ‘Zennit’. Susie Dent writing in the Radio Times a few weeks ago said that around the 14th century ‘fourteen nights’ was shortened to a ‘Fortnight’. Also ‘Yestreen’ and ‘Yestermorn’ for yesterday evening and morning respectively and ‘Overmorrow’ meaning the day after tomorrow.

Time Team on TV once held a representation of an Anglo Saxon cremation with a eulogy read by archeologist Phil Harding, as his Wiltshire/Wessex accent was considered to be the nearest to the Anglo Saxon language. Time Team programmes are repeated on ‘Yesterday’ channel 19 around midday. Phil takes me back to my childhood with his ‘Ah’ or Aah’ and ‘Oh Ah’, the meaning changing with emphasis and number of ‘a’s’. Then there is ‘Ennit’ for ‘Is it not’ and the common ‘Yer’ for ‘Hear’. This is just what our local poet, teacher and minister William Barnes taught around a century ago. Listening carefully to Phil you can detect the words he has encountered more recently which are pronounced like ‘Oxford English’ among those of his childhood which are ‘Old English’. Some years ago I listened to Sir Bernard Lovell of Jodrell Bank fame on the radio and detected something similar between his technical words and his ordinary speech, which had a slight rural burr. He was born in Gloucestershire. This in no way detracts from their fame and achievements.

Back to my childhood I recall walking along the village street and encountering ‘Auntie’ Burh, who stopped us so that she could scrutinise my face and exclaim ‘Be y’en e a Amerr’ which being interpreted becomes ‘Isn’t he an Amor’, for our family likeness. ‘Amer’ being a common Wiltshire pronunciation of ‘Amor’. An American family historian told me of two Amor males who migrated to the USA, one was registered as ‘Amer’, the other correctly as ‘Amor’ and their lines have continued with the two separate names. ‘Auntie’ I may have mentioned previously as walking up and down the street saying ‘Anybuddyseed arr Annie annyof ee?’ as she had lost her wayward niece. ‘Auntie’ would also stop us in the street, saying ‘Don’ er Graaw’, that is ‘Doesn’t he grow’.

I recall when I was about five years old that my paternal Grandmother and associates would sometimes say ‘tis behopes’ it will not rain on washing day. I also remember ‘shrieved’ meaning shivering from the cold, when wet and not dried and ‘Shrammed’ meaning cold. This latter may be found in one of Thomas Hardy’s poems. Grandmother would also say ‘Lets have a Deck’ if she wanted a closer look at an object, or sometimes ‘Have a Deckoe’. My maternal Grandfather, a Dorset born gardener, would ask ‘Do you want a Hankercher?’ and showing plants would say ‘These’um’, but he would also say to his wife ‘Yes’um’! Flowers or nosegays were often ‘Tutties’.

Much of dialect is just abbreviation as ‘et’ in ‘I et it all up’ that is have eaten it all. Then ‘us’ instead of ‘or’, possibly a corruption of ‘else’ , e.g. ‘us it will die’. Other early interpolations came into the language, corrupted, from the army in India as in ‘Char’ for ‘tea’ and ‘charping’ for ‘sleeping’, from the Hindustani for bed.

Reverting certainly to earlier days people would say ‘Wur be gwain ?’, or ‘Wurst ‘gwain’ or even ‘Wurst be thee gwain’ meaning ‘Where are you going’. Also ‘N’arn o’ ye’ for ‘Not one of you’. ‘Ee’ can also be substituted for ‘Ye’. Occasionally I have heard ‘ook-um’ for job, or place as in ‘I don’t like this ook-um’. Also ‘caddle’ as in ‘I am in a bit of a caddle’ which William Barnes translated as ‘muddle’ but I wonder if it is a corruption of the phrase ‘A fine kettle of fish’ (kettle = caddle). The Wiltshire Regiment, now joined with another, previously had as its marching song ‘The vly be on the turmit’ that is ‘The fly is on the turnip’ which of course led to ‘Turmit o’in’ (hoeing).

As boys, if something was not working they would say ‘It won’t Ackle’ and my Mother would refer to a young girl as ‘laughing and Whickering’, a ‘Whicker’ being loud laughter, neighing. Ants were called ‘Emmits’ which is also William Barnes word for them.

Our local author, Sylvia Creed, in her book Dorset’s Western Vale also provides an extensive list of local words and phrases, some of which brought back memories, for example ‘Backalong’ for a while ago, ‘Bide quiet’ or ‘Bide quielt’ for be quiet, ‘Bide still’ for be still, ‘Bide yer’ for stay here. Also ‘Can’t be doin wie that’ for I can’t be bothered with that and ‘Crooped down’ or ‘Coopy down’ for crouched down. ‘Cuh’ for fancy that! Then, ‘Done up’ for ill, overtired and also ‘Don’t feel too special’ for I don’t feel well. ‘Well I’m blowed’ for well fancy that and ‘You’d better look sharp’ for hurry up. ‘Hapse up the gate or door’ for close or fasten. ‘Hummed and hawed’ for he couldn’t make up his mind. ‘Plimmed up’ when wood is swollen by water. ‘Skew whiff’ crooked or out of line. ‘Trig it up’ for prop up, e.g. a gate or door. ‘A month of Sundays’, meaning a long time. ‘A young heller’ for a mischevious child and ‘Weskit’ for waistcoat.

Under ‘Farming words and dialects’ Sylvia also reminded me of ‘Clinting’ for hammering over a long nail and ‘Faggot’ for a bundle of sticks for firewood. Also ‘Plush a hedge’ (or plesh) for cutting a hedge growth half way through, then laying the top growth lengthways parallel to the hedgerow. ‘Shooting’ for guttering on a building and ‘Trow’ for an animal feeding trough.

Also familiar were some ‘Weather Sayings’, such as ‘Mackerel sky—never long wet, never long dry’ as a white streaked sky with clouds means very changeable weather. Another saying may be useful ‘If it is fine on 21 June it will be set fair until 21 September’ and of course ‘When cows lie down it will rain’.

I recall from my early days reference to someone being ‘Sawney’ meaning having slow, drawling speech and possibly slow of thought. Also ‘Leery’ as being hungry, empty and ‘Na’r a’ for never a. Then ‘Sprack’ or ‘Spreck’ for well, active and ‘Withwind’ for bindweed, also ‘Stout’ or ‘Stoat’ for a cowfly. These last five are recorded by William Barnes, too. He has also recorded ‘Hangen’ for sloping ground, ‘Hazzle’ for hazel, ‘Heal’ for hide or cover, ‘Het’ for heat or hit, ‘Kecks’ for cowparsley stem, ‘Knap’ for hillock or knob, ‘Leaene’ for lane, ‘Mammet’ for scarecrow, ‘Nesh’ for soft, ‘Nitch’ for large faggot of wood, ‘Par’ for shut up or close, ‘Ratch’ for stretch, ‘Scram’ for distorted, ‘Send’ for shower, ‘Wont’ is a mole, and ‘Wops’ for wasp.

Sylvia Creed also quoted from a charter granted to Whitchurch in 1240 which includes an early name for Marshwood as ‘Capella de Mersewode’.

Bridport History Society does not meet in July and August, but we hope to see you all in September.

Cecil Amor, Hon President, Bridport History Society.

On the Box

I remember our first telly with a rosy warm nostalgic glow. Warm because the thing glowed so hot after half an hour, we could have toasted our tea cakes on it. It was a majestic big brown box with a shuttered wood door standing in the corner of the sitting room. The box might have been large but the picture was small, fuzzy, grey and intermittent – mostly when my father moved the indoor aerial two inches to the right to avoid snagging his pipe. My sister and I used to stare at this box in eager anticipation and, if we had been particularly good, my mother might actually turn it on! Yes, it was tea and Bovril sandwiches with either ‘Andy Pandy’ or ‘The Woodentops’.

Some of you may know (older ones might even remember) that these were the olden golden days of black and white telly when we were entertained by Michael Miles with ‘Take Your Pick’. Sunday nights were incomplete without the ‘London Paladium’ and the world stopped (or at least it did in our house) when BBC presenters introduced the evening’s nine o’clock news in their dinner jackets. It was only later that we all grew up and Bill and Ben got done for possession of Weed and ‘Muffin the Mule’ got you ten years in solitary…

A major difference between now and then was having to be ‘in’ at a particular time of the day so you could watch your favourite bit of telly. I’ve already mentioned the 9 o’clock news when my father would clear his throat, turn down the lights and mentally prepare himself for half an hour of serious telly delivered in a semi-religious monotone, but the important thing was we had to be home and dinner finished and cleared away in order to watch it. It was a form of time control, of ritual restraint, of old-fashioned order… A genuine Saturday could never fully exist without ‘Doctor Who’ (5.15pm) or ‘Dixon of Dock Green’ (6.30pm). When ‘The Forsyte Saga’ (every Sunday at 7.25pm) was in full bloom, pubs closed early, streets were deserted and the church had to change the time of Evensong when Eric Porter clashed with Nyree Dawn Porter.

But this was all before TV became a waterfall of streamed services. Nowadays, you don’t need to be home at exactly one minute to nine to watch the news, because you can watch it at 9.04, 9.09 or catch it up at 9.28. It’ll be mostly the same but it might be a little later, that’s all. And you really don’t have to cancel dinner and put off your holiday plans for ‘Game Of Thrones’. You can catch up all of the episodes and binge-watch the whole lot by yourself on a succession of 36 days and nights with only a chest freezer full of frozen pizzas and several gallons of home-made cider for company. You will then emerge heavily constipated with a severe indigestive hangover, but at least you’ll have had the pleasure of being fully entertained! Not only entertained, but swamped, waterlogged and sodden with dragon vomit…

Surely the ITV’s and BBC’s days are out-numbered as we are all willingly submerged in a torrent of digital goo. I think there are now possibly more channels than there are viewers to watch them on some evenings. In addition to Amazon Prime, Sky, BT TV, Virgin Media and Netflix, we’ve got another hundred and seventy-five channels including History, Yesterday, Now and Today. I expect it won’t be too long until we can watch the Future Channel which will preview exactly what to see in Spring 2020. Oh, there already is one? There you go… that’s progress for you. I shall now make plans to avoid certain days in next year’s viewing diary.

Our lives are measured not only by when to watch essential stuff (‘Strictly’ or ‘Killing Eve’) but also by when to avoid some of the other stuff. Here I’m talking particularly about the tackily sleazy ‘Love Island’ which is broadcast nearly every evening so is quite difficult to avoid unless you take up pot holing (no TV underground) or take up evening classes in something artistic like Russian literature or 18th century furniture restoration. And whatever you do, don’t go on holiday to Majorca to escape it because that’s where the wretched series is filmed. Obviously, there are a lot of people in this country who like a bit of jovial gossip plus some occasional leering and inuendo – a bit like the Archers only with less clothes. However, I will admit it’s much more entertaining than watching endless reruns of leadership elections or what-ifs over Brexit negotiations. Perhaps it would be more acceptable if they all wore evening dresses and dinner jackets just like my childhood BBC TV newsreaders. Must keep the standards up…

Junglenomics – Simon Lamb

Author of a new book on our environment, Simon Lamb talks to Fergus Byrne about an alternative way to deal with the economy and our fragile planet.

Before presenting his seven stages of man, Shakespeare wrote: ‘All the world’s a stage and all men and women merely players’. It’s an observation that might describe how we live within the world around us today. But there’s a problem with some of the players. We may well be actors on a grand stage, cogs in the wheel of our planet’s journey or bit players in the game of life on earth, but – in the ecosystem that is our world – we’ve been playing dirty. So dirty, in fact, that we’re ruining the game.

But that doesn’t mean the game’s over. After decades of highlighting the damage our species has been doing to our environment the debate is no longer about whether we are having a detrimental effect on our planet – at last the debate is about how to deal with it. Nonetheless, like all debate, there are different points of view, and whilst some believe we need a harsh form of environmental austerity, others think that technology will come to our aid. In a new book just published, West Dorset’s Simon Lamb sets out the fundamentals of his vision of how we might develop solutions to some of the major problems facing our planet’s future.

Junglenomics. Nature’s solutions to the world environment crisis: a new paradigm for the 21st century and beyond, takes a holistic approach to our world, placing us as key players in a huge ecosystem. Using this fundamental premise, along with the observation that market economies are no different to natural ecosystems, Simon has focused on looking deep into Nature for guidance on dealing with the pollution, degradation and destruction of our natural environment.

With great patience and obviously exhaustive research, he has traced the origins and growth of our environmental problems from the birth of farming to the development of modern money-based economies. He argues firstly that, just like species in ecosystems, we humans are genetically programmed to seek out new resources, what he calls ‘resource hunger’. And secondly, that we inhabit a worldwide ‘economic ecosystem’ in which people act out roles that are the exact equivalent to species in natural ecosystems. The only real difference is that ours is a ‘virtual’ ecosystem, where rather than needing to evolve physically to occupy a new role, we are ‘avatars’ who can step in and out of roles as the opportunity arises. In the economic world, technology is the equivalent to evolution, and the roles of money, innovation and markets have combined to evolve a vast array of niches where none previously existed; for example in electronics, energy and financial services.

The great difficulty is that, whereas nature moves slowly and normally finds ways to deal with the mess that different organisms leave behind, we currently don’t. Think dung beetles cleaning up waste to their own advantage, or the respiratory coalition between plants and animals that ensures each provides the other with oxygen on the one hand and nitrogen on the other. Put us into the picture – with our ability to speed up the process of utilising resources using technology – and the resultant waste grows so fast that we haven’t found a way to clean up before finding new resources to exploit. Like children rushing to open the next Christmas present before appreciating the one they have in their hand, the march of technology allows us to exploit the world around us faster and faster, with little notice of what we have just done.

It was after reading about Thor Heyerdahl crossing the Atlantic in RA ll in 1969 and the floating mass of waste that he came across, that Simon began worrying about what was happening to our planet. He began to read various stories of environmental issues and was especially struck by the damage done to rainforests. ‘I came to realise that behind it all is a drive to colonise new resources’ he explained. ‘Not just your everyday resources but new resources.’ He began to get more and more agitated by what was going on in the world. ‘Why are we, the most intelligent species in the world, steadily, inexorably destroying the thing that we depend on?’ he asks. ‘There is something deeper going on besides economics, there is something much deeper behind it all. Because it is suicidal. Does it happen in nature? Yes it does happen in nature. You do get bursts of invasion by species. They always die back because other characteristics in the ecosystems tend to damp them down. We have a balanced ecosystem with checks and balances in it. Once you see that – working out the chain that actually developed from when we started as hunter gatherers – you can see that we’re living in an economic ecosystem exactly like natural ecosystems. The thing that’s different about it is the speed that it moves at and the fact that we’ve unified resources which might otherwise be nutrients; magnesium, carbon, whatever it is that the said species need to live off. We’ve unified all those into one resource called money. And that translates into anything – it could be a tree, a flower pot or it could be a house or whatever, it is the universal resource.’

Junglenomics uses the principal of ‘symbiosis’ or ‘beneficial mutual dependence’ to suggest a more focused approach to how we deal with our ever growing pile of detritus. This includes nurturing and fast-tracking “good” technology and environmentally benign markets to control or eliminate “bad” ones; by establishing economic symbiosis to clear up behind polluters; by enlisting powerful economic actors in pursuit of “green” profit to conserve and restore vulnerable wilderness; and by re-valuing environments.

‘In nature’ says Simon ‘species co-evolve, so when a creature starts producing waste – and it’s all a very slow process – other creatures come to feed off that. They’re not doing anyone a favour, they’re not doing a service. They actually find that waste profitable. So everything is profitable in nature – that’s why there’s nothing wasted.’ Organisms in nature have evolved in order to colonise the ‘golden opportunities provided by the detritus of others.’

Junglenomics provides shocking statistics and forecasts relating to the chief areas of environmental concern, including pollution in land, sea and air, energy reform, loss of primal wilderness, overdevelopment, biomass decline, and extinctions. But Simon points out that with the necessary incentives and conditions, innovators and entrepreneurs will emerge to seize opportunities. They will be drawn to what he describes as ‘the honeypot of profit’ that could come from performing clean-up services that the present economic ecosystem so badly needs. We, as the species that has tipped the balance, have the ability to create systems to deal with our problems, but waiting for technology to catch up may take too long.

Simon highlights the old adage “Where there’s muck, there’s brass” but cautions that although it’s up to us to copy nature we need to interfere and create an ‘ecosystemic, market-based solution’ to environmental problems. Markets require ‘economic stimulation’ and we need to be far more proactive in promoting ‘viable symbiotic economic partnerships.’ A tree in a rainforest needs to become more valuable alive than dead. ‘While economics makes that tree worth more as a piece of lumber than as a rainforest tree, that is what’s going to happen –because of the resource colonising need that is in our genes.’

Amongst the many options highlighted in Junglenomics is the Polluter Pays Principle (PPP) where polluting businesses pay for their clean-up costs. There has been some effort to implement this initiative. However, Simon points out that the receipts from these levies need to be ring-fenced for use in developing technologies and systems to offset environment problems. Contributions being ‘quietly diverted to non-environmental matters’ by cash-strapped governments make a farce of the value of initiatives like PPP. Pollution penalties become ‘cash cows’ for governments short of revenues. These receipts must be used to address the problems they are contributing to.

Junglenomics also highlights other areas where we can become more efficient such as Carbon Capture Storage (CCS), which Simon believes is an important element in rescuing our planet from climate change. ‘Is the world quite mad?’ he asks in relation to the fact that a helpful system such as this is right under our noses and not being properly utilised. CCS takes carbon at source, pressurises it into a liquid and sends it back deep underground to be locked away under impermeable layers of rock. He quotes Tim Bertels, Shell’s Global CCS portfolio manager as saying: “You don’t need to divest in fossil fuels, you need to decarbonise them.” And Matthew Billson, programme director of Energy 2050 at the University of Sheffield, who calls CCS “the Cinderella of low carbon energy technology”.

One very clear point in Junglenomics is the realistic support of businesses to carry on developing and maintaining economies. It’s abundantly clear that energy austerity simply won’t happen. The book points out that legislation against powerful industries and ‘punitive taxation’, without encouragement and incentive to evolve improved sustainability, will only encourage them to invest in public relations spiel. This is one of the many elephants in the room. The use of PR firms and political influence, rather than finding remedies, will always be more palatable than admitting wrongdoing – so the carrot needs to be much bigger than the stick.

Junglenomics doesn’t attempt to offer an exhaustive or ‘sniffy’ tome of academic detail on environmental issues, nor does it pretend to deal only with new ideas. Simon Lamb has taken what nature does best and used it to identify a way ahead for our planet. He has created a focus or ‘blueprint’ to use as a model to work with. ‘We need to carry people forward with a message at this point’ says Simon. He believes we need to settle what, in comparison, are ‘petty’ problems elsewhere, in another arena. ‘This is too big and important’ he says, ‘I cannot see how people can create policies, create a plan that David Attenborough called for at Davos, if you don’t understand the fundamentals. Until you understand the anthropological reasons, I don’t think you can address it.’ From an economic point of view he says, ‘It isn’t not having growth that’s the problem, because you can have green growth. Make that tree worth more standing, make that tiger worth more alive. Not just to people – but to powerful people.’

Simon believes that the ebbs and flows of products and services through markets and the fine balances struck between competing, parasitic and cooperative elements in business, along with the identical nature of underlying motivations, shows that economies are subject to entirely natural laws and protocols. Junglenomics not only puts forward a blueprint for governments around the world to follow, it also investigates real solutions to individual issues. However, Simon is not so naive as to be unaware of how ambitious his suggestions are. The changes he outlines would require ‘understanding, acceptance, consent and action at the highest levels’ if they were to move leaders of the world communities toward a ‘broad unity of purpose’.

So the question is why should they listen now? Because Junglenomics not only eschews a political agenda, it also doesn’t advocate unattainable economic restraints. It is neither anti-capital nor anti-growth, and though not afraid to implement levies where necessary and change habits that are unhealthy, it is utilising a tried and tested model supplied by nature to deal with a real problem.

As we go to press the Government has announced its commitment to net zero greenhouse gases by 2050. Although that’s a step in the right direction, it is no reason to relax. ‘Setting a legal deadline for net zero emissions by 2050 is a legacy Mrs May can be proud of’ says Simon. ‘But important though this is, carbon emissions are but one part of the catastrophe we are inflicting on the environment. We need equally bold moves on conservation, recycling and pollution control to complete the picture. Britain needs to become the world leader in all these things and to devote maximum energy to their adoption worldwide. Only then can we look forward to the future with renewed confidence.”

Shakespeare finishes his poem in, As you Like It, by describing the final stage of man’s “strange eventful history” as “second childishness and mere oblivion, Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.” If we are just players on this grand stage and “mere oblivion” awaits us all as individuals, that’s fine. But we don’t have to subject the planet and our grandchildren to the same fate.

For more information or to order a copy of Junglenomics visit www.junglenomics.com

Waffle – more than just talk

Margery Hookings is intrigued after receiving a phone call about an innovative project aimed at combating loneliness. She goes to East Devon to find out more.

The wonderful sweet smell of waffles is the first thing your senses pick up when you go through the door into one of Axminster’s newest cafes.

But this is more than just a café. It’s Waffle, a not-for-profit community enterprise that aims to get people talking. Together. Its existence was brought to my attention by a friend who used to live in my village before he and his wife moved to Axminster.

‘You must come down and take a look for yourself,’ he said on the phone. ‘I think you’ll like it. It’s quite remarkable.’ That was something of an understatement. The café itself is cool and inviting. And buzzing with people of all ages.

Incredibly, the idea for Waffle came to Matt Smith, 29, one of the café’s three directors, in a dream. But more of that later.

When I arrive, Tim Whiteway, 28, another director, is hard at work in the kitchen, creating the waffle dough. This is where the lovely smell is coming from. It’s intoxicating. The Liege waffles are made to a special recipe from the grandmother of fellow director, Sophie McLachlan, 31. She says: ‘My nan, who is from Belgium, was stopped by the Nazis when she was a little girl, but due to her having a certificate that she was christened, they let her go. They went into hiding and also hid Jews in their attic. My nan would always eat waffles with her family and when she moved to England it was a family tradition. I have always loved waffles, so my nan passed to me her secret recipe, which I’ve changed around to make even better. It’s great to be able to look at the public loving our waffles and enjoy a taste of Belgium.’

In the main street where the RSPCA charity shop used to be, Waffle is in the heart of community. Its aim is to tackle loneliness, isolation and exclusion by encouraging interaction across the community. Between 30 and 40 people have been involved in getting the café to where it is now. There is a team of seven staff, including the directors, who are all paid the real living wage, and around 12 volunteers.

One hundred per cent of Waffle’s profits are given away—this year to the Axminster Christmas illuminations fund (Light Up Axminster). Explains Matt: ‘Through the power of Waffle, we wanted to bring people closer together and to help the community. Our vision is to create and serve the highest quality, fresh Liege waffles, along with local and freshly-made coffee, cakes and juices. We also want to use Waffle as a community hub to forge unlikely friendships across the community of Axminster and help to combat loneliness and isolation through the intentional and creative use of waffle.’

All three directors are friends and grew up locally. Their connection is the Church. Says Matt: ‘Tim grew up here, he’s Axminster born and bred. He was always known at Axe Valley School as Tuck Shop Tim, exploiting the Jamie Oliver years. He did really well with it. He’s an entrepreneur, with a brilliant business mind. Sophie runs a charity in Kenya. She’s from Charmouth and went to Woodroffe. She’s always wanted to run something in the evening—but not a pub—that sells desserts. She had a Belgian nan who had this fabulous waffle recipe.’

Matt, who went to Colyton School, moved to Seaton at the age of nine. For six years, he worked in marketing for Lyme Bay Winery. ‘My passion is community,’ he says. ‘I very much enjoy the relationship between community and communication. For a long time, I had been looking at ways of bringing the community together. Cafes are, often inadvertently, prime spaces for social action and interaction. I wanted to see that done intentionally.’

So what about that dream?

‘I literally had a dream about starting a café. In my dream, it was Honiton, not Axminster. But I spoke to Tim and Sophie about it. And now here we are.’

The five-year lease on the shop began in November last year, with Waffle opening its doors in mid-April. The directors had conversations with other cafes in the town beforehand because they did not want to undercut them or compete.

‘We put everything we could into it,’ says Matt, who now lives with his young family above the café. ‘We didn’t have any loans and started as a community project. We did crowdfunding as well as applying for grants. We spoke to Axe Valley School and the police to see what was needed, looking at ways we could serve the community by taking our lead from the community.

‘Loneliness and isolation is a big thing for us. It’s a massive subject and we realised it exists in various forms in Axminster, in people of all ages. It’s a hugely chimeric thing and it’s hard to put your finger on it. We didn’t know exactly what to do but we didn’t want to do nothing. There is someone here at Waffle who is always available to talk. We have done training sessions with a counsellor on listening, so we’re equipped to fill the gap between unskilled listener and counsellor.’

Matt is a member of ‘The Fold’ Church in Axminster, while Tim belongs to Seaton Baptist Church and Sophie to Crewkerne Community Church. Says Matt: ‘Our motivation for Waffle has come through our faith. We have a love of people which we really wanted to demonstrate but we wanted to be very deliberate about Waffle not being a Christian “thing”. The important thing about Waffle for us is that it is a place where people can come with all sorts of views and be listened to. There is a lot of healing just from being listened to. The demand is there. It’s a place to chill and be unhurried.’

Waffle is open from 2pm until 10pm, Tuesday to Saturday. For more information, visit waffle.org.uk

UpFront 07/19

Although developed by the Japanese in the 1980s’ Forest Bathing’ has been in the news again recently. Known as ‘shinrin-yoku’ which means ‘taking in the forest atmosphere’ it is said that the practice of spending quiet time tramping through forest or woodland reduces stress and brings a sense of wellbeing. It is also said to help lower blood pressure and even help concentration and memory. I spent a lot of time with publisher and poet, the late Felix Dennis, while he was developing his plan to grow the largest broadleaf forest in England. When the weather was good, we occasionally walked across his garden to one of his writing dens. We would stop at different trees, and he would gently check the state of branches, leaves or buds, and in his signature gruff and loud voice, he would ask the tree how it was doing. In the end, despite his obsession with writing as much poetry as he could before he died, he left his business and his money to a charity devoted to growing native broadleaf trees. He firmly believed in the social and health benefits of trees for both the planet and its inhabitants and hoped to eventually plant a contiguous forest on land near his home in Stratford-upon-Avon. He dreamed of creating a place of tranquillity and natural beauty. I was with him when he planted his millionth tree, and to date, the organisation that inherited his money has created over 3,000 acres of new woodland. I have little doubt that a walk in the woods has health benefits, even the National Trust offers a ‘Beginner’s Guide to Forest Bathing’ on its website and promotes the belief that ‘improving a person’s connection with nature’ can lead to ‘significant increases in their wellbeing’. While trees have often been used to symbolise strength, wisdom and eternal life, the idea of a community of them offering peace and tranquillity is warming. So when much was made recently about the fact that the tree which President Emmanuel Macron gifted to the current US President died after a spell in a US quarantine facility, I was as amused as the many others who saw it as a sign of the deep chasm between symbols and reality. But it didn’t stop me from seeing the value of the mental health benefits of a walk in the woods. President Macron is reported to be sending a replacement for the dead oak. Perhaps instead of sending just a replacement, I wonder if the world could benefit if he sent over a small forest for the White House lawn so the current resident could take in the forest atmosphere and chill out now and then.

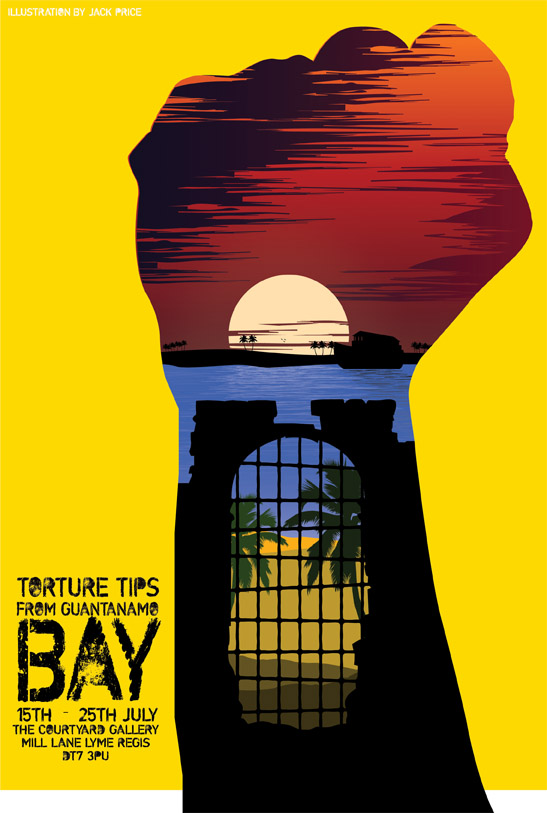

Torture Tips from Guantánamo Bay

Deciding what the world may see of Guantánamo Bay is an uncertain process. Over the years, representing the detainees with my colleagues at the charity Reprieve, I have indulged in a little light entertainment testing the limits of the censors’ paranoia. For example, Jack and the Bean Stalk got banned—perhaps because detainees might escape, using a magic bean. Sometimes the censors are more depressingly predictable: with art that portrays torture.

Eighty of my clients are free, but there are two fine artists among the forty men who remain there, seventeen years after it was opened. Under President Donald Trump some of their pictures have no more chance of release than they do. When Ahmed Rabbani portrayed himself being subjected to strappado—an age-old torture once employed by the Spanish Inquisition – the censors’ stamp came down hard. Admitting your international war crimes is, of course, a threat to national security. During my visits to the prison, I have seen Ahmed’s torture pictures, as well as Khalid Qassim’s, and I wish you could too. You never will. However, the censors did allow my detailed description of them out. For example, “a dark haired man is in a twenty-foot pit, a square of neon light above him … his wrists are shackled to a bar … he is forever on tiptoes. And there he stays for days on end.”

Curated by student Ruby Copplestone, Torture Tips from Guantánamo Bay brings professionals from Axminster to Australia together with artists from Woodroffe School to reinterpret Ahmed’s and Khalid’s art—liberate it, if you will—so visitors to the Town Mill Courtyard Gallery may see that which is forbidden. Later in the month, the project will link arms with Shire Hall in Dorchester, where Royal Academy artist Bob & Roberta Smith is leading a programme on the Tolpuddle Martyrs.

Some parallels are obvious: the agricultural labourers, demanding fair treatment, were accused of swearing a secret oath to an evil union assemblage; they were rendered 10,000 miles to Australia for their sins. Almost two centuries later, Ahmed and Khalid were accused of swearing an oath to another hated group (al Qaida), of which they were likewise innocent. They were rendered in turn round the globe from Karachi to Guantánamo Bay. It is here that the parallel ends: after two years, public outrage prompted the government to pardon the Tolpuddle Six. Ahmed and Khalid have never enjoyed even the inequitable Shire Hall trial permitted in 1834, and they remain in their Cuban prison cells after 17 years.

Ruby Copplestone shines a light on their plight. I will be one of several ‘experts’ privileged to give a series of talks during the ten days of Torture Tips from Guantánamo Bay—from July 15-25. I hope you will join us.

July in the garden

I know it can’t be true, it’s merely a coincidence, but having promoted water saving last month it seems to have done nothing but rain ever since. Having had a relatively dry summer, last year, it is easy to forget that, in reality, wet weather in June is pretty standard for the UK. With any luck July will be sunnier, warmer and drier to make up for it.

At least the plentiful rainfall will have saved you a lot of time that might otherwise have been spent watering. The heavy downpours, together with periods of more steady rain, resulted in even my containers remaining reassuringly moist. I normally advocate watering containers, even when other areas of the garden survive with natural rainfall, because light rain and the odd shower are not enough to keep the compost in pots and containers sufficiently wet in the summer.

Having said that, rain does not contain any of the nutrients which plants, growing in finite volumes of compost, require. Therefore maintaining your usual regime of liquid feeding is important. In fact, it may be more vital because heavy rain leaches out many nutrients present in fresh potting compost so replacing the lost nutrients, with supplementary feeding, is a good idea.

Now that we have passed the longest day of the year the rapid early plant growth slows down and early summer flowerers will switch to setting seed instead. Plants that flower in late summer will, thanks to shortening days affecting the ratios of the various growth hormones, change from vegetative growth to the development of mature flowers. These changes are gradual so, as a gardener, you don’t have to plunge into sudden action, intervening in a mad panic, but it does signal a slight shift in the tasks required.

The classic example is shortening the long, whippy, growths on wisteria. Climbing and rambling roses should also be tackled. Proper ‘climbers’ are pruned in the winter months but the nice extension growths, which seem to have shot up out of nowhere, need to be loosely tied in before they lose their flexibility. On the other hand, ‘ramblers’, which have had their single flush of flowers, can be tackled now. You need to prune out the shoots which have finished flowering while keeping the strong, new, shoots which have arisen from near to the base. These shoots will still be soft and flexible, but easily damaged, so tie them in to replace the old shoots that have been removed.

The same change in hormone levels and proportions, responding to day length amongst other things, makes ‘high summer’ the most propitious time to take cuttings of many shrubs and tender perennials. I use the same technique for practically everything in the garden. Generally I take non-flowering shoots, thick enough to withstand pushing into loose compost, and trim them up so that they are roughly finger length. Remove all foliage save a couple of leaves at the shoot tip. If the specimen has relatively large, soft, leaves then, using a sharp knife, reduce the size of the leaves at the tip. Trim up the cutting so that the base is cleanly cut, under the lowest leaf joint, with no ‘spare’ stem, or damaged material, below this last joint. It’s important to use a very sharp knife so that it cleanly slices, rather than crushes, the plant material. Clean cuts and undamaged cells are key to maximising the likelihood of the cutting rooting rather than rotting.

Insert the cuttings into moist, ‘open’, compost. ‘Open’ refers to a compost which has a high proportion of drainage material incorporated to increase the size of the air pockets within its structure. Air is just as important as water for healthy root growth so, when the name of the game is to get the cutting to produce roots, it is vital for a cuttings compost. I get the best results from using a multi-purpose compost with the addition of at least 50% grit / perlite. Once mixed this compost would have been lightly firmed into the pot, not rammed hard, which again helps to ensure that there is still plenty of air left in it.

The cuttings are inserted around the outside of the pot, where gas exchange with the atmosphere is at its greatest, and water in well with a fine rose. To maintain a humid atmosphere place a polythene bag over the whole ensemble and tie at the top. A length of cane pushed into the centre of the pot keeps the bag off the cuttings and gives you something to tie against. Tender perennials should root readily, under their own steam, but hormone rooting powder may assist in slower rooting specimens and can guard against rotting off as it also contains a fungicide. Place somewhere protected, such as a light windowsill, but not somewhere where they will roast in the noonday sun.

General maintenance carries on with, perhaps, even more to keep on top of. Lots of dead-heading, watering and feeding of plants in containers. Regular grass mowing (I’m very lax at this!) plus weed and pest removal. Keeping on top of the ‘refereeing’ side of horticulture is the main aim at this point. Any plant which is being too boisterous, threatening to swamp its border mates, either needs to be cut back, early flowering herbaceous perennials generally bounce back from this, or propped up, deploying hazel hurdles / emergency pea-sticking, to keep them within bounds.

Gardening is, after all, the gentle art of manipulating nature. These days it is possible to be a lot more relaxed about the degree of wildness permitted within even a relatively formal garden. According to the ‘ancient rules of garden making’; any area of garden immediately next to the house should be regimented, controlled, and largely artificial—epitomised by the ‘rose garden with clipped box edging’—a style which has largely disappeared these days.

The further from the house you ventured, the more ‘wild’ the garden was allowed to become. Domestic gardens are, by their very nature, smaller, less grand, and the trend towards wildlife gardening means that the entire garden can have the same planting style. If anything this blurred line demands your skilful intervention more than ever. Your input is all that is preventing ‘nature perfected’ from descending into ‘nature untamed’. Untamed wilderness is not a garden!