In 1882, legislation was started to enable Somerset County Council to acquire land for smallholdings. But it was not until the passing of the Smallholdings and Allotments Act of 1908 that Somerset began to create a smallholdings estate. Margery Hookings’ grandparents were tenants of neighbouring farms in Donyatt. The council bought the village in 1918 for £100,000.

I was born and brought up at Park Farm, Donyatt, in the house where my father was born in 1925.

It was part of an estate of smallholdings set up by Somerset County Council for men who had served honourably in the First World War.

My paternal grandfather, Arthur Hull, was among the first Donyatt tenants. He had enlisted with the Australian Imperial Force at Sydney Showground in 1914, just a few years after leaving England with his friend, Ernest Hoare for a new life Down Under. Arthur fought at Gallipoli and Delville Wood, France, and never returned to Australia. He came back to Blighty, wounded, on a hospital ship, just as Armistice was declared.

Ernest never returned. He died in action in 1916 and is buried at Courcellette Cemetery.

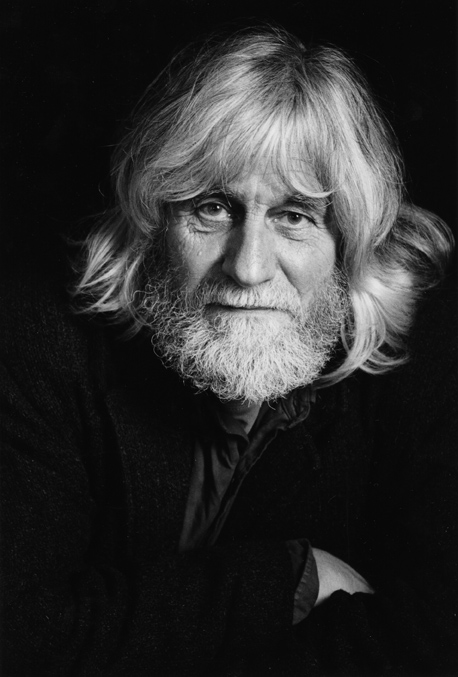

My maternal grandfather, William Percy Withers, was the tenant of Coldharbour Farm, the next one on from Park. Percy, as he was known, was a veteran of The Somme where he served with the North Somerset Yeomanry. A keen observer of everyday life, he kept a record of those terrible times in his journals, which are astonishing in the matter-of-fact way he deals with death and destruction. What comes through in his memoirs, and the poems he wrote subsequently, is the extraordinary sense of camaraderie in the face of such adversity.

In 1918, Somerset County Council bought the Donyatt Estate from Mr R T Combe of Earnshill, for £100,000. This family had owned the land and had been the Lords of the Manor since 1755. Additionally, further land was bought from the Dowlish Manor Estate, owned by the Speke family, and the land was carved up into parcels of between one to fifty acres. The number of agricultural labourers dropped considerably.

My mother has a newspaper cutting from 8 May 1920. We don’t know which paper it was from or the name of the correspondent, but, under the heading ‘Village bought for ex-soldiers’, the following picture emerges.

“What do you think of Somerset?” asked mine host at Ilminster.

“It looks a county fit for heroes to live in,” I said, looking across a golden valley where the cattle waded knee-deep in buttercups.

“Aye, and we’re making it one,” he replied. “Do you see the church tower among the trees? That’s Donyatt Village: Church, School, Inn, houses and shops complete, with the surrounding estate, it has been bought outright for ex-servicemen who wish to settle on the land.” As this sounded more like a politician’s promise, I decided to investigate.

Donyatt was only a mile away through the fields and here I found a score or two of sturdy stone houses, some with bonnets of thatch pulled low on their brows and diamond lattices winking drowsily in the sun, all shaded under the great elms.

At the estate office in the village I met Colonel Locke Blake, a member of the Somerset Land Settlement Committee, who assured me not only was the story of purchase of the village was correct, but also that the scheme of establishing ex-soldiers on the land was in operation.

“Somerset is the leading county in this work,” he said. “It has acquired 11,459 acres. On this estate we have purchased 2,230 acres and have divided it into smallholdings. We have taken over the whole village, which lies at the centre of our property. With the exception of the rectory, the rectory cottages and the almshouses, everything is ours. The living (responsibility to elect the Parson) of the church belongs to us. The village school, the post office, a fully licensed inn, a baker and provision dealer’s shop, a smithy, the businesses of wheelwright, cobbler and ropemakers, potteries, grist mills and a quarry are included in our purchase.

“The school will be resold to the county education authorities, and instead of being a church school it will be a council school. The inn will be let to the Western Counties Public House Trust and the Bakery, Blacksmiths and Wheelwrights’ shops will be given to ex-servicemen. We hope in time that the whole community will consist of such. All available cottages with a small piece of land have been allocated to demobilised soldiers, who will assist in running the estate. The rope-workers will be allowed to stay, but the potteries may not continue. Our quarry ought to prove a valuable asset.

“The colony is split up into some eighty agricultural holdings varying from one to fifty acres, and so far we have settled about one hundred ex-servicemen either as smallholders or estate workers. We have a market town and railway station at Ilminster, only a mile away. The River Isle runs through the centre of our property, and generally speaking the land is well watered for cattle, while homesteads have ample resources for drinking purposes. The majority of the land is mostly what we call two-horse land. A drawback is that a good deal of the arable land is hilly, but it can be grassed down. Our estate is exceptionally well wooded and the timber is very valuable. A lot of it has been ‘thrown’ and will be converted into gates and posts. At the estate office we are setting up carpenter and painter’s shops, sawing and drying sheds and a timber yard. All the holdings have been let an economic rent and we mean to keep strict supervision over our people to ensure they farm the land to the best advantage. There is bound to be a loss on the scheme at first, owing to the enormous cost of building and repairs, but in time the colony ought to be a paying concern.”

Cupid has been busy down Donyatt way. Since the estate was opened between ten and twelve of the newcomers have married and, as the housing problem will soon disappear, the parson will look forward to a lively season.

In the years that followed, there was much activity on the estate, through lean periods as well as the golden times. Sadly, in recent years the county council has sold off many of the farms.

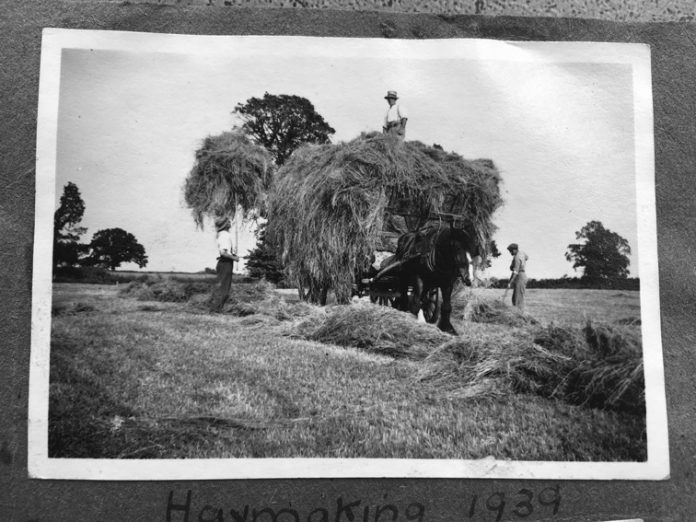

• I am indebted to my mother, Pamela Hull, for the information she has compiled over the years, some of which appeared in The Story of Donyatt, a book brought out in 2000 to celebrate the millennium, and for the family photographs. The pictures of present-day Donyatt were taken by my brother, Andrew Hull. Destination Unknown, the memoirs of Percy Withers, was published in 2015 through FeedARead.com