Talking on BBC’s Radio 4 recently, wildlife photographer, Paul Williams, who suffered debilitating mental health problems after a career in the army and the police force, talked about his experience looking for help through the NHS. Despite receiving therapy assistance through his employers after a traumatic incident as a police officer, he knew he needed continued treatment to help him deal with what had been diagnosed as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

After an initial assessment and the knowledge that at last his problems were being dealt with, he had to wait a further seven to eight weeks before his follow up appointment. This gap in the system was long enough for him to make a ‘serious attempt’ on his life. ‘Expectations are raised’ he explained. So that if a follow-up appointment is cancelled or even delayed ‘your hopes are dashed and you are left in almost a worse position.’

David Clarke, NHS England’s Clinical Director, talking on the same programme, pointed out that although treatment gaps are far too long; this is an advance from ten years ago. Then the average time it took for an initial appointment was closer to 18 months. He said the NHS hopes to recruit and train another 4,000 psychological therapists by 2024.

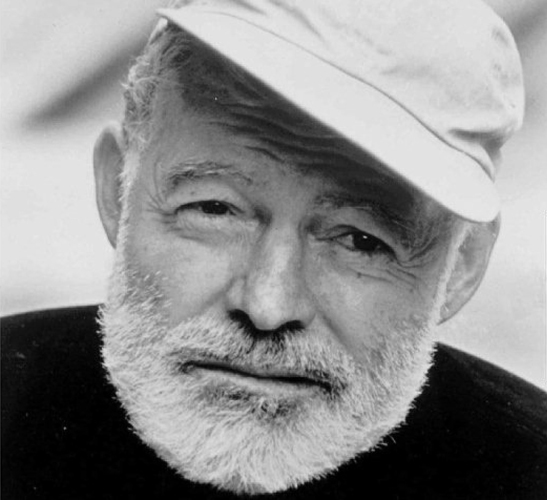

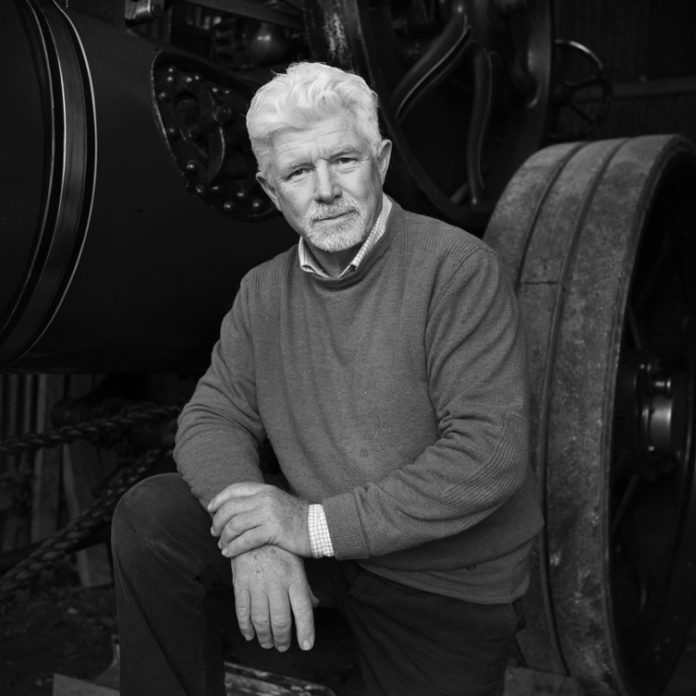

Paul Williams’ journey started with a sixteen-year career in the military. Much of that time was spent as an army physical training instructor. After leaving the military he embarked on a completely different career direction and gained a First Class honours degree in Clinical Mental Health nursing, working as a senior mental health specialist in the NHS. However, when he turned 40 he decided to join the police force and his PTSD developed after he had defended four people against a mentally ill, samurai sword-wielding woman at Bournemouth police station. Following this traumatic event, he became acutely unwell and attempted suicide three times before experiencing a significant breakthrough with a new psychotherapy treatment.

Today, thanks to a combination of advances in treatment and his own determination—partly cultivated from strength of will and discipline developed through his military training – he has been able to move beyond his illness and is enjoying a new career as a landscape photographer.

Already an amateur photographer, Paul picked up his camera again to give him an incentive to get out. Recounting his experience in a new book Wildlife Photography – saving my life one frame at a time, Paul explains the background to his illness and the journey he took to build self-esteem and purpose in his life again. He talks of how wandering through often deserted country paths and fields near his home in Dorset became a blueprint that continues to shape his life. He remembers the joy of discovering hares and a den of foxes living nearby and explained how days spent alone watching wildlife became his quality time; extended moments of meditation in the peaceful surrounds of nature. He practised the Mindfulness discipline of ‘being in the moment without intrusion from thoughts about the past or the future.’

Today, although still scarred by the struggle since his illness began in 2010, Paul looks back on what has happened as a chapter in the book of his life. Wildlife Photography – saving my life one frame at a time is described by Chris Packham as ‘a brutally honest visual journey … uplifting and beautiful’ and Paul’s photographs have won many awards. He looks to the future from a platform of being glad to have survived—and to be alive. He still needs to take time out from human contact for days at a time but for those of us that enjoy his photographs, the results are a benefit that we can all appreciate.

Wildlife Photography – saving my life one frame at a time is published by Hubble & Hattie, an imprint of Veloce Publishing Ltd,

RRP: £29.99.