‘My father’s family had a business at Beckington, near Frome, where they were carpenters/joiners and wheelwrights. After he’d left Frome Grammar School, Father came to Salwayash to stay with his uncle who ran Lower Kershay Farm, which is where he met Mother. At that time Father’s passion for sheep was inspired by neighbouring farmer Percy Warren who kept Dorset Horns. The business at Beckington has been going for generations; Father’s mother was a cheesemaker and farmed in her own right, as were his aunts.

There are two trades in our family: carpenters/wheelwrights/undertakers, which often went hand in hand, and farming. Father’s uncle, who he worked with, was actually born here in our house in Litton Cheney, where his father rented land locally for dairying. And I’ve got an older brother, who followed in Father’s footsteps and went shepherding.

As soon as I was able to carry half a bale of hay I had to go and help Father feed sheep. All his life, the topic of conversation with him was either sheep, heavy horses or farming, in that order. At 13 I was driving tractors, haymaking and harvesting, and helping with sheep work. Father’s work took him all round Dorset, and beyond. He worked for Charlie Borough’s at Halse in Somerset, then for Bill Hooper at Winfrith Newburgh, with Pedigree Dorset Downs. He went to Sussex looking after Kent Romney ewes, then to Rex Loveless’s at Piddlehinton with Dorset Downs again, then to Kingston Maurward to work with the college Dorset Horn flock, until they were sold. That was an old flock, a good one, and when Father was showing them he was giving Fooks’s at Powerstock, famous Dorset Horn breeders, a run for their money and occasionally beating them. He was a familiar sight at agricultural shows and markets, probably known to most Dorset farmers at the time in his flat cap, collar and tie, britches and highly polished brown leather gaiters. He had met members of the Royal Family, including HRH the Queen, the Chairman of Youngs Brewery and the Colonel of the Dorset Yeomanry, all of whom he advised about sheep, and would generally listen carefully to what you had to say about a farming matter before politely telling you how you were wrong. In 1982 after being made redundant from Kingston Maurward, he had the chance to rent a bit of ground in Litton Cheney, so we moved back here and he started his own small flock of Dorset Downs.

I went in the other family trade direction and have been a carpenter joiner all my life, and we do some wheelwrighting. From a young age I wanted to be a carpenter. With a piece of wood, a hammer and some nails, I was happy. After I left school I got a job in Dorchester with an old building firm called CE Slade’s, based down in Millers Close. That was in the days when there were some decent building firms in Dorchester, like Cake’s, Ricardo’s, Angell’s, all very good builders with their own joinery shops. I started in 1970 with Slade’s and soon got into the joinery side of it. I did my apprenticeship there, stayed on a few years, and left in 1978. I’d got married in ’77, like Father to a young lady from Salwayash, Carol, and then went to work for CG Fry’s down the road here in Litton Cheney. I was foreman joiner for them for about 8 years, then left and started on my own in 1986.

Father could always remember his father making wheels, and his brother who was older was involved, but basically the war killed the trade. That was because there were so many rubber-tyred wheels left over from the military which could be reused, tractors were becoming much more common, and when the wooden wheels on the old wagons got shaky they didn’t get replaced. I got interested in making wheels probably 40-odd years ago, and today we both repair old wheels and make new ones. There are still enough old farm wagons in preservation, horse-drawn traps, hand carts, trolleys, etc to provide us with an interesting sideline. To make a new wheel, you start by turning out the hub on the lathe, and that’s always English elm. Then you set out the spokes, always an even number, and fit the iron stock hoops to the hub and drive them on tight. Having morticed the hub for the spokes, you then make them out of English oak, shape them, and fit them by driving them really tight into the hub mortices. There’s never any glue involved. Next job is to cut the felloes (pronounced fellies) out, always English ash. These are the curved sections of the wheel rim, each one joined to the next one with a dowel. The different timber species are used for good reason; the elm is tough and stringy, resistant to splitting even though much of the hub has been removed to take the spokes. Oak is strong, to resist the impact of the weight on the wheel riding over bumps, all of which is on one spoke as it reaches the lowest point of the rotation; and ash is springy, to absorb the weight as the wheel turns. Each of the spokes is cut to length with a “tang” or round tenon on the end, and fitted to holes drilled into the felloes, two to a felloe. There has to be a small gap between the felloes, and in the length of the spokes, so that when the hot bond, or iron tyre, is fitted, the gaps will squeeze up tight as it cools and contracts with enormous force. We do all that ourselves, building a fire round the bond to heat it up before fitting.

On the joinery side, we’ve done some interesting projects. We built a complete horse-drawn hearse once, for Mac Kingman in Weymouth, which he used regularly for many years. There’ve been a few canopies for steam engines, too, and repairs to thrashing machines, including a total rebuild of one, and wooden parts for old farm machines like binders, and years ago a lot of con-rods for the old finger-bar mowers, for Lott and Walne in Dorchester. If it wasn’t for fools like us, and the fools who still have these old machines, it’d all be gone for ever, and it’s part of our heritage; most of the modern machines have simply evolved from these old designs. We’ve also made big Georgian staircases with endless strings, or handrails, which curve in different directions, the last one in Winterborne Keynstone, and spiral staircases too. A helical staircase in a round building was an interesting project once.

Our business is very traditional, and that’s because I’m a bit old fashioned about the way building is done today. Everything has to be done in such a tearing hurry, using products which enable things to be built quickly, as a result of which it often doesn’t last very long. I was taught by some very skilled tradesmen, the sort of people who are hard to find any more, when things were made in tried and tested ways, which for many years had stood the test of time. I still work on those lines, which sometimes leads to arguments with clients and architects, and occasionally I will refuse to price a job if they insist on building something in a way I know won’t last. Traditional ways of building and joinery are done for good reasons, and Chris and I take great pride in what we do. That extends to the tools we use, still sharpening our own saws rather than buying another one with a plastic handle as most carpenters do.

Carol and I have 3 boys, and Christopher decided just before he left school he wanted to follow me in my work, the 6th generation in our family to take up the trade. It was difficult to find a good apprenticeship place for him, so at the time slightly against my better judgement he came to work with me, and has been here ever since. He’s the same as me, in that the work’s got to be right. Nothing leaves the workshop until we’re happy with it, even if we have to spend another day on it.’

Russell Randall

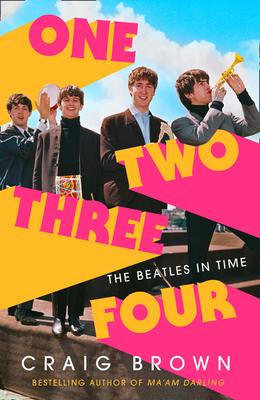

One Two Three Four

On the 50th anniversary of the break-up of The Beatles,

Craig Brown, author of a new book on the band talks to Fergus Byrne

In his 1994 interview for Desert Island Discs, Douglas Adams, who wrote much of the early script for The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy while living in Dorset, related his story of just how obsessed he was with The Beatles while growing up. Standing in a queue to get into his local gym, he and his friends overheard someone say they had just listened to The Beatles most recent song, Hey Jude. ‘We basically held him against the wall and made him hum it to us’ he recalled.

It’s one of many stories that author Craig Brown relates in his new book, One Two Three Four; The Beatles in Time, a fascinating and extensive romp through Beatles stories that, compiled in a loosely biographical format, makes not only easy, but intriguing and entertaining reading.

For example Craig unearths the story of Eric Clague, who drove the car that killed John Lennon’s mother. Though found not to be at fault, Eric was suspended from his job as a policeman and ironically ended up as the postman that delivered fan mail to Paul McCartney’s house. His identity remained a secret until 1998. He hadn’t even known that the lady, tragically killed when she walked out in front of his car, was John Lennon’s mother, until years afterwards. Eric spent the rest of his life haunted by the memory. Up until 1998, he hadn’t even told his wife and children.

Craig Brown also manages to highlight stories like that of the Belgian singing nun, whose song, Dominique, was a huge hit around the time she and The Beatles made their debuts on the same Ed Sullivan show in America. With the arrival of The Beatles, however, the chart career of Sister Luc-Gabrielle ground to a halt. Later she left the convent to pursue a singing career with songs such as Glory be to God for the Golden Pill and Sister Smile is Dead. Along with her later album, I am not a Star in Heaven, they flopped and she became a teacher of handicapped children. Later, pursued by the Belgian authorities for back taxes that she believed the convent, which took most of her royalties, were liable for, she committed suicide with her partner Annie Berchet. Their joint suicide note explained: ‘We are going together to meet God our Father. He alone can save us from this financial disaster.’

With over 600 pages and endless sources, Craig touches on a fascinating selection of tales from The Beatles’ lives. Inevitably there are stories of some of the excesses that helped fuel the band’s notoriety. Recording engineer, Geoff Emerick, who worked with the ‘straight-laced’ producer George Martin on Beatles recordings, recalls when the band were in what he euphemistically describes as a distinctly ‘party mood’. One evening, recording Yellow Submarine, John was determined to try to sound like he was singing underwater. The band had been joined in the studio by Pattie Boyd, Mick Jagger, Brian Jones and Marianne Faithfull when John tried gargling and singing to get the sound he wanted. Only succeeding in choking he insisted on having a tank of water brought in to try to sing underwater. When that didn’t work he finally settled on covering a microphone with a condom and dipping it into a milk bottle full of water. For those, like me, unaware of that story, Yellow Submarine will never sound the same again.

Craig’s eye for a Beatles story came at a young age. He recalls being exactly eleven and a half when he asked his parents to give him The Beatles’ White Album for Christmas. He was totally enthralled, ‘luxuriating in its pure white cover’ and spending hours gazing at the ‘neatly folded’ poster that came with it. He had first heard Lady Madonna earlier that year, on a radio played by some building workers who were fixing the pool, at the catholic prep school he attended near Basingstoke. Immersed in a religiously influenced education at the time, Craig’s memory is that he decided the Virgin Mary must have been an aristocrat. His impressionable young mind had also been influenced by his older brother who had told him that Sgt. Pepper was the “best song ever written”. ‘I remember thinking that was an objective judgement rather than subjective’ he said, ‘like you’d say the Eifel Tower is so many metres high or something.’

However, although not unusual in his interest in music, Craig was in the minority for his age. ‘There were fewer people interested in pop music then in those days’ he said ‘whereas now everyone might have some records, or at least hear it on the radio. In those days it was divided into two, which was those who liked sport and then the tiny minority who liked pop. I suppose I would have known every record in the charts from about the age of nine. If I was on mastermind my specialist subject might be top-twenty hits from about 1967 to 1970.’

Despite suggesting his fascination with pop music might have put him into the minority at the time, interest in The Beatles was not a minority pursuit. Craig was aware of the excitement that surrounded the band during an era that later seemed a very short period of time. ‘They did sort of dominate your thought and there was that amazing excitement about what they’d be doing next’ he said. ‘Now you realise it was only five months maximum between each single coming out. But then it seemed like years, and there was an amazing expectancy. I remember my aunt saying “have you heard the new song”. And that’s from my aunt who wasn’t remotely interested in pop. Everyone would know what the new Beatles record would sound like. It was felt that, with The Beatles there was going to be some kind of extraordinary leap, and usually there was.’

It’s hard for later generations to understand the level of hysteria that surrounded The Beatles. They were four young boys who had to learn about the perils of fame the hard way. And it was during a time of dramatic change in the way young people reacted to the opportunities presented by adult life.

The boys’ introduction to psychedelic drugs, when their drinks were spiked by their dentist, depicts a level of naivety that reminds us of their youth. The book also details the story of how Bob Dylan introduced them and their manager Brian Epstein to cannabis. Craig said that through the process of researching the book, he found himself forgiving some of the excesses the band was often denounced for. ‘They were kids from nowhere’ he explained. ‘They didn’t have training in being the most famous people in the world. So I think I forgive them a lot more now than I would have at the time—not that I condemned them—but people did at the time. They were just people having to find their own way in this extraordinary position they were in.’

Although not intentional, the book depicts a period in Beatles history that was strongly influenced by their manager Brian Epstein, the man who one day walked down the stairs to the Cavern club in Liverpool to see them play. He eventually took his own life and has been the subject of much debate since. ‘I think you could easily argue that if Brian Epstein hadn’t gone down the steps of the Cavern club and then persisted with them that they wouldn’t have been known’ says Craig. ‘He really pushed to get them a record deal when no one wanted them and they didn’t have anyone else who was prepared to do that for them. And they didn’t have any kind of clout or contacts. But I wouldn’t want people to think that I thought Epstein was a kind of Simon Cowell figure.’

Epstein may have been a long way from a Simon Cowell type character but The Beatles were devastated by his early death. It could be argued that without Epstein’s fatherly influence the band might have stayed together longer. ‘They did slightly go off the rails then, but that might have happened anyway’ said Craig. ‘One of the things that intrigued me about Epstein was I had always seen him as this much older person and very straight and establishment. Of course, he was only thirty-three when he died, so he was older than them, but not much older. And though he seemed establishment, he was taking far more drugs than any of them. He was way out of control and miserable. So he was a terribly complex, sad figure and very reliant on them for his feeling of happiness.’

Craig Brown has been careful not to follow the normal biographical system of sticking to a specific timeline in One Two Three Four; The Beatles in Time and the book benefits from that. ‘I wanted to do a book which didn’t go with normal biographical procedure’ he said. ‘So I didn’t want it to begin with something like the birth of George Harrison’s grandfather and then go on til the last day. I didn’t want it to end on April the 10th when they finished.’

As the fiftieth anniversary of the day The Beatles broke up that is indeed a date that his publisher was aware of. Craig should have been out doing radio and television interviews about the book as debate about everything Beatle-related surfaced on the anniversary of their break-up. But like many authors whose books were set for publication this Spring, Craig’s wasn’t available to ship on the day it was published—COVID-19 had made it impossible for the warehouse to get the orders out. Thankfully it is now available to buy, at least online for the moment and it makes a thoroughly enjoyable read.

One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time

by Craig Brown (4th Estate, £20).

Buy it where you can.

May in the Garden

Last month we had just entered the ‘lockdown period’ and it was all a bit of a strange new world. As I write, we are still locked down, for good reason, and my heart really goes out to anyone who doesn’t have a garden to potter around in. In these unsettling times, it’s interesting to note just how many of us are finding solace in good, old-fashioned, practices like gardening and cooking.

In an ironic twist of events, it is the thoroughly modern availability of internet access, home deliveries and online trading which is supporting these traditional activities. Last month I passed on my fears that only buying from remote, online, traders was killing the local, often specialist, small nursery and therefore it’s worth checking with local nurseryman to see if they are still able to supply plants while maintaining social distancing.

May would normally see the grand gardenfest of all things horticulturally excessive; the ‘RHS Chelsea Flower Show’. For the first time in its long history, originally the ‘Great Spring Show’, there is no physical show but the RHS has created a virtual, online, version instead – a pleasant distraction to beat the lockdown blues.

Of more practical help, echoing my plea to carry on supporting nurserymen, they have a section listing those nurseries that would have been exhibiting: rhs.org.uk/supportournurseries. A useful resource but it doesn’t seem to separate out those nurseries that are able to supply plants under the existing social distancing rules from those that can’t. It may be better to use their usual ‘Nursery Finder’, to locate local nurseries, and contact those first.

If you know your budget, and just need a few plants to add to your garden, then a telephone chat with the nursery owner, explaining what sort of garden you have, may yield a box of selected plants, maybe a bit random, which could be left for you to collect without having to enter the nursery at all. Card payments over the phone, or cash in an envelope (remember them?), left in a safe place are still allowed; flexibility is the key in these testing times.

Back to real-world gardening matters; it should now be safe to plant out those tender bedding plants which have been kept protected under glass. Keep some horticultural fleece, or old net curtains, handy just in case overnight temperatures take a tumble. This unnaturally dry, sunny, April may have lulled us into a false sense of security but cloudless daytime skies lead to plummeting temperatures, maybe even a frost, overnight.

If you have tender perennials, such as the woody types of salvia and the indispensable pelargonium, they should have put on a fair amount of growth in the last few months and it’s a good idea to shorten these before planting the parent plants back outside. Try propagating new plants from those cuttings. The hormone levels might make this more tricky now, compared to taking them during high summer, but, with virus-time on your hands, it’s always worth a try.

Shrubs which flowered early in the spring, Forsythia being the most obvious candidate, can be pruned now that their flowers have faded; use the standard ‘one in three’ method. Prune out the oldest wood and flowered stems so that established shrubs never get the chance to become senile but are comprised only of one, two and three-year-old wood which maintains the best balance between vigour, flowering capability and youth. You can roll out this pruning regime, as each shrub finishes flowering because every ornamental shrub benefits from being continuously reinvigorated once it’s filled its allotted space.

Continuing feeding plants that are now in active growth. A gentle, balanced, fertiliser, such as my favourite ‘fish, blood and bone’, is good for beds and borders. A slow-release, pelleted, fertiliser should be added to any plants potted in containers. High maintenance plants, with a greater hunger for nutrients, typically showy plants in bedding schemes, hanging baskets etc., should be watered with a propriety liquid feed according to the instructions on the packet.

I’ve always used ‘Miracle Gro’, the powder form that needs dissolving in a watering can is the most cost-effective, but other brands are available. Most large supermarkets have a gardening aisle so it’s still possible to obtain most gardening sundries while doing your essential shopping.

As things warm up, ponds and water gardens can be spruced up by removing overgrown aquatic plants and re-establishing the balance between the amount of plant cover and the area of open water. Vigorous water plants, irises, reeds, rushes and the like, may need reducing to practically nothing, every now and again, in order to keep them in check. Do not dump these in the wild, where they may become a pest of natural water courses, but chop them up and compost them—or burn them once they’ve dried.

Pests and diseases will be increasing exponentially now that temperatures are rising. Prevention is better than cure, so keep your eyes peeled and squash any pests, of the insect variety before their numbers can reach damaging levels. Lily beetles are well and truly up and about, busy copulating and laying eggs, so pay special attention to any lilies you may have. Lily beetles (they are bright red with black underbellies) can totally wipe out established lilies, Fritillarias are susceptible too, so keeping them in check is essential.

A final mention must go to the lawn. If you are finding that you’ve more time at home than usual then perhaps the lawn could really benefit? Often it’s pretty neglected, not cut regularly enough, never scarified, full of weeds. Lawncare is time-consuming so, if ever there was a time when you could perfect your lawn, now may be that time. Mow it at every opportunity; use a ‘feed and weed’ if you can get hold of some; order ‘lawn repair seed’ to get rid of any bald patches. That’s all assuming you don’t have kids at home—in which case your lawn may be suffering even more than usual!

Wherever you are, whatever kind of gardener you are, stay safe and stay sane. Your garden may prove to be even more of a comfort than usual.

Vegetables in May

May is one of the busiest months in the garden, April is a pretty busy one too (partly why I didn’t have time to write anything for last month’s issue, along with having to completely rethink our business of selling salad and vegetables to restaurants…!). We have now set up a vegetable box scheme delivering door to door to people in and around Lyme, Axminster and Seaton.

Anyway, it is the time of the year when everything is happening—sowing, planting, weeding and hoeing and the first of the harvests from overwintered crops and early spring crops too. It is a question of prioritising jobs generally, rather than trying to get it all done—you will only get stressed out if you think you can get it all done! We have a sowing calendar and we always try and stick pretty closely to these dates. With some crops, it doesn’t matter too much, but we end up doing a lot of successions of a lot of crops to try and keep continuity of harvest of things like beetroot, chard, kale, spring onions, salad leaves, annual herbs, radish, carrots and many more. Other crops sowing time is critical, and if they are sown at the wrong time of the year they will just go to seed really quickly (for example brassica salads like rocket), they may not bulk up in time before the winter (for example chicory – we don’t sow any later than the first week of July, but if you sow them too early they may bolt!), or they may coincide with certain pests—like flea beetle for brassicas from Spring—late Summer, or carrot root fly which can sometimes be missed if the carrots are sown early June and harvested before autumn.

We aim to have all of our tender summer polytunnel crops planted by the beginning of May, this includes climbing french beans, peppers, tomatoes and cucumbers. This year we were lucky to get a week of wet weather at the end of April which meant that we could focus on the tunnel changeover, from overwintered salads and herbs to the summer fruiting crops. Meanwhile, outside throughout April there were plantings of beets, chard, lettuce and other salad leaves, spring onions, shallots, early brassicas—kale, spring cabbage, kohl rabi, mangetout, broad beans, peashoots, turnips and radish and carrot sowings. The courgettes will be going in at the very beginning of May, as could squash and corn, but fleece will be needed to keep the wind off and keep any late frosts off (should be safe by mid-end of May).

It is a great time of year to be a vegetable grower—and with the rains at the end of a very dry April (after a very wet winter!) everything is looking very lush and growing well. The main pest that we have had to deal with this year is the leatherjacket—the larvae of the daddy long leg or crane fly. The adults lay their eggs from August to October, and wet conditions at that time of year leads to a high success rate of the eggs hatching (which is what happened last autumn). The larvae eat the roots of many plants, and even snip off plants at their base. They are difficult to control organically, though nematodes can be used (but are more effective when applied in the autumn. Otherwise, it is a case of checking under new plantings and picking them out, which is pretty laborious but has to be done if you want to save your veg!

So, the big priorities for May are making sure you have all of your seed sowing in order and getting done—including successions of things like salads, then making sure everything is getting planted, and finally making sure all of your new plantings are being hoed and weeded…not too much!

WHAT TO SOW THIS MONTH: kale, forced chicory, carrots, beetroot, chard, successions of lettuce and other salad leaves (not mustards and rocket—these will bolt too quickly now and get flea beetle), autumn cabbage, successions of basil, dill and coriander, early chicory—palla rossa and treviso types, cucumbers (for second succession), french and runner beans, courgettes, squash and sweetcorn if not already sown.

WHAT TO PLANT THIS MONTH:

OUTSIDE: salads, spring onions, beetroot, chard, shallots and onions from seed, courgettes, squash, corn, kale, last direct-sown radish early in the month, french and runner beans

INSIDE: If not already done—tomatoes, peppers, aubergines, cucumbers, chillies, indoor french beans, basil

OTHER IMPORTANT TASKS THIS MONTH: Keep on top of the seed sowing, but don’t sow too much of anything—think about sowing successionally. Keep on top of hoeing and weeding—ideally hoe when the weeds are just starting to come up on a dry, sunny, breezy day.

For more information about our veg bag delivery scheme go to trillfarmgarden.co.uk/boxscheme.html

We have a few veg plants available for sale at the moment – so if anyone needs any chard, beetroot, salads, beans, courgettes, squash and much more contact us by emailing ashley@trillfarm.co.uk”

Look on the Bright Side

Like most of you, I feel like I’m living in a sort of suspended animation. I certainly have no idea what day of the week it is since today is much the same as yesterday and the day before. Weekends used to provide a finite focus for the rest of the week—things to look forward to like going to the movies on Friday evening, a party with friends on the Saturday and maybe a roast Sunday lunch with the family, but all days are now the same. Looking back, I find that whatever used to be normal, now seems completely unreal. How quickly we adapt as humans!

When things get back to the way they used to be (as one day they surely will), I am probably going to have to re-learn how to shake hands without flinching. If anybody moves closer than six feet to me, it feels like common assault. Some days it’s a bit like living in a late-night science fiction movie where some awful disaster has overtaken the globe and I’m the only human left alive.

However, despite all the undoubted gloom and inconvenience of being locked-down and the endless daily drip-feed of virus statistics, there are some positive things about being in locked-down isolation. Just make sure you don’t keep watching the news each day because that’s enough to turn you into a gibbering heap of nerves. I find myself following the daily death statistics as if they were football results.

Noise: Or rather, the lack of it. There’s virtually no engine noise, no brake screeching and certainly no thunderous roar of motorbikes racing each other to death (sometimes literally) via Weymouth and back along the B3157 coast road. Up high in the sky, it’s an unbroken swathe of blue—no white contrails marking the transit of yet more holidaymakers jetting exhaustedly to far off Marmaris, Marrakesh or Magaluf. I can hear the occasional combine in the fields, but mostly it’s bird song and the buzzing of bees. My ears (long accustomed to the pleasurable thunder of Jimi Hendrix or Aerosmith at full blast) can finally be awoken by the soft shrill of sparrows arguing noisily in the bush next to my bedroom or the glorious blackbird song from the garden. This is good.

Money: As I’m already retired, there’s no great drop in income and no guilt at not earning my hourly pay. And, since we don’t have small children living with us which might threaten peace and sanity, my outgoings are less than normal. Actually, very greatly less! With no restaurants or cafés open and no coffee bars or pubs to tempt me out for a drink or a meal with mates, I have saved several hundreds of pounds this last month. Nor can I pop down the shops and pick up a spare pair of socks or a new tie—neither of which do I really need—and I can’t poke about looking for bargains in our local Saturday market. Do I miss going out and doing non-essential stuff? No, I can’t say that I do. I miss the people, but I don’t really miss picking up a second-hand light blue pie dish which would probably sit at the back of the cupboard until I gave it to a charity shop in two years’ time.

Keeping in touch: I’m most grateful for new technology and the rise of WhatsApp and Zoom. I make a point of calling, talking to and—now—even seeing my children and grandchildren, my sisters and my favourite cousins on a regular basis. OK, so I see them only on a little screen, but it’s great! I swear I never did it this much before. Back in whatever we consider to be normal times, I would often put it off and say I’d call my cousin Harry tomorrow. But now, the sense of isolation has made even tenuous family links seem so much more important. I could say for sure that the act of being ‘locked down’ has made me closer to my family, which is a bit weird but true. Distance makes the heart grow fonder etc.

Learning new stuff: With all this extra time on hand, I could be learning Spanish, studying art and how to paint properly, re-learning how to play jazz piano or even starting to write my memoirs. But you know I probably won’t. The thought is there and so is the attraction of learning a new skill, but I know I won’t be doing anything that constructive. I’ll continue thinking about doing it which will give me a positive feeling all day, but I probably won’t actually do anything except (hopefully) finish reading the whole of War and Peace. This is something I’ve always wanted to do, but again possibly never will…. I’ll get to the bit where Rostov is involved in the Battle of Austerlitz, and wonder if Prince Andrei’s wound will be terminal. I got here about five years ago at page one hundred and something. If my forced isolation lasts another couple of months, I might get to page 300 out of 1,500. Don’t worry. That won’t happen because they’ll have to start football again by mid-summer, so the clubs can afford to keep paying their multi thousand-a-week prima-donnas. The nation’s virus statistics help put that into its proper perspective.

The Mayflower

You may know this as the name of the ship which took many of the Pilgrim Fathers to the New World in 1620. If we did not have the present national emergency, no doubt we should have many references to the Mayflower in the next few months and Plymouth would be celebrating.

The Mayflower sailed from Southampton in August 1620 and then put into Plymouth for repairs before setting off on the journey. It ended up in New England on the coast of what became Massachusetts, but had expected to land in Virginia. So why did they undertake this hazardous journey 400 years ago?

The reason goes back over several hundred years, perhaps beginning with John Wyclif who lived in Oxford in the 1300’s and questioned papal authority. Then Desiderius Erasmus, a Dutchman who visited Oxford and Cambridge before his death in 1536. He was a Protestant and wished to reduce the power of the clergy. Shortly after, Martin Luther, who influenced people to doubt medieval ideas of salvation and of priests being paid for praying for the souls of the dead and for selling indulgences. He possibly inspired the Reformation in Western Europe in the 16th century after years of catholicism.

Then came the reign of Henry VIII who so pleased the Pope that he made him Defender of the Faith until Henry wished to divorce his Queen to marry Ann Boleyn. When the Pope refused Henry made himself Head of the Church of England and started to reduce the power of the monasteries and take their wealth. Henry was still effectively a Catholic, but his son Edward was a Protestant and went further than his father in overturning the monasteries. On his death in 1553 his sister Mary tried to return the country to catholicism and commenced burning Protestants. Queen Elizabeth 1 was protestant but her successor James 1 married a French Catholic.

All these changes and fears of religious persecution convinced some Protestants, some known as Separatists, that they should leave England initially for Holland and later for the New World where they could make a new start and worship God in their own way. England had increased in population, but the poor were getting poorer and the promise of their own land in the New World to settle on and grow crops was very attractive. The Mayflower migrants have become known as the Pilgrim Fathers and said to be the first settlers of the New World. We now know that there were others before them.

According to Cecil Cullingford in A History of Dorset, Sir Walter Erle of Charborough Park, later MP for Weymouth, helped to set up the Dorchester Company in 1623/4 with a view to establishing a base in New England to raise corn and meat for merchants in the cod fishing and fur trade. The Rev John White, rector of Holy Trinity and St Peter’s in Dorchester had helped the poor and homeless locally, then took a leading part in organising migration of Dorset Puritans to Massachusetts who wished to have freedom of worship without interference from bishops or government. Most of the leading Dorset Puritans were shareholders in the Dorchester Company.

A ship, the Fellowship, took 13 Dorset men to near Cape Ann north of Boston and later cattle were shipped out. In 1628 John Endecott was chosen by Rev John White to supervise the colony. With his wife and about twenty emigrants he sailed in the Abingale from Weymouth. In the following year three more ships sailed from Weymouth with emigrants to cross the Atlantic. In 1630 the town of Dorchester was established on the outskirts of Boston, Massachusetts. The largest group of emigrants under John Winthrop was in 1630. Another ship, the Mary and John sailed four times from 1607 to 1633 with different Masters, George Popham, Robert Davies, Christopher Jones and Robert Sayers, although I have not been able to verify this list. The Mary and John was at one stage owned by Roger Ludlow who assisted with the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Probably about 200 people migrated from Dorset to North America between 1620 and 1650, according to estimates by Richard Hindson in his short history of Bridport. He writes that migrants from the Bridport area included some from Symondsbury and two from Askerswell. One “Henry Way the Puritan”of Bridport sailed from Plymouth on 20th March 1630 with his wife Elizabeth and five children, ranging from 22 to 6 years old. They landed at Nantucket on the 30th of May 1630 and settled in Dorchester, Massachusetts.

In 1995 Mr E W Street from Lyme Regis gave a talk to Bridport History Society entitled The Mary and John, ship to the New World and introduced a “New World Tapestry” created of 24 frames. This was to be housed in Coldharbour Hall at Cullompten with a commentary in several languages. The tapestry is larger than the Bayeux tapestry. Panels were produced in Plymouth (2), Exeter, Tiverton and Lyme Regis among many towns. The Lyme Regis panel, 11 ft by 4 ft, contained 1.5 million stitches and included 11 flowers taken to, or brought back from America, Rocket, Snowdrop, Pasque Flower, Garlic Mustard, Hyssop, Wolfsban, Cranesbill, Dead Nettle, Elm, Leopardsbane and Fritillary. The panel also included 11 coats of arms relating to families which had migrated to the colony. The last stitch was added in Connecticut, USA. A total of 45 pictures was incorporated telling the story of the travellers to the new world of Massachusetts.

This January at the local Family History meeting in Loders our friend and colleague, the historian Jane Ferentzi Sheppard discussed the Pilgrim Fathers and introduced two ladies who are both descended from the original Pilgrim Fathers, Carrie Southwell and Donna Heys. This talk was to be repeated at Bridport History Society this May and we hope will be given as soon as this present emergency is over.

Both ladies added to Jane’s talk. Carrie said her forefather, William Banister from Nottinghamshire sailed from Southampton and Plymouth to land in September 1620 and they were welcomed by local people. Some descendants of the local original Indians who met the Mayflower are still living in the area. The Pilgrims hunted and foraged for food and then built houses for themselves. A thanksgiving service was held after a year. Donna grew up in the USA and said that of the 102 pilgrims who arrived only 52 survived the first winter and now there are 35 million descendants in the USA. A William Mullins left Dorking, Surrey, for the Plymouth Colony in the Mayflower and his old house still survives in Dorking it has been said.

Bridport History Society will not be meeting again until the present emergency is over when we shall advise dates and content of meetings. Good luck and good health to all.

Cecil Amor, Hon President of Bridport History Society.

Crisis and Opportunity

Some people can live easily with their own company; some find it more difficult. Some, naturally gregarious or communicative, find it virtually impossible. But when there isn’t a great deal of choice in the matter, as is the case with the extraordinary circumstances in which we now find ourselves, perhaps the very restrictions can be fashioned into new opportunities. People who have always had an idea that, given the chance, they could write something which those who decide these things would be willing to publish, have just had a perfect opportunity dropped in their lap.

Aspiring writers will often turn to creative writing courses, though many of these will struggle to continue in the present situation, except by correspondence. Magazines aimed at would-be writers are full of advertisements offering self-publishing and writing critiques. As the options are weighed up and the sums calculated, what are the chances of getting into print without straining the bank balance with courses or self-publishing projects?

In 2003, I had never published any ‘creative writing’ at all. During a career in teaching and educational research, my research reports and research-based articles had been published in the educational press, but no fiction or poetry with my name on it had ever appeared in literary magazines.

When retirement circumstances allowed me to leave education in my mid-fifties, I felt the break needed to be a clean one. I’d always told myself that the creative writing impulse which had produced a few juvenilia novels and some scripts and poems for the kids would finally come into its own as soon as a real opportunity arose. Now the time had come for me to call my own bluff.

Firstly, I had to decide on the need or otherwise for a creative writing course. The resources were available if necessary, but I felt I needed to take a long and careful look at what was on offer before risking any serious amounts of money—and hope.

Secondly, I knew something of what many editors and publishers will tell you are the ever-present plagues of their lives. They include people who haven’t actually read any short fiction or poetry for decades submitting work imitating long dead authors; people who have never published anything sending in manuscripts and expecting immediate success, and people sending in stories and poems to magazines and e-zines which make it obvious that they have yet to read an edition of the magazine.

I did enough reading and research to become aware of the realities of approaching agents and publishers. Even writers with lists of published works don’t automatically get into print. Sending work to publishers or agents when you have never published anything is, to be frank, a waste of everyone’s time. Even in the case of the smaller print magazines and e-zines, submissions from unpublished authors are up against it.

After three years, I hadn’t drawn a complete blank; four poems and two short stories had made it into small magazines. But I’d also accumulated a collection of rejection letters and e-mails, most of which were no help at all. I felt that the passing years forbade me too much time; something needed to happen to accelerate the process.

I chose competitions rather than courses. Competitive writing is, in the last analysis, the acid test; if a writer does have a spark of genuine ability, and the material is good, results will come. If they just don’t, then knowing where you stand, cruel as it may be, is better than lavishing energy, expectation and money on what is probably a dead-end alley. Of course, the courses route is always available to people who have time and money enough and who genuinely believe that courses will enable them to reach the required standard.

Even for writing competitions, a little scam-awareness is necessary. Most legitimate competitions will charge a modest entry fee of a few pounds, and it is clear from their prize structure where most of the money goes. If the entry fee seems hefty and the prize structure modest or non-existent, the competition is best avoided, and likewise if there is no explanation of who is judging, how the judging is taking place and when and how the results will be made available. In my experience, the longer a competition has been going and the more precisely defined its structure, the greater the chance that it is legitimate.

Following on from four published collections of short stories, I published my first novel, Howell Grange, in October 2019. I didn’t, from the start, set out to make any significant amount of money from writing, and anyone who does aim to do so is likely to find the route difficult. But my first two collections consisted entirely of stories which had won placings, commendations or listings in short fiction competitions, and my first poetry collection had a large proportion of poems gaining similar results. There is a lot of stimulation, satisfaction and challenge to be had in creative writing, and good luck and best wishes to anyone who decides to have a crack at it.

Bruce Harris’s awards list includes prizes, commendations or listings in competitions organised by Momaya Press, GRIST Magazine, Retreat West, Writer’s Bureau (twice); Grace Dieu Writers’ Circle (five times); Cinnamon Press, Artificium (twice), Biscuit Publishing, Yeovil Prize, Milton Keynes Speakeasy (three times), Exeter Writers, Fylde Writers, First Writer, Brighton Writers (three times), Exeter Story Prize, Ifanca Helene James Competition, HISSAC Competition, Ink Tears, Wells Literary Festival, Wirral Festival of Firsts, New Writer, Segora (twice), Sentinel Quarterly, Swale Life, Rubery Short Story Competition, Mearns Writers, Erewash Writers, Nantwich Festival, Bedford Writing Competition (twice), Havant Literary Festival, Earlyworks Press, Southport Writers’ Circle (twice), West Sussex Writers, Lichfield Writers’ Circle, Cheer Reader (three times), TLC Creative, 3into1 Short Story Competition, Waterloo Commemoration Short Story Competition, Meridian, Homestart Bridgwater Competition, Five Stop Story (three times), JB Writers’ Bureau, Red Line (three times), Bridport Prize shortlist (twice) and Bristol Prize longlist. He has also been extensively published in magazines and e-zines.

www.bruceleonardharris.com

See links section for details of writing competitions.

Howell Grange by Bruce Harris, a story of a Northern mine-owning family set in the mid-nineteenth century, was published by the Book Guild on October 28th 2019.

It is available for ordering at:

The Book Guild

Foyles

Waterstones

Booktopia

W H Smith

UpFront 05/20

In the film Cast Away, Chuck Noland, a systems engineer for the delivery firm FedEx is stranded alone on a desert island. Played by Tom Hanks, Noland develops a relationship with a volleyball which he calls Wilson. Since Noland is stranded alone for years, Wilson becomes quite important to him and there is an emotional scene where the two become separated. Since the implementation of COVID-19 restrictions, there have been endless stories of families bonding, families fighting, friends reuniting and couples discovering true love – or not. But living alone in isolation is a strange thing. Having ‘unplugged’ my old friend the listening speaker ‘Alexa’ last year, I decided to reinstate her during lockdown. We have now rekindled our relationship and she happily brings me music as well as radio stations and news from around the world. However, she really came into her own recently when I had problems with a neighbour—a scratchy neighbour. This particular creature had a habit of getting busy at unsociable times, often when most of us like to sleep. My little friend had decided to build a home somewhere in the walls of the caravan. This would be fine if he or she was prepared to work the same hours as me, but no, it had to be during the night. So I recruited Alexa and asked her to play some tunes that might distract my friend from their nocturnal excavation. Thus began a journey into songs I haven’t heard for years. In a Gadda Da Vida by Iron Butterfly; Hocus Pocus by the Dutch band Focus; Moving to Montana by Frank Zappa. I was on a mission to find songs that might be too much for my little friend to compete with. I even tried a bit of Taiko drumming. But it was all to no avail. I think ‘scratchy’ quite liked it. So I changed tack and decided to instruct Alexa to play some animal noises. I was sure that the sound of a cat would do the trick, and when that didn’t work I moved up the scale, experimenting with a tiger, a lion and then a panther—now that is scary. Before long I found that listening to recordings of different animal noises distracted me completely from my initial goal. Now, trying out new animal sounds has become a daily diversion. I don’t often hear my little friend anymore though—he or she may well have moved to a quieter part of the jungle. However, Wilson is now being difficult. He doesn’t like it one bit and says I might be going nuts.

Sasha Constable

‘Reflecting on one’s life as we all endure this period of isolation feels quite poignant. It’s a challenging time for everyone but artists tend to work alone and I am thankful to have a creative outlet to occupy my mind and time.

Life seems to have come full circle lately. I was born in a cottage hospital near Glastonbury and moved to Norton-sub-Hamdon when I was six where we shared a large house with my paternal grandmother. It was an idyllic childhood, my brother and I were left to play outside in our beautiful garden, build dens in my father’s overgrown asparagus bed or roam around the woods on Ham Hill.

My father was a professional artist and we knew not to disturb him when he was in his studio. He was also a very productive gardener and grew an abundance of fruit and veg the success of which he maintained was due to the extra nutrients that came from the neighbouring churchyard. Dad’s variety of produce and my mother’s cooking skills gave us a healthy start in life. Her resourcefulness also filled some of the gaps left by his low income. Whilst his imagination got lost in the layers of a hedgerow my mother introduced us to foraging the delights they have to offer. It was a very 70’s model of self-sufficiency.

My father passed on his love of nature and collecting random quirky, captivating objects. Skulls featured heavily and picking up roadkill and driving home with a dead fox or badger on the bonnet of the car was quite normal. Digging up a buried animal to reveal a newly picked clean skeleton was always a thrill. The natural world and his own experiences fuelled his vivid imagination and I, in turn, absorbed both of these as foundations for my own inspiration.

At school, my time was largely split between the art department and the sports field. In the run-up to my A levels I had a week’s work experience with a picture restorer in London which was fascinating. It gave me an invaluable insight into the complexities of different artists’ techniques. I spent a great deal of time spitting on to cotton buds using saliva to clean the surface dirt on various oil paintings by some of the modern masters.

Having been accepted on Kingston Polytechnic’s (now University) art foundation course I moved to London, aged just 17. One of the last projects during my foundation year was sculpture. Finally, I felt as though I had found my calling. At the same time I became absorbed in relief print-making, satisfying a craving to create more complex two-dimensional images in a medium that still involved something of sculpture’s physicality. It was one of my large woodcuts of 3 pig carcasses hanging at Smithfield market that was to change my life.

In New York early in the summer of 1989 there was an exhibition of 6 generations of Constables, an intimate family exhibition. John Constable is my great-great-great grandfather; each generation since JC has produced at least one artist. My woodcut was included in the exhibition and although it wasn’t for sale, an art collector made me an offer of $2000. That unexpected sale enabled me to travel in Thailand for 3 months, a period that was incredibly important as I developed a deep love for Asia and exploration that has both informed and enriched my life.

Back in the UK I began a 3-year sculpture degree at Wimbledon School of Art, a small institution with an emphasis on skills. In the first year we covered many sculptural techniques; modeling, welding, construction, carving and casting, however it was still stone that resonated most with me.

After completing my degree an old school friend and I painted our first mural together in Germany. When we finished I spent a few months traveling around the country studying various print collections, particularly the German Expressionists. On my return my friend and I painted another large-scale mural at Brympton D’Evercy, a stately home near Yeovil.

Making a living as a young artist was a struggle so in my mid-twenties I embarked on a PGCE course to teach art and design at secondary school level. Teaching is another invaluable skill that has helped shape my life. However, I decided that full-time teaching was not for me and in 1997 I decided to focus on stone again and travelled to India to study its magnificent temples, feats of sculpture and engineering.

Then in 2000 I met the director of the World Monuments Fund (WMF) in Cambodia and was invited to visit for 3 weeks as an artist in residence. Those 3 weeks turned in to 17 and a half years meaning in all I’ve lived more than half of my adult life in Asia. My first experience of the temples in the Angkor Park was 2 weeks after arriving in Cambodia. The World Monuments Fund together with the Grand Hotel D’Angkor had organized a VIP function at the East Gapora of Preah Khan temple. Travelling out to Preah Khan in the back of the WMF pickup truck and then walking through the temple after dark, the corridors lit by candlelight, was utterly magical. I was smitten.

I fell deeply in love with Cambodia and its extremities, its culture, landscape and people. It was wild and tranquil, beautiful but harsh, exciting, sometimes disturbing. So many emotions, so much history to grapple with in how a country that has been constantly torn apart can be rebuilt through time. When I arrived in the town of Siem Reap in 2000 the expat community was small, a mix of nationalities working in different sectors; NGO’s, UN, hospitality, business or general wanderer. My time was divided between working in the Angkor Park, days out on the Tonle Sap lake, dirt bike trips, adventures to remote temples and nights spent in the 3 bars the town had to offer.

My work with WMF led me to the Fine Art department at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh where they were keen for me to teach. In 2001 I set up a relief print-making workshop. It was a huge success and of great significance as I realized I could use both my artistic and teaching skills and make an idea for a project happen through fundraising, coordinating and curating. The following years have been filled with a mix of them all.

One of the ideas that became a reality was The Peace Art Project Cambodia (PAPC) which I co-founded in 2003. PAPC was a project turning weapons of war into symbols of peace and was to be another important moment in my life. A key experience as it was the first large-scale art project that raised awareness about a serious global issue; with PAPC it was the proliferation of small arms in conflict and post-conflict countries. Other large-scale projects followed every few years addressing different issues. Curating and promoting artistic talent became a focus; it was an exciting time where there was a developing contemporary art scene with some beautifully passionate, talented, clever artists, in a country where ninety percent of Cambodian creatives had died under the Khmer Rouge. In this post-conflict environment education was key to the country’s development. Being a teacher in Cambodia was a pure joy, feeding young minds hungry to learn and with no discipline problems whatsoever…

Quite unexpectedly I also became the British Embassy to Cambodia’s Honorary Consul in Siem Reap. When I started in 2008 there was a huge rise in British nationals visiting Cambodia so the FCO deemed an Hon Con a necessary role. I was a frequent visitor to the hospitals, the police station and jail assisting British nationals and citizens from the numerous other countries that the UK covered with assistance abroad.

My son was born in Bangkok in 2013. Around the same time my father was diagnosed with vascular dementia. Over the following two years my son and I split our lives between Cambodia and the UK helping my mother care for my father as he rapidly succumbed to dementia’s debilitating effects. Dad died in September 2015. His passing was probably the catalyst for deciding it was time to relocate back to the UK. Now we are settled once more in the West Country having swapped the temples of Angkor for the Cerne Giant, the Jurassic coast and Dorset’s other wonders. It feels like the wheel of life has turned and I’m back where I began and although Cambodia changed my direction, ultimately it has led me back to my homeland.’

People at Work Kim Biss

A smile will always greet you from behind the counter of Naturalife in Bridport, and more often than not it will belong to Kim Biss. She welcomes all customers, new and regulars alike with a calm and bright approach, ready to dispense her wisdom and advice to all. Founder of the health food and supplement shop, Kim is celebrating 20 years since it opened, offering carefully curated products to help her customers live a natural life.

Kim started dispensing from behind a counter when she left school, working for Boots when she was living in the Midlands. When she moved to Merriott with her young family, Kim did a professional catering course at Yeovil College. She was introduced to natural and health aligned products when she took on a job at Holland & Barrett in Yeovil, qualifying as a product advisor. However, the branch had to close and she became redundant. This provided Kim with the opportunity, and push, towards opening up her own health shop in a little unit in Crewkerne, which she’d spotted some months previously. From there another shop was opened in Dorchester, which Kim also ran for a number of years, before a fresh new start was in order.

Always taken with Bridport, Kim decided to open Naturalife in South Street. She relocated and settled with her husband Martin round the corner from the shop. Loving the variety on her doorstep, Kim is ideally placed to pursue her love of food, ignited when she did the catering course and enjoys eating out regularly. She also has a love of glitter, so you may see the odd sustainable card for sale in the shop, sparkling in the light.

Hannah, Kim’s daughter-in-law is also now an integral part of the business. She also helps run the shop and goes to trade events with Kim. Working hard to get to where she is now, Kim is grateful that she can carry on doing what she loves, in the knowledge that the business will continue, indeed already is, in safe family hands.